9

Telegram to President Roosevelt — My Visit to Tours — Increasing Degeneration — M. Baudouin — The Great Mandel — Conversation with Reynaud — My Refusal to Release France from the Obligation of March 28, 1940 — Resolute Attitude of MM. Herriot and Jeanneney — “L’Homme du Destin” — French Government Decide to Move to Bordeaux — President Roosevelt to M. Reynaud, June 13 — My Telegram to the President — And to Reynaud — “Indissoluble Union of France and Britain” — Disappointing Telegram from the President — My Telegram to the President of June 14/15 — A Grave Suggestion — Great Battle of June 9 Along the Aisne — Defeat of the French — Forlorn Resistance on the Maginot Line — Our Slender Contribution — General Brooke’s New Command — Talk of a Bridgehead in Brittany — Brooke Declares the Military Situation Hopeless — I Agree — Our Troops Withdraw and Re-embark, June 16/17 — The Pétain Government Asks for an Armistice — A Second Dunkirk Evacuation — A Hundred and Fifty Thousand British and Forty-two Thousand Poles Carried to Britain — The “Lancastria” Horror — My Message of June 16 to the Dominion Prime Ministers — My Hopes of the Air Battle over Britain.

FUTURE GENERATIONS may deem it noteworthy that the supreme question of whether we should fight on alone never found a place upon the War Cabinet agenda. It was taken for granted and as a matter of course by these men of all parties in the State, and we were much too busy to waste time upon such unreal, academic issues. We were united also in viewing the new phase with good confidence. It was decided to tell the Dominions the whole facts. I was invited to send a message in the same sense to President Roosevelt, and also to sustain the determination of the French Government and assure them of our utmost support.

|

Former Naval Person to President Roosevelt. |

12.VI.40. |

I spent last night and this morning at the French G.Q.G., where the situation was explained to me in the gravest terms by Generals Weygand and Georges. You have no doubt received full particulars from Mr. Bullitt. The practical point is what will happen when and if the French front breaks, Paris is taken, and General Weygand reports formally to his Government that France can no longer continue what he calls “co-ordinated war.” The aged Marshal Pétain, who was none too good in April and July, 1918, is, I fear, ready to lend his name and prestige to a treaty of peace for France. Reynaud, on the other hand, is for fighting on, and he has a young General de Gaulle, who believes much can be done. Admiral Darlan declares he will send the French Fleet to Canada. It would be disastrous if the two big modern ships fell into bad hands. It seems to me that there must be many elements in France who will wish to continue the struggle either in France or in the French colonies, or in both. This, therefore, is the moment for you to strengthen Reynaud the utmost you can, and try to tip the balance in favour of the best and longest possible French resistance. I venture to put this point before you, although I know you must understand it as well as I do.

* * * * *

On June 13 I made my last visit to France for four years almost to a day. The French Government had now withdrawn to Tours, and tension had mounted steadily. I took Edward Halifax and General Ismay with me, and Max Beaverbrook volunteered to come too. In trouble he is always buoyant. This time the weather was cloudless, and we sailed over in the midst of our Hurricane squadron, making, however, a rather wider sweep to the southward than before. Arrived over Tours, we found the airport had been heavily bombed the night before, but we and all our escort landed smoothly in spite of the craters. Immediately one sensed the increasing degeneration of affairs. No one came to meet us or seemed to expect us. We borrowed a service car from the Station Commander and motored into the city, making for the préfecture, where it was said the French Government had their headquarters. No one of consequence was there, but Reynaud was reported to be motoring in from the country, and Mandel was also to arrive soon.

It being already nearly two o’clock, I insisted upon luncheon, and after some parleyings we drove through streets crowded with refugees’ cars, most of them with a mattress on top and crammed with luggage. We found a café, which was closed but after explanations we obtained a meal. During luncheon I was visited by M. Baudouin, an official of the French Foreign Office, whose influence had risen in these latter days. He began at once in his soft, silky manner about the hopelessness of the French resistance. If the United States would declare war on Germany, it might be possible for France to continue. What did I think about this? I did not discuss the question further than to say that I hoped America would come in, and that we should certainly fight on. He afterwards, I was told, spread it about that I had agreed that France should surrender unless the United States came in.

