The dominance of Spain in western European affairs and the Spanish tactical system in sixteenth-century warfare required its enemies to seek new ways to meet and defeat the tercio on the battlefield. One of Spain’s most capable adversaries was a young nobleman from the Netherlands, Maurice of Nassau (1567–1625), who gained prominence in that country’s war of liberation against the Spanish. The second son of William the Silent of Orange, Maurice was granted the title of prince of Orange after his father’s assassination in 1584, and rose to the position of admiral general and captain general of five provinces within the United Provinces. In this capacity Maurice instituted a number of military reforms, including the founding of the first military academy to furnish his army with trained officers, emphasizing drill and discipline. In fact, the reintroduction of drill into the Dutch army was an essential element of the Orangeist reforms and a basic contribution to the modern military system.

Maurice recognized the successes of the Spanish tercio in recent decades and endeavoured to create a means to defeat the Spanish battle square. Like other commanders of his day, the prince of Orange was inspired by the classical period, gleaning ideas from authors such as Leo, Aelian and Vegetius. To defeat the tercio, he abandoned the battle square and adopted a linear formation on the Roman model. In doing so, he maximized firepower through the elongation of formations and rapidity of loading. Maurice’s reforms utilized familiar hallmarks from the classical period, specifically intelligent leadership, unquestioning obedience, loyalty to the unit, and improvements in tactical deployment and mobility. Because of manpower shortages and financial restraints, he was forced to do more with less. To meet muster, foreign mercenaries (mostly French, German, English and Scottish) were hired and paid well, giving the Dutch army ‘a proficiency, discipline, cohesion, and maneuverability unknown in the West since Roman times’.

Maurice also reduced the size of the standard tactical formation to battalions of 550 men consisting of heavy infantry pikemen and light infantry arquebusiers. Originally using a heavy infantry formation ten men deep, Maurice finally deployed his pikemen five deep with a frontage of fifty men. This shallow array meant more Dutch pikemen could face the enemy, and none found themselves out of action in the centre of a densely packed battle square. To each side of his heavy infantry, the prince of Orange placed his light infantry arquebusiers, arranging them four abreast and ten deep. He also included in this tactical array about sixty arquebusiers as light infantry skirmishers. He arrayed the battalion in three lines, allowing commanders to commit reserves of balanced infantry units when and where circumstances warranted.

Like the Romans, Maurice emphasized drill and discipline above all other martial virtues. He compelled his arquebusiers to practise motions required to load and fire their matchlocks, while drilling his pikemen in the proper application of their polearms when marching and in battle. Although this kind of instruction was not entirely new, what was new to the early modern period was his emphasis on unit cohesion and simultaneous drill. Since his handgunners were trained to move in unison and in rhythm, all were ready to fire their weapons at the same time. This made firing volleys easier, creating a greater shock effect on enemy ranks.

Maurice also emphasized marching in cadence to precise commands, giving his soldiers the ability to move in prescribed patterns, forward or back, left or right, shifting from column to line and back again. But perhaps the most important manoeuvre instituted by the prince was the refinement of the Spanish countermarch. In the Dutch countermarch, the first rank of arquebusiers and musketeers fired their weapons, then wheeled and marched between the files of the men standing behind them to the rear, reloading their weapons in unison to the precise commands of an officer. Meanwhile, the second rank discharged their weapons and repeated the manoeuvre until all ten ranks had rotated through and the first rank was ready again to fire. With practice, the countermarch allowed the Dutch battalion to continuously fire at enemy formations, giving an adversary no time to recover from the impact of one volley before another volley hit home. One historian rates the increase in firepower in the new Dutch battalion on the order of 100 per cent.

Dutch battalions were each capable of better independent articulation on the battlefield because of their better manoeuvrability, and a high proportion of officers and non-commissioned officers to enlisted men. Maurice placed his battalions in a chequerboard formation reminiscent of how the Romans deployed their legions. But linear formations, whether classical or early modern, suffered from an increased vulnerability on their flanks. To solve this problem, Maurice utilized cavalry on the wings to protect his infantry’s flank in the same way the Macedonians and Romans had done 2,000 years earlier.

The contributions of the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus (r. 1611–1632) to modern combined-arms warfare are manifold and represent a watershed between the traditional heavy cavalry and polearm-based tactical systems of the late Middle Ages and the new articulated gunpowder-based linear formations that would dominate the battlefields of the west until the nineteenth century. Gustavus’s significance lies in his successes as a battle captain utilizing this new tactical system in his campaigns against the Poles and Russians, and in the Swedish phase of the Thirty Years War (Map 7.3). The wholesale adoption of the Dutch tactical system by European armies after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 is eloquent testimony to the power of the ‘Lion of the North’s’ tactical synthesis.

