On 2 September 1945, Ho Chi Minh, leader of the Indochina Communist Party, and effective leader of the revolt against the Japanese invaders, declared Vietnamese independence in Saigon. Although this ceremony was witnessed by several US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) agents sent to coordinate opposition to the Japanese, the French were quick to reclaim their former grip on their colonies in Indochina. Within a month of Ho’s proclamation, they had initiated a military campaign against the Viet Minh, with the primary intention of re-establishing their influence in the country.

From the start of 1946 until the outbreak of the First Indochina War in December 1946, both sides demonstrated a willingness to negotiate, while pursuing low-level military action against the other. By 6 March 1946, a preliminary agreement had been reached recognizing the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) as a Free State within the French Union, with referendums over the future of the provinces of Cochinchina, Annam and Tonkin to follow. Unfortunately, neither French officials in Vietnam, nor Ho’s supporters were satisfied with the agreement, and both groups seemed content to see the situation drift towards civil war.

The trigger for war came in late November 1946 when the French commander in Indochina, General Jean-Etienne Valluy, authorized the bombardment of the Vietnamese settlement in Haiphong, resulting in approximately 6,000 Vietnamese fatalities. On 19 December, French forces in Hanoi demanded that the occupants of the city surrender their weapons. Authorized to do so by the party leadership, General Giap, Minister of the Interior in the DRV, refused and declared the start of a war of resistance against the French colonialists.

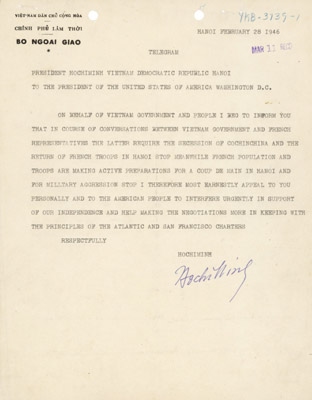

Letter from Ho Chi Minh to President Harry S. Truman, 28 February 1946

NARA

In response to the overwhelming advantage held by the French in terms of weaponry and manpower, the Viet Minh fled to the countryside. Their determination and willingness to absorb huge casualties shocked the French forces, who expected an easy victory. Ho’s adoption of a guerrilla ‘hit and run’ strategy proved effective in the early stages of the war in denying the countryside to the French, which in turn provided a greater opportunity for Ho to wage a political war targeted at the Vietnamese peasantry.

For the US this situation presented a dilemma. The classic Wilsonian liberalism which had underpinned the US approach to both World Wars was resolutely anti-colonialist; indeed the copy of the Declaration of Independence quoted extensively in Ho’s declaration of the Republic of Vietnam in September 1945 was actually provided by US agents. Ho appealed to this strand of liberalism in the months after the end of the war, sending a series of messages to Washington asking for help. None of these were replied to.

The wider context of the Cold War in Europe and Asia, along with suspicions over Ho’s ideological leanings, persuaded both President Truman and Eisenhower that they should not accede to his requests for support. The US did not want to antagonize the French, especially after the creation of NATO in 1949 and the ongoing concern over Germany’s future. Furthermore, the fear of the spread of Communism into Asia from China (communist since 1949) and the start of the Korean War in June 1950, forced the hand of the US. Many in Washington were highly sceptical about Ho’s claims to be a mere nationalist. Indeed, the prevailing view was that nationalism proved to be a convenient fig leaf for all communists to hide behind, in their battles against Western colonial rulers: once the Imperialists had been removed, so the true colours of the guerrillas would appear. In a telegram (20 May 1949) to the US Consulate in Hanoi, US Secretary of State, Dean Acheson summed up this position perfectly in 1949, stating ‘all Stalinists in colonial areas are nationalists.’

In an attempt to counter the Viet Minh’s appeal to Vietnamese nationalists, and to solidify US support, the French introduced a new government in March 1949. It was headed by former Emperor Bao Dai, and had the power to manage its own foreign affairs and establish a Vietnamese army. While the Emperor proved to be an unconvincing advertisement for ‘third force’ politics in Indochina, the outbreak of the Korean War had a significant impact on US attitudes to the communist threat in Asia. As a result of the North Korean invasion over the 38th parallel, US aid increased considerably, to the point it was funding 80 per cent of the French war effort against the Viet Minh. In addition, US involvement in Vietnam started with the creation of the Military Assistance and Advisory Group, Vietnam in September 1950.

Militarily, however, the French lack of manpower in Vietnam restricted their ability to launch the concerted offensives required to capture and hold territory throughout the country. By the middle of 1953, the Viet Minh were approximately 60 per cent strength of the French, but were able to launch more frequent attacks against a foe increasingly committed to defence, and looking for a way to end the conflict. This was the context in which General Henri Navarre developed a plan to lure the Viet Minh into a conventional battle, where he would achieve the decisive victory of the war. He established a strongpoint at Dien bien phu, a remote outpost in the north of the country, chosen so as to prevent Viet Minh infiltration into neighbouring Laos. Its airfield also meant that the garrison could be easily re-supplied by air. Unbeknown to Navarre, Giap had managed to surround the 13,000 troops at the French base with 50,000 men, and co-ordinated the immense physical task of hauling heavy artillery up the mountains surrounding the French position.

The Battle of Dien bien phu started on 13 March 1954. In spite of French diplomatic pressure, the US refused to intervene with airstrikes against the Viet Minh positions, but they did provide ammunitions and material support to the French, in accordance the Mutual Defence Assistance Act. When the battle ended on 7 May, the French casualties were enormous: they suffered almost 3,000 killed, with 10,000 taken prisoner. The DRV gained fresh impetus in the ongoing Geneva peace talks, while the French had to accept that their role in Vietnam’s future was about to come to a swift and ignominious end.