We then returned to the préfecture, where Mandel, Minister of the Interior, awaited us. This faithful former secretary of Clemenceau, and a bearer forward of his life’s message, seemed in the best of spirits. He was energy and defiance personified. His luncheon, an attractive chicken, was uneaten on the tray before him. He was a ray of sunshine. He had a telephone in each hand, through which he was constantly giving orders and decisions. His ideas were simple: fight on to the end in France, in order to cover the largest possible movement into Africa. This was the last time I saw this valiant Frenchman. The restored French Republic rightly shot to death the hirelings who murdered him. His memory is honoured by his countrymen and their Allies.

Presently M. Reynaud arrived. At first he seemed depressed. General Weygand had reported to him that the French armies were exhausted. The line was pierced in many places; refugees were pouring along all the roads through the country, and many of the troops were in disorder. The Generalissimo felt it was necessary to ask for an armistice while there were still enough French troops to keep order until peace could be made. Such was the military advice. He would send that day a further message to Mr. Roosevelt saying that the last hour had come and that the fate of the Allied cause lay in America’s hand. Hence arose the alternative of armistice and peace.

M. Reynaud proceeded to say that the Council of Ministers had on the previous day instructed him to inquire what would be Britain’s attitude should the worst come. He himself was well aware of the solemn pledge that no separate peace would be entered into by either ally. General Weygand and others pointed out that France had already sacrificed everything in the common cause. She had nothing left; but she had succeeded in greatly weakening the common foe. It would in those circumstances be a shock if Britain failed to concede that France was physically unable to carry on, if France was still expected to fight on and thus deliver up her people to the certainty of corruption and evil transformation at the hands of ruthless specialists in the art of bringing conquered peoples to heel. That then was the question which he had to put. Would Great Britain realise the hard facts with which France was faced?

The official British record reads as follows:

Mr. Churchill said that Great Britain realised how much France had suffered and was suffering. Her own turn would come, and she was ready. She grieved to find that her contribution to the land struggle was at present so small, owing to the reverses which had been met with as a result of applying an agreed strategy in the North. The British had not yet felt the German lash, but were aware of its force. They nevertheless had but one thought: to win the war and destroy Hitlerism. Everything was subordinate to that aim; no difficulties, no regrets, could stand in the way. He was well assured of British capacity for enduring and persisting, for striking back till the foe was beaten. They would therefore hope that France would carry on fighting south of Paris down to the sea, and if need be from North Africa. At all costs time must be gained. The period of waiting was not limitless: a pledge from the United States would make it quite short. The alternative course meant destruction for France quite as certainly. Hitler would abide by no pledges. If, on the other hand, France remained in the struggle, with her fine Navy, her great Empire, her Army still able to carry on guerrilla warfare on a gigantic scale, and if Germany failed to destroy England, which she must do or go under, if then Germany’s might in the air was broken, then the whole hateful edifice of Nazidom would topple over. Given immediate help from America, perhaps even a declaration of war, victory was not so far off. At all events England would fight on. She had not and would not alter her resolve: no terms, no surrender. The alternatives for her were death or victory. That was his answer to M. Reynaud’s question.

M. Reynaud replied that he had never doubted England’s determination. He was, however, anxious to know how the British Government would react in a certain contingency. The French Government – the present one or another – might say: “We know you will carry on. We would also, if we saw any hope of a victory. But we see no sufficient hopes of an early victory. We cannot count on American help. There is no light at the end of the tunnel. We cannot abandon our people to indefinite German domination. We must come to terms. We have no choice….” It was already too late to organise a redoubt in Brittany. Nowhere would a genuine French Government have a hope of escaping capture on French soil…. The question to Britain would therefore take the form: “Will you acknowledge that France has given her best, her youth and life-blood; that she can do no more; and that she is entitled, having nothing further to contribute to the common cause, to enter into a separate peace while maintaining the solidarity implicit in the solemn agreement entered into three months previously?”

Mr. Churchill said that in no case would Britain waste time and energy in reproaches and recriminations. That did not mean that she would consent to action contrary to the recent agreement. The first step ought to be M. Reynaud’s further message putting the present position squarely to President Roosevelt. Let them await the answer before considering anything else. If England won the war, France would be restored in her dignity and in her greatness.

