CHAPTER 9

Two weeks before Buchanan’s presidency began, the president-elect secretly intervened in U.S. Supreme Court deliberations. The nonjudge urged the judges to eliminate the issue that could destroy his administration (and his nation). His plea arguably shaped the Court’s so-called Dred Scott Decision, announced two days after his presidential inauguration. Thus did the Border North moderate, in collaboration with the Court’s primarily moderate southern majority, begin a pro-Union administration that would further disunion.

– 1 –

The conventional wisdom about Dred Scott’s southern judges eliminates that irony. Their famous—infamous—Supreme Court decision supposedly threw down the proslavery verdict of southern diehards, determined to save slavery at whatever cost to Union.1But in reality, these judges sought to save the Union from sectional storms, partly in hopes that pacified slaveholders might incrementally reform and perhaps end absolute power. The majority of the judges would stay in the Union during the Civil War, at whatever cost to slavery.

James Buchanan initiated misconceptions of their decision. In his Inaugural Address, the new president declared that the Court’s decision, whatever it turned out to be, would settle the slavery issue forever. Just before Buchanan professed ignorance about what the Court would decide, observers saw him whispering with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney on the inauguration stand.

Forty-eight hours later, Maryland’s Taney read the Supreme Court’s decision. The five Southern Democratic judges (with one Northern Democratic judge concurring and another not dissenting) ruled that Congress could not constitutionally bar slavery from U.S. territories. The verdict implicitly forbade Buchanan’s Republican foes from restoring the Missouri Compromise prohibition of slavery in Kansas and Nebraska territories (and from enacting any other prohibition of territorial slavery). And Buchanan claimed to have had nothing to do with this demolition of his political enemies!

Republicans responded that the Northern Democrats’ dissimulating president (elected without a popular majority) had conspiratorially encouraged proslavery, disunionist Democratic judges (elected by no one) to veto the majority section’s majority: those 1.3 million citizens who had lately voted for John C. Frémont. The conspiratorial part of Republicans’ tale of a disunionist travesty, although sounding like the most preposterous part, was actually the most correct aspect. President-elect Buchanan, while drafting his Inaugural Address, did clandestinely prod jurists toward their decision. Buchanan did secretly learn (slightly incorrectly) about the imminent verdict. He did pretend total unawareness in his Inaugural Address.

But most of the Court’s controlling five southern judges no more cherished slavery or savored disunion than did Buchanan. Instead, their so-called Dred Scott Decision meant to save the Union by declaring the future of slavery none of Yankees’ or the federal government’s business. The judges also hoped that Southerners, once spared northern meddlers’ convulsions, would calmly trim or end absolute power.

If the Supreme Court’s controlling majority had been proslavery ultras and/or disunionists, they would have betrayed the presidents who had nominated them. Southern Democrats commanded the Court in 1857 because the Democratic Party, with its southern power base, had won five of the previous seven presidential elections. The Democracy’s presidents had aspired to stop extremists, North and South, from smashing their party and their Union. Andrew Jackson, father of this Democratic Party statecraft, had appointed three of the five Southern Democrats who ruled the Court in 1857. He had chosen southern moderates who shared his antiabolitionist, antidisunionist position.

Dred Scott’s judges, with one exception, demonstrated that President Jackson and his Jacksonian successors had nominated the right antiextremists. The exception, Virginia’s Peter Daniel, often threatened disunion. When would the North, asked Daniel in 1851, “ever produce anything that is good and decent?”2 If Judge Daniel had lived to see Abraham Lincoln elected president (the jurist died six months earlier), he probably would have been that Virginia rarity: instantly for secession.

In 1860–61, all Peter Daniel’s southern compatriots on the 1857 Supreme Court would disown knee-jerk disunionism. Although Alabama’s John A. Campbell would eventually go along with his Confederate state, he opposed secession so heatedly, sought reunion so ardently, and resigned from the Supreme Court so tardily that his hometown, Mobile, ousted him. Unlike Campbell, Georgia’s James Wayne, Tennessee’s John Catron, and Maryland’s Taney (all Jackson’s own appointees) would never secede, from the nation or from the Civil War bench. Wayne and Catron would pay for their perpetual unionism. Their Confederate states would confiscate personal property worth tens of thousands of dollars from both alleged traitors. The town of Nashville would expel Catron, without his ailing wife. Mr. Justice Catron would answer in Andrew Jackson’s (and James Buchanan’s) spirit: “I have to punish treason, and I will.”3