The cornerstone of Gustavus’s tactical innovations came from lessons learned by the Dutch in their war of liberation against the Spanish a generation before. When the young Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus adopted the Dutch tactical system, he modified it to maximize shot over shock. He changed the battalion configuration, arranging his pikemen six deep and thirty-six across, with ninety-six arquebusiers on each side in six ranks. Furthermore, he substituted the heavy arquebus for a lighter matchlock musket and gave each of his soldiers paper cartridges containing measured amounts of powder. He then put these new technological advances to good use by instituting the tactic of volley fire.

Volley fire consisted of all six ranks of musketeers loading their weapons, then reducing the six ranks to three by filling the intervals between the men ahead. The first rank knelt, the second stooped and the third stood, and all three fired simultaneously. By this means, Gustavus used rotation offensively, with the back three ranks moving forward through stationary reloaders. The Swedes became so skilled at this manoeuvre that their infantry battalions could discharge two volleys per minute. Though a proponent of light infantry, Gustavus did not dispense with offensive shock tactics, and his pikemen continued to advance even during the countermarch, contributing to the final impact. But at close range, the rolling fire of the countermarch was replaced by a single devastating volley fired simultaneously by all three ranks of musketeers.

To support his light and heavy infantry, Gustavus changed cavalry doctrine, abolishing the widely used tactic of the caracole in favour of arming his cavalry with sabre and committing them against infantry when shock action seemed likely to succeed. He also created the world’s first dragoons, arming them with carbines, wheel lock pistols and, later, with sabres, effectively fusing heavy and light cavalry into one weapon system. The young king’s fascination for shot over shock can also be seen in his integration of small, horse-pulled artillery into battalions. Firing cannonball, grape or canister shot, these four-pounders were light enough to be manoeuvred with the battalion on the battlefield, concentrating firepower where it was needed most.

Map 7.3 The Thirty Years War.

Gustavus Adolphus, a Protestant king, entered the Thirty Years War in the summer of 1630. The war had begun twelve years earlier when a Calvinist rebellion in Bohemia in 1618 led to imperial repression by the Habsburg ruler and holy Roman emperor Ferdinand II, sparking a war between Catholics and Protestants across Germany. Denmark intervened on the side of German Protestant states in 1626, but by 1629 imperial forces had defeated the Danes and pushed imperial power to the shores of the Baltic Sea. Because the holy Roman emperor did not have a large army himself, imperial forces were drawn from the levies of greater lords within the empire, men such as the elector Albrecht von Wallenstein, or from Spanish troops provided by his royal cousin King Philip IV.

With the Swedish king’s arrival in Peenemünde on 4 July 1630, the momentum of war began to switch to the anti-imperial forces. Over the next year, Gustavus’s forces overran the Germanic Baltic states of Pomerania and Mecklenberg, then pushed south into Brandenburg in April 1631. The brutal sacking of Protestant Magdeburg in May of that year by the seasoned commander Jean ‘t Serclaes, count of Tilly, and his imperial forces pushed the region of Brandenburg into Gustavus’s camp. After securing contributions and the right to recruit soldiers in Brandenburg, the Swedes moved south into Saxony to forage for supplies and meet reinforcements from Italy. Recognizing the need to defeat the Swedish invasion, Tilly turned north and marched to meet the anti-imperial forces.

The initial meeting took place in late July 1631, but Gustavus’s strongly fortified position at Werben in a bend in the Elbe River discouraged Tilly from fighting. The latter skirmished, fired his cannon and withdrew 20 miles from the battlefield. In late August he seized the initiative, marching south and laying waste to Saxony in an attempt to discourage the elector of Saxony from joining the Swedes. Gustavus quickly marched to join his army with that of the elector and move against Tilly. In mid-September, the count’s army of 35,000 men offered battle on level ground between the little villages of Breitenfeld and Stenburg, a few miles north-east of Leipzig. After joining the elector of Saxony on the march, Gustavus arrived the night before the battle, and ordered his newly combined army of 42,000 men to sleep in formation.