All the same I thought the issue raised at this point was so serious that I asked to withdraw with my colleagues before answering it. So Lords Halifax and Beaverbrook and the rest of our party went out into a dripping but sunlit garden and talked things over for half an hour. On our return I restated our position. We could not agree to a separate peace however it might come. Our war aim remained the total defeat of Hitler, and we felt that we could still bring this about. We were therefore not in a position to release France from her obligation. Whatever happened, we would level no reproaches against France; but that was a different matter from consenting to release her from her pledge. I urged that the French should now send a new appeal to President Roosevelt, which we would support from London. M. Reynaud agreed to do this, and promised that the French would hold on until the result of his final appeal was known.

Before leaving, I made one particular request to M. Reynaud. Over four hundred German pilots, the bulk of whom had been shot down by the R.A.F., were prisoners in France. Having regard to the situation, they should be handed over to our custody. M. Reynaud willingly gave this promise, but soon he had no power to keep it. These German pilots all became available for the Battle of Britain, and we had to shoot them down a second time.

* * * * *

At the end of our talk, M. Reynaud took us into the adjoining room, where MM. Herriot and Jeanneney, the Presidents of the Chamber and Senate respectively, were seated. Both these French patriots spoke with passionate emotion about fighting on to the death. As we went down the crowded passage into the courtyard, I saw General de Gaulle standing stolid and expressionless at the doorway. Greeting him, I said in a low tone, in French: “L’homme du destin.” He remained impassive. In the courtyard there must have been more than a hundred leading Frenchmen in frightful misery. Clemenceau’s son was brought up to me. I wrung his hand. The Hurricanes were already in the air, and I slept sound on our swift and uneventful journey home. This was wise, for there was a long way to go before bedtime.

* * * * *

After our departure from Tours at about half-past five, M. Reynaud met his Cabinet again at Cangé. They were vexed that I and my colleagues had not come there to join them. We should have been very willing to do so, no matter how late we had to fly home. But we were never invited; nor did we know there was to be a French Cabinet meeting.

At Cangé the decision was taken to move the French Government to Bordeaux, and Reynaud sent off his telegram to Roosevelt with its desperate appeal for the entry on the scene at least of the American Fleet.

At 10.15 P.M. I made my new report to the Cabinet. My account was endorsed by my two companions. While we were still sitting, Ambassador Kennedy arrived with President Roosevelt’s reply to Reynaud’s appeal of June 10.

|

President Roosevelt to M. Reynaud. |

13.VI.40. |

Your message of June 10 has moved me very deeply. As I have already stated to you and to Mr. Churchill, this Government is doing everything in its power to make available to the Allied Governments the material they so urgently require, and our efforts to do still more are being redoubled. This is so because of our faith in and our support of the ideals for which the Allies are fighting.

The magnificent resistance of the French and British Armies has profoundly impressed the American people.

I am, personally, particularly impressed by your declaration that France will continue to fight on behalf of Democracy, even if it means slow withdrawal, even to North Africa and the Atlantic. It is most important to remember that the French and British Fleets continue [in] mastery of the Atlantic and other oceans; also to remember that vital materials from the outside world are necessary to maintain all armies.

I am also greatly heartened by what Prime Minister Churchill said a few days ago about the continued resistance of the British Empire, and that determination would seem to apply equally to the great French Empire all over the world. Naval power in world affairs still carries the lessons of history, as Admiral Darlan well knows.