According to these eternally pro-Union judges, Yankee holier-than-thous undermined not only Americans’ right to own (slave) property but also the requirement of republican Union: that white men must treat each other as equals. Peter Daniel’s unionist colleagues agreed with their fire-eating compatriot that the South’s condescending critics assume “an insulting exclusiveness or superiority” and denounce us for “a degraded inequality or inferiority.” These do-gooders say “in effect to the Southern man, Avaunt! You are not my equal and hence are to be excluded” from America’s territories.4 “We must not suffer ourselves to be depreciated or degraded,” added John Campbell. Looking “our calumniators proudly in the face,” we must “maintain … our equal rank.”5

Dred Scott’s southern judges saw northern calumniators as traitors to black men’s no less than white men’s interests. Outside meddlers did not know the slaveholding world they would tear apart. They did not understand that a delicate institution must be changed slowly. They did not fathom, wrote Roger B. Taney, that “a general and sudden emancipation would be absolute ruin to the negroes.”6 Yankee fanatics did not comprehend, Alabama’s Campbell added, that “we cannot afford to be the subjects of experiment.” As blacks’ guardians, Southerners “must not yield the destinies of this people to… visionaries and unreasonable fanatics; and least of all, to [Yankee] politicians not responsible” to us.7

But these judicial guardians, while slapping outsiders’ hands off insiders’ governance, wondered about unlimited governance over slaves. Peter Daniel, the closest to a defender of black slavery, hired white house servants. James Wayne, whose lowcountry Georgia family had owned huge plantations, retained only nine slaves. He allowed this remnant to hire themselves out, beyond his willpower. So too, John Catron violated his state’s law by permitting some of his Tennessee slaves to live like free blacks. John Campbell and Roger B. Taney gradually manumitted almost all their slaves. None of his liberated slaves, wrote the Border South’s Chief Justice Taney at the time of his so-called Dred Scott Decision, “have disappointed my expectations. … They were worthy of freedom; and knew how to use it.”8

Alabama’s John Campbell and Georgia’s James Wayne took heresy beyond the Border South’s Taney and the Middle South’s Catron. The Lower South’s two judges wanted public reform to complement private manumissions. In an 1847 Southern Quarterly Review article, John Campbell promoted “an important alteration of our law.…The connection of husband and wife, and of parent and child are sacred in a Christian community, and should be rendered secure in the laws of a Christian state.” Creditors, by “frequently” dividing slave families after bankruptcies, had “greatly deteriorated” blacks’ “character and deprived the [master-slave] relation of some of its patriarchal nature.”

Campbell urged patriarchs to provide “more abundant supplies of moral and religious instruction” for slaves and “an increase of their mental cultivation.” He wished southern legislators to limit masters’ use of slave property “as a basis of credit,” when pursuing loans, and to forbid the severing of a slave family, “at the pursuit of a creditor.” Our laws and practices, declared Justice Campbell, “formed when the blacks were fresh from their native Africa, with gross appetites and brutal habits,” have become “the worn out maxims of other ages.” We must instead embrace “progress and amelioration,” with laws that “steadily and systematically … prove that the negro race is susceptible of great improvement.”9

That plea for state curbs on absolute power made sense from Campbell, an ex-slaveholder who had renounced all power over his slaves. But how could the same man slap down federal curbs on slaveholders’ property rights and thus keep the Dred Scotts enslaved? Because none of the Court’s southern judges doubted that a state could abolish or regulate the institution. All of them deplored federal jurisdiction over slavery (and deplored the disunion that overreaching Yankees would provoke). That federal/state distinction underlies the second stunning public document written by Dred Scott’s allegedly proslavery judges: Georgia’s James Wayne’s 1854 address to the American Colonization Society’s annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

Heretically (for a Deep South slaveholder), Wayne urged that the federal government, to promote the general welfare, constitutionally could and ethically should send free blacks back to Africa. Southern ultras had long denounced that argument. If the general welfare required blacks to be removed, couldn’t the general government free more blacks to remove? Wayne answered that Congress could not seize property but could remove property that owners had renounced. No one called removing free Indians to reservations unconstitutional, Wayne pointed out. Why was removing freed slaves to Africa constitutionally different?!

But would not colonization unconstitutionally promote abolition by encouraging more slaveowners to free more blacks? Here Wayne, in the southern manner, covered heretical opinion with verbal fudge. After achieving federal colonization of free blacks, he would “leave the future to that Providence which guides us in mercy.” He mercifully guessed that “the Southwestern States,” although now containing few free blacks, “may soon free” larger numbers, “if governments financed removal” of freedmen. That would be the right reform—“reformation with a slow foot.”