The Swedish king arrayed his two armies side by side, placing the elector’s army of some 17,000 on the left and his own 25,000 troops on the right. Subscribing to the modified Dutch linear tactical system reminiscent of the Romans, Gustavus formed his 500-man infantry battalions in two lines, placing a reserve of infantry and cavalry between the two, and a reserve of cavalry behind the second line. His allied Saxon army consisted of traditional battle squares protected by cavalry on each flank. Because the Swedish and Saxon hosts deployed as separate armies, the combined forces had cavalry in the centre as well as on the wings.

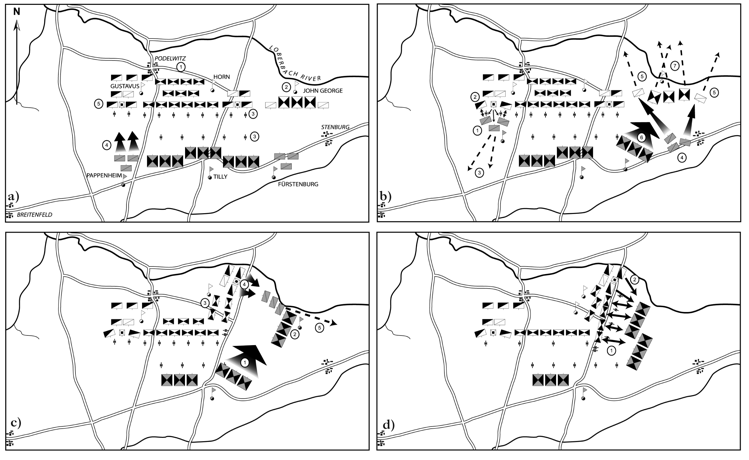

The battle of Breitenfeld began on the morning of 17 September 1631 when Gustavus ordered an attack and the Swedish and Saxon armies marched toward the count of Tilly’s already formed position (Map 7.4(a)). The imperialist army was arrayed in a traditional manner in 50 by 30 mantercios arranged in a group of three, with the centre square slightly forward of the other two. Outnumbered by perhaps 7,000 troops, Tilly was forced to spread out his army in one line to match the Swedish front. He had no reserve beyond some cavalry.

As the two sides closed, their artillery fired cannonballs through the opposing ranks. In an audacious move, Tilly took the offensive, ordering the commander of the imperial light cavalry reiters on his left, Count Pappenheim, to charge the Swedish cavalry on the right wing (Map 7.4(b)). Anticipating this attack, Gustavus placed additional heavy cavalry supported by light infantry musketeers to defend against the reiters. The Swedish cavalry held their ground and received the imperials’ pistol attacks, counter-attacking with their own musketeer volley fire and short sabre charges. Advancing seven times to repeat the caracole manoeuvre, the imperial light cavalry were unable to scatter the Swedish musketeers, instead being forced back by their heavy cavalry protectors. After defeating the seventh attack, Count Pappenheim ordered his imperial cavalry to withdraw from the field.

While Tilly’s cavalry unsuccessfully attacked the Swedish right wing, he ordered the battle square and cavalry on his right to attack the Saxons, keeping the remainder of his infantry in reserve. The imperial cavalry easily routed the Saxon horse, and the experienced Tilly, seeing an opportunity to push home a victory, ordered his centre square to cross the field obliquely and enter the fray against the Saxons (Map 7.4(c)). Demoralized and without cavalry support, the Saxon infantry broke and fled, pausing only to quickly loot their Swedish ally’s camp as they left.

With the rout of the Saxon army, Tilly had defeated 40 per cent of his enemy’s forces, and in doing so exposed Gustavus’s army to an attack against the flank of the remaining Swedish infantry formations. But as Tilly reordered his infantry in an attempt to roll up the Swedish flank, the Protestant king and his talented subordinate General Gustav Horn quickly formed the flexible and well-drilled infantry of the second line into a battle array to meet the imperial attempt to attack its flank. Completing the redeployment manoeuvre in only 15 minutes, the Swedish line faced the count’s infantry.

The next phase of the battle began with a cavalry engagement, with the Swedish cavalry on the king’s left driving off the remaining imperial cavalry. As the infantry closed, Gustavus’s new model army, with its six-rank-deep linear array and disciplined volley fire, began to have an impact on the enemy battle squares (Map 7.4(d)). The imperial arquebusiers and musketeers, fifty files wide and thirty ranks deep, used the countermarch to maintain a steady rate of fire, but these ranks withered under the concentration of volley fire and follow-up cavalry sabre charges and heavy infantry pike attacks.