We all thought the President had gone a very long way. He had authorised Reynaud to publish his message of June 10, with all that that implied, and now he had sent this formidable answer. If, upon this, France decided to endure the further torture of the war, the United States would be deeply committed to enter it. At any rate, it contained two points which were tantamount to belligerence: first, a promise of all material aid, which implied active assistance; secondly, a call to go on fighting even if the Government were driven right out of France. I sent our thanks to the President immediately, and I also sought to commend the President’s message to Reynaud in the most favourable terms. Perhaps these points were stressed unduly; but it was necessary to make the most of everything we had or could get.

|

Former Naval Person to President Roosevelt. |

13.VI.40. |

Ambassador Kennedy will have told you about the British meeting today with the French at Tours, of which I showed him our record. I cannot exaggerate its critical character. They were very nearly gone. Weygand had advocated an armistice while he still has enough troops to prevent France from lapsing into anarchy. Reynaud asked us whether, in view of the sacrifices and sufferings of France, we would release her from the obligation about not making a separate peace. Although the fact that we have unavoidably been out of this terrible battle weighed with us, I did not hesitate in the name of the British Government to refuse consent to an armistice or separate peace. I urged that this issue should not be discussed until a further appeal had been made by Reynaud to you and the United States, which I undertook to second. Agreement was reached on this, and a much better mood prevailed for the moment in Reynaud and his Ministers.

Reynaud felt strongly that it would be beyond his power to encourage his people to fight on without hope of ultimate victory, and that that hope could only be kindled by American intervention up to the extreme limit open to you. As he put it, they wanted to see light at the end of the tunnel.

While we were flying back here your magnificent message was sent, and Ambassador Kennedy brought it to me on my arrival. The British Cabinet were profoundly impressed, and desire me to express their gratitude for it, but, Mr. President, I must tell you that it seems to me absolutely vital that this message should be published tomorrow, June 14, in order that it may play the decisive part in turning the course of world history. It will, I am sure, decide the French to deny Hitler a patched-up peace with France. He needs this peace in order to destroy us and take a long step forward to world mastery. All the far-reaching plans, strategic, economic, political, and moral, which your message expounds, may be still-born if the French cut out now. Therefore, I urge that the message should be published now. We realise fully that the moment Hitler finds he cannot dictate a Nazi peace in Paris, he will turn his fury onto us. We shall do our best to withstand it. and if we succeed wide new doors are open upon the future and all will come out even at the end of the day.

To M. Reynaud I sent this message:

13.VI.40.

On returning here we received a copy of President Roosevelt’s answer to your appeal of June 10. Cabinet is united in considering this magnificent document as decisive in favour of the continued resistance of France in accordance with your own declaration of June 10 about fighting before Paris, behind Paris, in a province, or, if necessary, in Africa or across the Atlantic. The promise of redoubled material aid is coupled with definite advice and exhortation to France to continue the struggle even under the grievous conditions which you mentioned. If France on this message of President Roosevelt’s continues in the field and in the war, we feel that the United States is committed beyond recall to take the only remaining step, namely, becoming a belligerent in form as she already has constituted herself in fact. Constitution of United States makes it impossible, as you foresaw, for the President to declare war himself, but, if you act on his reply now received, we sincerely believe that this must inevitably follow. We are asking the President to allow publication of the message, but, even if he does not agree to this for a day or two, it is on the record and can afford the basis for your action. I do beg you and your colleagues, whose resolution we so much admired today, not to miss this sovereign opportunity of bringing about the world-wide oceanic and economic coalition which must be fatal to Nazi domination. We see before us a definite plan of campaign, and the light which you spoke of shines at the end of the tunnel.

Finally, in accordance with the Cabinet’s wishes, I sent a formal message of good cheer to the French Government in which the note of an indissoluble union between our two countries was struck for the first time.

|

Prime Minister to M. Reynaud. |

13.VI.40. |

In this solemn hour for the British and French nations and for the cause of Freedom and Democracy to which they have avowed themselves, His Majesty’s Government desire to pay to the Government of the French Republic the tribute which is due to the heroic fortitude and constancy of the French armies in battle against enormous odds. Their effort is worthy of the most glorious traditions of France, and has inflicted deep and long-lasting injury upon the enemy’s strength. Great Britain will continue to give the utmost aid in her power. We take this opportunity of proclaiming the indissoluble union of our two peoples and of our two Empires. We cannot measure the various forms of tribulation which will fall upon our peoples in the near future. We are sure that the ordeal by fire will only fuze them together into one unconquerable whole. We renew to the French Republic our pledge and resolve to continue the struggle at all costs in France, in this island, upon the oceans, and in the air, wherever it may lead us, using all our resources to the utmost limit and sharing together the burden of repairing the ravages of war. We shall never turn from the conflict until France stands safe and erect in all her grandeur, until the wronged and enslaved states and peoples have been liberated, and until civilisation is freed from the nightmare of Nazidom. That this day will dawn we are more sure than ever. It may dawn sooner than we now have the right to expect.