But about slavery’s immorality, the edgy heretic removed the fudge. The Georgia jurist decried proslavery Southerners’ “mistaken” religious views as but “pretext for reducing men into slavery.” The mistake aside, “communal safety may not permit the dissolution of the evil all at once. Rights grow up under such a system, which cannot with justice be suddenly taken away.” Any “untimely interference,” especially when “attempted by an external intervention, out of the sovereignty where it exists,” can only produce “blood-shed, massacre, and war.” But if judges used “our National Constitution” to keep outsiders’ hands off the South, Wayne agreed with Campbell, no longer defensive insiders might slowly meet their philanthropic obligations (emphasis mine).10

In 1857, Judge Wayne’s four southern colleagues perhaps disagreed with his procolonization philanthropy, although Chief Justice Taney had previously called black removal the right road toward black emancipation. So too, Campbell’s compatriots perhaps disagreed with his plea that state governments must curtail masters’ absolute power, although these jurists had curtailed their own unlimited dominion. Still, all these Southern Democrats shared the Wayne-Campbell premises. All fretted about perpetual absolute power. All despised outside critics. All believed that presumptuous interference would drive rightfully angry southern egalitarians out of the Union and beyond reconsideration of slavery’s permanence. By prohibiting federal tampering with slaveholder property rights, they aspired to build a cocoon of safety, sanity, and serenity, for the Union, for slaveholders’ self-respect, and perhaps for the South’s own incremental trimming of unlimited power.

– 2 –

Because the majority of these southern jurists hoped to perpetuate the Union, not to perpetuate unreformed slavery, the Court’s private deliberations in the so-called Dred Scott Case featured a suspenseful debate about whether to uphold Scott’s master in a monumental or unmonumental manner. The Dred Scott Case must be termed so-called because it involved not just Dred Scott’s plea for liberty but also his wife’s parallel suit and the enslaved couple’s mutual plea for their two daughters’ freedom. In that famous fabricated title, the Dred Scott Case, Americans turned a slave family into an invisible institution.11

Mr. and Mrs. Scott’s very visible two cases turned on whether slaves’ temporary residence on free terrain ended their bondage, even if they subsequently resided on enslaved terrain. Dred Scott, a Missouri slave, had lived with his master in Illinois, a free state, and in the Wisconsin and Minnesota territories, congressionally liberated Louisiana Purchase areas. In Wisconsin Territory, Scott had met and married his enslaved wife, Harriet.

After the Scotts’ master returned his slaves to enslaved Missouri, the black husband and wife separately sued for the family’s freedom. After the Missouri Supreme Court decided against the Scott family, the Scotts appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In mid-February 1857, after twice hearing public arguments, the nine judges privately conferred on their key question: not whether to keep the Scotts enslaved but whether to rule against the slaves on sweeping or limited grounds.

To keep the Scotts enslaved on the most sweeping grounds, the Court could decree that neither Congress nor a state could constitutionally abolish slave property. To issue a less sweeping but still monumental judgment, the Court could prohibit only congressional authority to emancipate in the territories.

To decide for the master on nonmonumental grounds, the jurists could throw out the Scotts’ suits, without a word about congressional or state power to emancipate. They could simply uphold the Missouri Supreme Court’s verdict, sanctioning the state legislature’s decree that once serviles returned to Missouri, temporary residence elsewhere did not free them. The Court could also evade a decision on territorial questions by ruling that no black, including the Scotts, could sue in U.S. courts.

The debate in Supreme Court chambers swiftly eliminated two options and made a third problematic. Only the two northern non-Democrats (one already a Republican and the other soon to become one) wished to free the Scotts. None of the seven Democrats wished to deny that a statecould emancipate slaves. Since only three jurists definitely denied that blacks could sue in federal courts, a potential majority on this matter remains problematical.12

A majority could be surely mustered for only two positions. The Court could advance to an historic judgment: that Congress could not emancipate slaves in national territories. Or the judges could retreat to the less historic position: that Missouri’s laws legitimately denied the Scotts’ claim to freedom once they had returned from freed territory. All five Southern Democrats preferred the epic decision against congressional emancipation in federal territories. Both Northern Democrats sought the nonepic evasion of that explosive question.