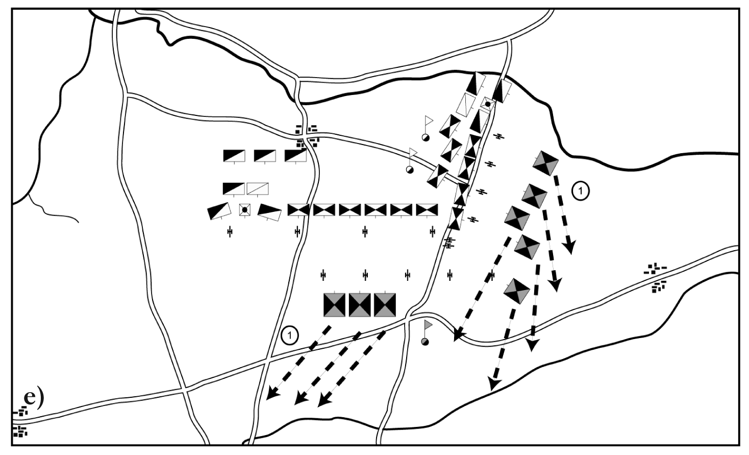

Map 7.4 The Battle of Breitenfeld, 1631. (a) Phase I: Gustavus Adolphus orders his Swedish army (1) and that of his ally, John George of Saxony (2), forward against the count of Tilly’s imperial army. The first shots of the engagement are fired by the opposing artillery (3) as the two sides close. Tilly opens the action, ordering Count Pappenheim’s light cavalry (4) to charge the Swedish horse on Gustavus’s right flank (5). (b) Phase II: The imperial reiters launch a series of caracoles against the Swedish heavy cavalry (1), which the Swedes answer with their own sabre charges supported by volley fire from the musketeers (2). Pappenheim finally orders the imperial horse to retreat (3). Meanwhile, the imperial cavalry on the right flank charge their Saxon opponents (4) and drive them from the field (5). The imperial infantry squares on Tilly’s right are on the move as well (6), and John George’s Saxons, left without cavalry support and facing Tilly’s oncoming infantry, break and flee from the field (7). (c) Phase III: Tilly orders his centre group of tercios to move obliquely to the right to reinforce the imperial success (1). The imperialists’ right-flank infantry re-forms and prepares to roll up the Swedish left (2), but Gustavus and General Gustav Horn quickly redeploy the second line to face this new threat (3). The Swedish cavalry charges Fürstenburg’s imperial horse (4), driving them from the field (5). (d) Phase IV: The imperial squares come under heavy fire from the Swedish light artillery and Gustavus’s linear infantry formations (1). The imperial troops return fire using the countermarch, but the Swedish volleys soon begin to overwhelm Tilly’s soldiers, who now come under attack from Swedish pikemen and charges from the Swedish heavy cavalry (2). (e) Phase V: The imperialist army is shattered by the combined effects of Swedish infantry, cavalry and artillery; Tilly orders what is left of his army to retreat (1).

Tilly’s infantry, exposed to artillery and infantry fire and cavalry attacks, took heavy casualties (Map 7.4(e)). Faced with the devastating fire of the excellent Swedish guns, easily manoeuvred on their lighter carriages, and his own captured imperial guns, Tilly ordered his troops to retreat. Imperial casualties were 7,600 killed, compared to 1,500 Swedes and 3,000 Saxons. Furthermore, the Swedes took an additional 6,000 imperial soldiers prisoner, though many of these men eventually enlisted in the Swedish forces. Tilly then retreated west over the Weser River, leaving Bohemia and the Main valley exposed to Saxon and Swedish advances.

The battle of Breitenfeld illustrated the dominance of shot over shock in infantry engagements in early modern warfare. The Swedish linear formation, with its broad front and volley tactic, allowed for a concentration of fire against the relatively narrow front of the imperial battle square, which, utilizing the countermarch, could return fire only one rank at a time. The battle also demonstrated the importance of combined-arms co-operation between linear arrayed infantry and their heavy cavalry comrades. Gustavus’s more innovative linear formation, only six ranks deep, was far more vulnerable to flank and rear attack than Tilly’s more traditional battle square tercios, with their all-round defence capabilities. The linear tactical system’s vulnerability placed a high premium on winning cavalry engagements. Short sabre charges assisted Gustavus’s infantry against Pappenheim’s caracole tactics at the beginning of the battle, and later vanquished the remainder of Tilly’s horse after the count had turned the Swedish flank. And as the early modern period wore on and the pike gradually disappeared in favour of linear infantry formations, the importance of cavalry increased on the battlefield.