All these three messages were drafted by me before I went to bed after midnight on the 13th. They were written actually in the small hours of the 14th.

The next day arrived a telegram from the President explaining that he could not agree to the publication of his message to Reynaud. He himself, according to Mr. Kennedy, had wished to do so, but the State Department, while in full sympathy with him, saw the gravest dangers. The President thanked me for my account of the meeting at Tours and complimented the British and French Governments on the courage of their troops. He renewed the assurances about furnishing all possible material and supplies; but he then said he had told Ambassador Kennedy to inform me that his message of the 14th was in no sense intended to commit and did not commit the Government of the United States to military participation. There was no authority under the American Constitution except Congress which could make any commitment of that nature. He bore particularly in mind the question of the French Fleet. Congress, at his desire, had appropriated fifty million dollars for the purpose of supplying food and clothing to civilian refugees in France. Finally he assured me that he appreciated the significance and weight of what I had set forth in my message.

This was a disappointing telegram.

Around our table we all fully understood the risks the President ran of being charged with exceeding his constitutional authority, and consequently of being defeated on this issue at the approaching election, on which our fate, and much more, depended. I was convinced that he would give up life itself, to say nothing of public office, for the cause of world freedom now in such awful peril. But what would have been the good of that? Across the Atlantic I could feel his suffering. In the White House the torment was of a different character from that of Bordeaux or London. But the degree of personal stress was not unequal.

In my reply I tried to arm the President with some arguments which he could use to others about the danger to the United States if Europe fell and Britain failed. This was no matter of sentiment, but of life and death.

|

Former Naval Person to President Roosevelt. |

14-15.VI.40. |

I am grateful to you for your telegram and I have reported its operative passages to Reynaud, to whom I had imparted a rather more sanguine view. He will, I am sure, be disappointed at non-publication. I understand all your difficulties with American public opinion and Congress, but events are moving downward at a pace where they will pass beyond the control of American public opinion when at last it is ripened. Have you considered what offers Hitler may choose to make to France? He may say, “Surrender the Fleet intact and I will leave you Alsace-Lorraine,” or alternatively, “If you do not give me your ships, I will destroy your towns.” I am personally convinced that America will in the end go to all lengths, but this moment is supremely critical for France. A declaration that the United States will if necessary enter the war might save France. Failing that, in a few days French resistance may have crumpled and we shall be left alone.

Although the present Government and I personally would never fail to send the Fleet across the Atlantic if resistance was beaten down here, a point may be reached in the struggle where the present Ministers no longer have control of affairs and when very easy terms could be obtained for the British island by their becoming a vassal state of the Hitler Empire. A pro-German Government would certainly be called into being to make peace, and might present to a shattered or a starving nation an almost irresistible case for entire submission to the Nazi will. The fate of the British Fleet, as I have already mentioned to you, would be decisive on the future of the United States, because, if it were joined to the fleets of Japan, France, and Italy and the great resources of German industry, overwhelming sea power would be in Hitler’s hands. He might of course use it with a merciful moderation. On the other hand, he might not. This revolution in sea power might happen very quickly, and certainly long before the United States would be able to prepare against it. If we go down you may have a United States of Europe under the Nazi command far more numerous, far stronger, far better armed than the New World.

I know well, Mr. President, that your eye will already have searched these depths, but I feel I have the right to place on record the vital manner in which American interests are at stake in our battle and that of France.

I am sending you through Ambassador Kennedy a paper on destroyer strength prepared by the Naval Staff for your information. If we have to keep, as we shall, the bulk of our destroyers on the East Coast to guard against invasion, how shall we be able to cope with a German-Italian attack on the food and trade by which we live? The sending of the thirty-five destroyers as I have already described will bridge the gap until our new construction comes in at the end of the year. Here is a definite practical and possibly decisive step which can be taken at once, and I urge most earnestly that you will weigh my words.