Those numbers could have precluded debate. Had the Court’s majority, those five Southern Democrats, wished only to perpetuate slavery’s alleged blessings by barring congressional territorial emancipation, they could have issued the ban without listening to the Yankees. But since these Southerners wished to tranquilize the Union by settling the slavery issue, they trembled to issue a solely southern judgment. They feared that if five southern jurists barred congressional territorial emancipation and four northern jurists vehemently dissented, the Union would be further convulsed, not forever calmed.

That fear forced the five Southerners to keep talking to those four Yankees. Perhaps at least the two Northern Democrats would see an historic destiny to save the Union. Then, the five Southerners reasoned, an asectional majority of seven, not a sectional majority of five, could forbid Congress from abolishing slavery in the territories. That apparently more asectional verdict, these southern unionists dreamed, would win national acceptance.

The two Northern Democrats, Samuel Nelson of New York and Robert Grier of Pennsylvania, remained blind to the vision. The two Yankees considered a decision against congressional authority to abolish territorial slavery wildly provocative. They favored a discrete decision: Missouri law must prevail over Missouri slaves.

Sometime during the first week of the debate in chambers, and perhaps on the first day, February 14, 1857, the Southerners surrendered. The seven Democrats appointed New York’s Nelson to write a decision that perpetuated the Scotts’ enslavement solely by upholding Missouri law. Thus blacks’ right to sue in federal courts, the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise, and the constitutionality of state or of congressional emancipations—all those explosive issues would be evaded.

But the five Southerners squirmed at their evasion. Although the Court had ostensibly decided, judges kept on furiously talking in chambers, while Samuel Nelson kept on remorselessly writing an evasively narrow decision. As the Southerners became more strident, the Northerners became more irritated. In the increasingly incriminating atmosphere, Southerners thought they heard (maybe did hear) the two northern non-Democrats threaten to write dissenting opinions, upholding congressional abolition in the national territories. If those Yankees laid down antisouthern pronouncements, Southerners, being Southerners, had to issue answers. So the five Southern Democrats edged toward repudiating their surrender, defying the two Northern Democrats, and issuing an exclusively southern verdict against congressional power to emancipate. But they fretted again that a purely southern decision, with no northern jurist concurring, would provoke a northern scream about a Slave Power conspiracy—a reaction fatal to the Union.

– 3 –

At this grim moment, when all options looked dark, Tennessee’s John Catron endeavored to bring an unprecedented light into the chambers. Although the two Northern Democrats found southern jurists unconvincing, maybe they would heed their fellow Northern Democrat, the presidentelect. If James Buchanan would urge his fellow Pennsylvanian Democrat, Robert Grier, to concur with the southern majority, maybe that stubborn Northern Democrat—and then maybe New York’s even more stubborn Samuel Nelson—would cave in.

On February 3, 1857, Buchanan had written the Tennessee unionist, discreetly asking about only the timing of the Court’s decision. Would the verdict be handed down before his Inaugural Address on March 4? Catron, the most street-smart of the judges and a Buchanan intimate, read between the lines. He discerned that his former roommate’s discreet inquiry about timing clothed an indiscreet inquiry about substance. The president-elect wanted to know not only when but if the Court would save the new administration and the Union from the issue of slavery in the territories. Would the judges thankfully declare the explosive subject out of bounds, for everyone who exerted federal power? Then the shattering question need never bother President Buchanan.

Catron sent less welcome news. On February 6 and more informatively on February 10, the jurist wrote Buchanan that the Scott cases would be decided February 14, when the judges met in conference. (Actually, February 14 turned out to be not the day of decision but the beginning of over a week of deliberation.) Probably, Catron added, you will not “be helped by the decision in preparing your Inaugural.” On “the question of power” over slavery in the territories, the verdict “will settle nothing, in my present opinion” (emphasis his).13

On February 19, Catron sent more promising but still not definitive news, along with a plea for the president-elect’s aid in the still incomplete deliberations. “I think you may safely say” in your Inaugural, Catron now calculated, that the “high and independent” Supreme Court will “settle & decide a controversy which has so long and uselessly agitated the country.” Catron predicted that the two northern non-Democratic judges would force the “majority of my brethren… to this point” (emphasis mine).

Buchanan, as calculating a political operator as his good friend Catron, knew what the judge’s “think” meant. The Court’s deliberations, while heading the right way, had not yet quite arrived at the promised land. That happy but still unfinalized trend gave importance to Catron’s unprecedented appeal. “Will you drop [Robert] Grier a line, saying how necessary it is & how good the opportunity is, to settle the question by an affirmative decision of the Supreme Court, the one way or the other?”