After the defeat of imperial forces at Breitenfeld, many German Protestant princes rallied to the Swedish side. Gustavus advanced deeper south into Germany, taking Würzburg in October and Frankfurt in December 1631. In 1632 he planned to attack Bavaria and then conquer Austria. Count Tilly was killed trying unsuccessfully to stop the Protestant invasion of Bavaria, forcing Emperor Ferdinand II to reappoint a former general in the Thirty Years War, the Bohemian military commander Albrecht von Wallenstein, as overall general of the imperial army.

Wallenstein immediately threatened Saxony, forcing the Swedish king to return northwards and meet the threat to his newly acquired allied territory. What followed over the autumn of 1632 was a chess game of positional warfare, with neither side willing to attack its well-fortified opponent. At Alte Vista near Nuremberg, Gustavus was unable to drive Wallenstein’s forces from their heavily fortified position. Moving to the city of Naumberg, Gustavus dug in thoroughly and awaited an imperial attack. Wallenstein mistook the entrenchment for the Swedish king’s winter camp, and began to disperse his army for the season. With his own army evaporating from lack of supplies, the Swedish king decided to attack the weakened imperialist army at Lützen on 16 November 1632.

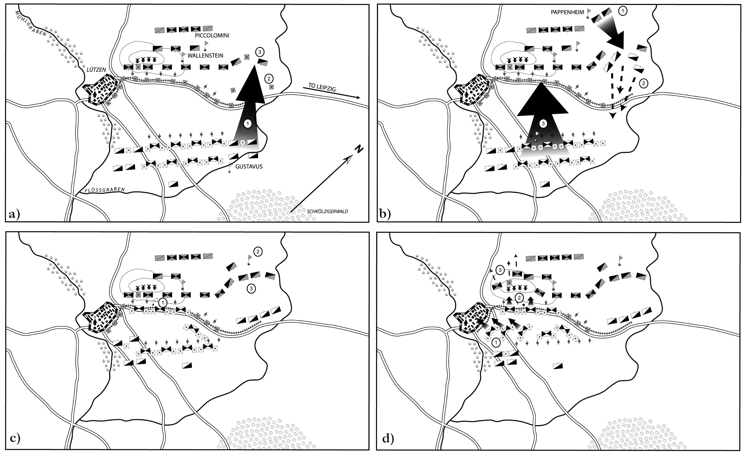

Gustavus reached Wallenstein’s position late in the afternoon the day before the battle with an army of about 19,000 men, of whom approximately one-third were cavalry. Imperial forces were about 16,000 strong, half being cavalry. Gustavus deployed his troops in two lines, ordering his mixed infantry in the centre and his cavalry, along with light infantry skirmishers, on the wings. He placed his field guns in the centre as a screen for his infantry. His strategy utilized his superiority in cavalry. The king placed his best cavalry on his right, planning to charge the imperial army’s open left flank and then roll up the enemy infantry’s flank and rear.

Recognizing the Swedish king was willing to offer battle, Wallenstein called back his lieutenant-general Count Pappenheim and his 3,000 cavalry from a nearby town, and dug in defensively behind a raised road. Wallenstein placed his right flank on the village of Lützen, arranging his artillery on a nearby rise where it could command the field below, and covered his left flank with a shallow stream. He ordered his men into a traditional formation, placing his infantry in the centre and cavalry on the wings. But he moved away from tactical orthodoxy by emulating his opponent and adopting smaller formations less than ten ranks deep, and arrayed them in two lines. He also ordered his cavalry to discard the caracole manoeuvre and copy the Swedish shock attack. Finally, he adopted a combined-arms approach to his defence, placing musketeers with his cavalry and some light guns with his infantry.

Preparing for the Swedish assault, Wallenstein deepened a ditch in front of his position and waited for Pappenheim’s reinforcements. Like the battle of Breitenfeld a year earlier, Gustavus arrayed his army the night before and planned to attack the imperialist forces first thing in the morning before the arrival of the count and his cavalry, an event that would even the forces.