* * * * *

Meanwhile the situation on the French front went from bad to worse. The German operations northwest of Paris, in which our 51st Division had been lost, had brought the enemy, by June 9, to the lower reaches of the Seine and the Oise. On the southern banks the dispersed remnants of the Tenth and Seventh French Armies were hastily organising a defence; they had been riven asunder, and to close the gap the garrison of the capital, the so-called Armée de Paris, had been marched out and interposed.

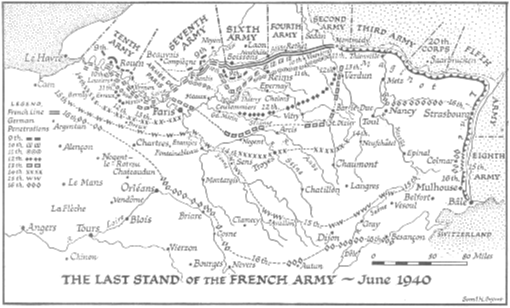

Farther to the east, along the Aisne, the Sixth, Fourth, and Second Armies were in far better shape. They had had three weeks in which to establish themselves and to absorb such reinforcements as had been sent. During all the period of Dunkirk and of the drive to Rouen they had been left comparatively undisturbed, but their strength was small for the hundred miles they had to hold, and the enemy had used the time to concentrate against them a great mass of divisions to deliver the final blow. On June 9 it fell. Despite a dogged resistance, for the French were now fighting with great resolution, bridgeheads were established south of the river from Soissons to Rethel, and in the next two days these were expanded until the Marne was reached. German Panzer divisions which had played so decisive a part in the drive down the coast were brought across to join the new battle. Eight of these, in two great thrusts, turned the French defeat into a rout. The French armies, decimated and in confusion, were quite unable to withstand this powerful assembly of superior numbers, equipment, and technique. In four days, by June 16, the enemy had reached Orléans and the Loire; while to the east the other thrust had passed through Dijon and Besançon, almost to the Swiss frontier.

West of Paris the remains of the Tenth Army, the equivalent of no more than two divisions, had been pressed back south-westward from the Seine towards Alençon. The capital fell on the 14th; its defending armies, the Seventh and the Armée de Paris, were scattered; a great gap now separated the exiguous French and British forces in the west from the rest and the remains of the once proud Army of France.

And what of the Maginot Line, the shield of France, and its defenders? Until June 14 no direct attack was made, and already some of the active formations, leaving behind the garrison troops, had started to join, if they could, the fast-withdrawing armies of the centre. But it was too late. On that day the Maginot Line was penetrated before Saarbruecken and across the Rhine by Colmar; the retreating French were caught up in the battle and unable to extricate themselves. Two days later the German penetration to Besançon had cut off their retreat. More than four hundred thousand men were surrounded without hope of escape. Many encircled garrisons held out desperately; they refused to surrender until after the armistice, when French officers were despatched to give them the order. The last forts obeyed on June 30, the commander protesting that his defences were still intact at every point.

Thus the vast disorganised battle drew to its conclusion all along the French front. It remains only to recount the slender part which the British were able to play.

* * * * *

General Brooke had won distinction in the retreat to Dunkirk, and especially by his battle in the gap opened by the Belgian surrender. We had therefore chosen him to command the British troops which remained in France and all reinforcements until they should reach sufficient numbers to require the presence of Lord Gort as an Army Commander. Brooke had now arrived in France, and on the 14th he met Generals Weygand and Georges. Weygand stated that the French forces were no longer capable of organised resistance or concerted action. The French Army was broken into four groups, of which its Tenth Army was the westernmost. Weygand also told him that the Allied Governments had agreed that a bridgehead should be created in the Brittany peninsula, to be held jointly by the French and British troops on a line running roughly north and south through Rennes. He ordered him to deploy his forces on a defensive line running through this town. Brooke pointed out that this line of defence was a hundred and fifty kilometres long and required at least fifteen divisions. He was told that the instructions he was receiving must be regarded as an order.