Grier would rule the right way on the question of congressional power in the territories, Catron assured Buchanan, if the president-elect’s fellow Pennsylvania Democrat could be convinced to rule on the issue at all. Grier “has been persuaded” to avoid the subject sheerly “for the sake of repose.” The president-elect need not indiscreetly beg a Supreme Court justice to decide a particular way. Buchanan need only discreetly suggest that the Court would best serve the Union’s “repose” by deciding the matter “one way or the other.”

Buchanan, having received Catron’s appeal on Friday morning, had his plea in Grier’s mailbox the next Monday morning. The haste indicated the president-elect’s urgency about the Court’s looming decision. Buchanan knew that the issue of slavery in the territories could shatter his fragile administration, party, and nation. How sublime if slavery agitation could be thrown forever out of Congress, not by a transient gag rule this time but by a permanent Supreme Court decree. The Court, Buchanan believed, could best achieve the Union’s “repose” not Grier’s way, by ducking Supreme Court controversy, but the southern jurists’ way, by removing the controversy forever from national deliberations.

Grier answered within hours. With the president-elect calling, a patriot (himself no independent thinker) felt compelled to fall in line. While a controversial decision might not serve the Union’s “repose,” the mistake, if so it turned out to be, was now Buchanan’s. With his election, the president-elect arguably had won the right to make such purely political calls.

Before your letter arrived, Grier wrote Buchanan, Samuel “Nelson & myselff” had refused “to commit ourselves” on “the power of Congress & the validity of the [Missouri] compromise act.” Even now, “perhaps Nelson will remain neutral.” But Grier had shown Buchanan’s letter to Wayne and Taney, and the three of them all now “concur in your view” that “an expression of the opinion of the Court on this troublesome question” would be desirable.

Furthermore, Grier regretted, the Court’s two non-Democratic jurists seemed determined to issue their opinion, reaffirming congressional power to emancipate territorial slaves. So the Southern Democrats “feel compelled to express their opinions” against that power. If the Southerners compelled Nelson and himself to decide on the Missouri Compromise, Grier added, the “line of division in the court” must not be between sections. So to secure a nonsectional decision, Grier, Taney, and Wayne, after their conversation about Buchanan’s letter, had agreed to go for denying Congress power to cleanse U.S. territories of slavery and to “use our endeavors to get brothers Daniel & Campbell & Catron to do the same.”

By the same mail, Buchanan received another letter from Catron, written before Grier’s conversion, urging again that Grier must be “speeded.” Then, Catron predicted, “whatever you wish may be accomplished.” Buchanan, having just read Grier’s promise to speed ahead, apparently assumed that all his wishes would now be swiftly accomplished.14

The Court speedily accomplished somewhat less than Buchanan wished. Either the day or the day after Grier received Buchanan’s letter, the converted Pennsylvania Democrat and the five Southern Democrats met, without Nelson, the unconverted New York Democrat, being told of the meeting.15 The rump caucus voted, on Wayne’s motion, that Taney, not Nelson, should speak for the majority. Taney should stress that the Constitution forbade Congress from abolishing slavery in U.S. territories.

Buchanan had hoped for a further decision: that since Congress could not emancipate, the body created by Congress, a territorial legislature, also could not emancipate. That addendum, Buchanan prayed, would sweep slavery controversies out of the territories as well as out of Congress. What bliss, for a vulnerable president-elect who dreaded further slavery controversies over bloody Kansas Territory.

Chief Justice Taney shared that view of bliss. He eventually placed a few sentences, denying territorial legislatures’ right to emancipate, in his final opinion. But the rest of the Court had stopped, at least in chambers, where the Grier-Taney-Wayne conference had planned—with a six-judge majority against congressional emancipation in the territories. Meanwhile, the bypassed Nelson remained silent on this issue, while concurring with the verdict against the Scotts on his own grounds: Missouri law.

Eight days after privately receiving glad tidings from Grier and Catron, the new president publicly declared, in his Inaugural Address, that the question of congressional power over slavery in the territories “legitimately belongs to the Supreme Court of the United States.” The Court, Buchanan mistakenly asserted, would also “speedily and finally” settle the question of a territorial legislature’s power over slavery. To the Court’s “decision, … whatever this may be,” Buchanan added, I, “in common with all good citizens, …shall cheerfully submit.”