But on the morning of the engagement, a fog enshrouded the battlefield, delaying the Swedish assault until midday (Map 7.5(a)). To open the battle Gustavus launched a cavalry assault against the imperial left and centre. But just as the Swedish cavalry had defeated the opposing horsemen, Count Pappenheim arrived and stopped the Swedes from running up the imperial flank (Map 7.5(b)). Moments after appearing on the field, Pappenheim was mortally wounded by a cannonball. In the centre, Gustavus himself led an infantry attack, pushing back the opposing musketeers. Though wounded by a shot in the arm, he was able to secure a ditch in front of Wallenstein’s position. Still, the imperial line held and Gustavus was shot two more times in the back and in the head, and died in the mêlée (Map 7.5(c)). Meanwhile, the Swedish cavalry continued to press on the imperial left, forcing Wallenstein to order the Italian commander Ottavio Piccolomini to replace the injured Pappenheim and repulse the Swedish cavalry attack. After having seven horses shot from under him, he was finally able to stabilize the situation there.

Map 7.5 The Battle of Lützen, 1632. (a) Phase I: Dense fog across the battlefield delays Gustavus’s attack against Wallenstein’s positions until midday. The Swedish king orders a cavalry charge (1) against the enemy’s left flank, scattering the screen of musketeers lining the ditch along the Leipzig– Lützen road (2), and threatening to roll up the imperialists’ line (3). (b) Phase II: Just as the Swedish cavalry gain the upper hand, Count Pappenheim arrives with cavalry reinforcements (1), stabilizing the situation and repulsing Gustavus’s horsemen (2), though the count is mortally wounded by a cannonball shortly after arriving on the field. In the centre, Gustavus personally leads an infantry attack and gains the ditch in front of Wallenstein’s position (3). (c) Phase III: Gustavus is killed during the fighting in the ditch (1) in front of the imperial lines, and Wallenstein’s centre holds. The imperial general orders Ottavio Piccolomini to the left (2) and the flank is stabilized (3). (d) Phase IV: Seeking to avenge their fallen king, the Swedes launch an infantry attack on their left that captures the town of Lützen (1) and wrests control of the artillery park on Windmill Hill (2) from the imperialists (3). (e) Phase V: As night descends, Wallenstein orders a retreat (1) as the Swedes consolidate their gains (2). Both sides have lost about one-third of their forces in the action.

With the Swedish king dead and the imperial centre holding, it looked as if Wallenstein had won the day. But a strong attack on the left by Swedish soldiers bent on avenging the death of their king captured the town of Lützen and the nearby artillery park on the rise, forcing Wallenstein to retreat by cover of darkness (Map 7.5(d) and (e)). Both sides lost about one-third of their forces. Wallenstein withdrew his army to Bohemia, leaving Saxony to the Swedes and their Protestant allies. After the death of Gustavus, Swedish influence in the Thirty Years War waned. In 1635 France entered the war against the Habsburgs, ending the emperor’s goal of a centralized and religiously homogeneous empire. Order was restored to Germany in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia, ending a generation of religious warfare.

Although the battle of Lützen was strategically inconclusive, its significance lies in Wallenstein’s adoption of many of Gustavus’s tactical innovations. After the conclusion of the Swedish phase of the Thirty Years War in 1634, European armies increasingly utilized their cavalry in shock action, though missile fire in the form of pistol shot was to remain an important ancillary weapon for European horsemen. But Gustavus’s most important legacy was his revolution of infantry tactics, dispensing with the Swiss-style battle square and making the linear infantry formation the standard for his new model army. He reintroduced a well-articulated line-based combined-arms tactical system to the art of war in early modern Europe, one not seen for well over a millennium.

Gustavus brought to the defence of Protestant Europe a brilliant syncretism of old and new, making efficient use of the best technology of the day, including improved matchlocks, carbines, wheel lock pistols, pre-measured paper cartridges and light artillery. Building on the classical reforms of Maurice of Nassau, Gustavus created a new model national army, complete with uniforms, twenty-year enlistment contracts and an efficient tax-collecting apparatus. He was a tactical visionary, fully recognizing the ‘Age of Gunpowder’ had eclipsed the ‘Age of Polearms’. His light infantry’s adroit use of rolling and volley fire from a linear formation set a precedent that would last as long as muzzle loading, well into the nineteenth century. He changed cavalry doctrine to better support infantry, and he utilized mobile artillery in direct support of the battalion in a way Napoleon would be proud of. Perhaps even more importantly, Gustavus succeeded in converting the thousands of mercenary officers he used in his campaigns in Germany into like-minded soldiers. After his successes at Breitenfeld and Lützen, these same soldiers and their adversaries would return to their own soil and build national armies based on the innovations of the young Swedish king and the Dutch tactical system.