It is true that on June 11 at Briare, Reynaud and I had agreed to try to draw a kind of “Torres Vedras line” across the foot of the Brittany peninsula. Everything, however, was dissolving at the same time, and the plan, for what it was worth, never reached the domain of action. In itself the idea was sound, but there were no facts to clothe it with reality. Once the main French armies were broken or destroyed, this bridgehead, precious though it was, could not have been held for long against concentrated German attack. But even a few weeks’ resistance here would have maintained contact with Britain and enabled large French withdrawals to Africa from other parts of the immense front, now torn to shreds. If the battle in France was to continue, it could be only in the Brest peninsula and in wooded or mountainous regions like the Vosges. The alternative for the French was surrender. Let none, therefore, mock at the conception of a bridgehead in Brittany. The Allied armies under Eisenhower, then an unknown American colonel, bought it back for us later at a high price.

General Brooke, after his talk with the French commanders, and having measured from his own headquarters a scene which was getting worse every hour, reported to the War Office and by telephone to Mr. Eden that the position was hopeless. All further reinforcements should be stopped, and the remainder of the British Expeditionary Force, now amounting to a hundred and fifty thousand men, should be re-embarked at once. On the night of June 14, as I was thought to be obdurate, he rang me up on a telephone line which by luck and effort was open, and pressed this view upon me. I could hear quite well, and after ten minutes I was convinced that he was right and we must go. Orders were given accordingly. He was released from French command. The back-loading of great quantities of stores, equipment, and men began. The leading elements of the Canadian Division which had landed got back into their ships, and the 52d Division, which, apart from its 157th Brigade, had not yet been committed to action, retreated on Brest. No British troops operating under the Tenth French Army were withdrawn; but all else of ours took to the ships at Brest, Cherbourg, St. Malo, and St. Nazaire. On June 15 our troops were released from the orders of the Tenth French Army, and next day, when it carried out a further withdrawal to the south, they moved towards Cherbourg. The 157th Brigade, after heavy fighting, was extricated that night, and, retiring in their lorries, embarked during the night of June 17/18. On June 17 it was announced that the Pétain Government had asked for an armistice, ordering all French forces to cease fighting, without even communicating this information to our troops. General Brooke was consequently told to come away with all men he could embark and any equipment he could save.

We repeated now on a considerable scale, though with larger vessels, the Dunkirk evacuation. Over twenty thousand Polish troops who refused to capitulate cut their way to the sea and were carried by our ships to Britain. The Germans pursued our forces at all points. In the Cherbourg peninsula they were in contact with our rearguard ten miles south of the harbour on the morning of the 18th. The last ship left at 4 P.M., when the enemy were within three miles of the port. Very few prisoners were caught.

In all there were evacuated from all French harbours 136,000 British troops and 310 guns; a total, with the Poles, of 156,000 men. This reflects great credit on General Brooke’s embarkation staff, of whom the chief, General de Fonblanque, a British officer, died shortly afterwards as the result of his exertions.

At Brest and the Western ports the evacuations were numerous. The German air attack on the transports was heavy. One frightful incident occurred on the 17th at St. Nazaire. The 20,000-ton liner Lancastria, with five thousand men on board, was bombed and set on fire just as she was about to leave. A mass of flaming oil spread over the water round the ship, and upwards of three thousand men perished. The rest were rescued under continued air attack by the devotion of the small craft. When this news came to me in the quiet Cabinet Room during the afternoon, I forbade its publication, saying, “The newspapers have got quite enough disaster for today at least.” I had intended to release the news a few days later, but events crowded upon us so black and so quickly that I forgot to lift the ban, and it was some years before the knowledge of this horror became public.

* * * * *

To lessen the shock of the impending French surrender, it was necessary at this time to send a message to the Dominion Prime Ministers showing them that our resolve to continue the struggle although alone was not based upon mere obstinacy or desperation, and to convince them by practical and technical reasons, of which they might well be unaware, of the real strength of our position. I therefore dictated the following statement on the afternoon of June 16, a day already filled with much business.

|

Prime Minister to the Prime Ministers of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. |

16.VI.40. |

[After some sentences of introduction particular to each:]

I do not regard the situation as having passed beyond our strength. It is by no means certain that the French will not fight on in Africa and at sea, but, whatever they do, Hitler will have to break us in this island or lose the war. Our principal danger is his concentrated air attack by bombing, coupled with parachute and air-borne landings and attempts to run an invading force across the sea. This danger has faced us ever since the beginning of the war, and the French could never have saved us from it, as he could always switch onto us. Undoubtedly, it is aggravated by the conquests Hitler has made upon the European coast close to our shores. Nevertheless, in principle the danger is the same. I do not see why we should not be able to meet it. The Navy has never pretended to prevent a raid of five or ten thousand men, but we do not see how a force of, say, eighty to a hundred thousand could be transported across the sea, and still less maintained, in the teeth of superior sea power. As long as our Air Force is in being it provides a powerful aid to the Fleet in preventing sea-borne landings and will take a very heavy toll of air-borne landings.

Although we have suffered heavy losses by assisting the French and during the Dunkirk evacuation, we have managed to husband our air-fighter strength in spite of poignant appeals from France to throw it improvidently into the great land battle, which it could not have turned decisively. I am happy to tell you that it is now as strong as it has ever been, and that the flow of machines is coming forward far more rapidly than ever before; in fact, pilots have now become the limiting factor at the moment. Our fighter aircraft have been wont to inflict a loss of two or two and a half to one even when fighting under the adverse conditions in France. During the evacuation of Dunkirk, which was a sort of No Man’s Land, we inflicted a loss of three or four to one, and often saw German formations turn away from a quarter of their numbers of our planes. But all air authorities agree that the advantage in defending this country against an oversea air attack will be still greater because, first, we shall know pretty well by our various devices where they are coming, and because our squadrons lie close enough together to enable us to concentrate against the attackers and provide enough to attack both the bombers and the protecting fighters at the same time. All their shot-down machines will be total losses; many of ours and our pilots will fight again. Therefore, I do not think it by any means impossible that we may so maul them that they will find daylight attacks too expensive.

The major danger will be from night attack on our aircraft factories, but this, again, is far less accurate than daylight attack, and we have many plans for minimising its effect. Of course, their numbers are much greater than ours, but not so much greater as to deprive us of a good and reasonable prospect of wearing them out after some weeks or even months of air struggle. Meanwhile, of course, our bomber force will be striking continually at their key points, especially oil refineries and air factories and at their congested and centralised war industry in the Ruhr. We hope our people will stand up to this bombardment as well as the enemy. It will, on both sides, be on an unprecedented scale. All our information goes to show that the Germans have not liked what they have got so far.

It must be remembered that, now that the B.E.F. is home and largely rearmed or rearming, if not upon a Continental scale, at any rate good enough for Home defence, we have far stronger military forces in this island than we have ever had in the late war or in this war. Therefore, we hope that such numbers of the enemy as may be landed from the air or by sea-borne raid will be destroyed and be an example to those who try to follow. No doubt we must expect novel forms of attack and attempts to bring tanks across the sea. We are preparing ourselves to deal with these as far as we can foresee them. No one can predict or guarantee the course of a life-and-death struggle of this character, but we shall certainly enter upon it in good heart.

I have given you this full explanation to show you that there are solid reasons behind our resolve not to allow the fate of France, whatever it may be, to deter us from going on to the end. I personally believe that the spectacle of the fierce struggle and carnage in our island will draw the United States into the war, and even if we should be beaten down through the superior numbers of the enemy’s Air Force, it will always be possible, as I indicated to the House of Commons in my last speech, to send our fleets across the oceans, where they will protect the Empire and enable it to continue the war and the blockade, I trust in conjunction with the United States, until the Hitler régime breaks under the strain. We shall let you know at every stage how you can help, being assured that you will do all in human power, as we, for our part, are entirely resolved to do.

I composed this in the Cabinet Room, and it was typed as I spoke. The door to the garden was wide open, and outside the sun shone warm and bright. Air Chief Marshal Newall, the Chief of the Air Staff, sat on the terrace meanwhile, and when I had finished revising the draft, I took it out to him in case there were any improvements or corrections to be made. He was evidently moved, and presently said he agreed with every word. I was comforted and fortified myself by putting my convictions upon record, and when I read the message over the final time before sending it off, I felt a glow of sober confidence. This was certainly justified by what happened. All came true.