– 4 –

Two days later came the decision. Most northern citizens did not cheerfully submit. Nor did the northern populace cheerfully believe Buchanan’s claim to no prior knowledge of what the Court would decree. But while the president’s dissimulation failed to produce public belief in his noninvolvement, the question remains whether Buchanan’s secret intervention produced the Supreme Court’s verdict. Or to ask the question another way, without the president-elect’s intrusion, would the Court have chosen its less provocative option: reaffirming Missouri’s law?

The possibility that Buchanan turned around the Court’s Scott deliberations hangs on whether Robert Grier would have bowed to the Southern Democrats’ desire, without the president-elect’s note to his fellow Pennsylvanian, and on whether the southern judges would have declared congressional emancipation unconstitutional, without the Yankee jurist’s acquiescence. If Buchanan had not intervened, Grier might have eventually caved in anyway. Alternatively, the southern jurists might have at last dared to move ahead uncomfortably without him. As Grier and Catron both told Buchanan, the recriminations flying around chambers, especially between the Southern Democrats and the northern non-Democrats, were driving the Court in those directions, before the president-elect intervened.

But once before, the Southerners had reluctantly pulled back, when they could not budge Grier or Nelson. Perhaps, after failing again to move Grier, they would have retreated again. If the southern jurists had again decided that going it alone would be counterproductive, perhaps the two northern non-Democrats would have agreed to remain silent on congressional power to emancipate, in exchange for southern agreement to fall silent, too. All those “perhapses” add up to an important possibility. Without James Buchanan’s intervention, there might have been no Dred Scott Decision, as contemporaries came to mislabel, to know, and to hate it.

If Buchanan had defended instead of hidden his perhaps crucial clandestine visit to the judicial domain, he probably would have claimed, as would latter-day presidents, that grave national crises require unprecedented presidential responses, even if such actions momentarily transcend the Founding Fathers’ checks and balances. Buchanan probably would have added that the long-sought panacea of Supreme Court intervention, to silence a question that would otherwise tear apart the republic, legitimated an executive to step on the Court’s terrain, this one time only.

But the unprecedented intervention could be no more legitimate than the assumption that produced it. Buchanan’s assumption that the Republican Party would surrender congressional abolition of slavery in the territories, because a Court controlled by Southern Democrats ordered the surrender, was the wildest illusion. So too, the five Southern Democratic jurists’ assumption that they could make the issue of slavery in the territories magically vanish, if only one or two Northern Democratic jurists would join their magic act, was delusive fantasy. The lesson of the so-called Dred Scott Decision was neither that proslavery perpetualists decreed nor that fire-eating judges paid no heed to Union. Instead, a distressed imminent president and six jurists shared admiration of perpetual Union, qualms about perpetual and unreformed absolute power, and anxiety about northern antislavery attacks, southern fury, and a crashing republic. They thus developed frantic illusions about a paper panacea that could only feed the sectional flames.

– 5 –

The Court’s mode of announcing its verdict was almost as inflammatory as the substance. The provoking appearance of foul play involved not only Buchanan’s dissimulation in his Inaugural Address, not only his whispering with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney on the inauguration stand, but also Taney’s bearing and logic, when he read the Court’s decision on March 6, 1857. The judges had chosen the wrong messenger to convince the nation that their message was right.

The choice of Taney was a natural mistake. The well-known chief justice had led the Court for over a quarter century. Ever since John Marshall’s day, the chief justice had written and read the Court’s most important decisions. This verdict compared in importance with any of Marshall’s.

But however logical the choice of Taney, the Marylander plastered a sour sectional face over a decision meant to produce national smiles. The chief justice, almost eighty years old at this, his most important moment, felt, looked, and acted like a fossil, angry to be discarded. His wife was dead, his children busy, most of his friends perished. The lonely survivor, once a rich lawyer, now struggled on a judge’s salary. And for all his sacrifices, had he received the nation’s adoration, as had his predecessor, the sainted John Marshall? No way. He was widely respected but seldom cherished. Some Washingtonians even dismissed the fading relic as just another Southerner. That meant to many Yankees just another tyrant.

To the bitter Taney, that distortion epitomized all the misunderstanding lately heaped on his sagging shoulders. He had given his life and fortune to the cause of limited constitutional government. He had freed his slaves from his unlimited governance. And holier-than-thous had the presumption to call him tyrant!

With his so-called Dred Scott Decision, the antique threw back every scrap of his scorn. Less than two weeks separated the long-wavering Court’s final, late February turnaround and Taney’s March 6 announcement. During this overly short period, the aging and feeble chief justice often felt too exhausted to write. When his energy fitfully returned, he scribbled frantically, still drafting up to the minute before he delivered his oral opinion, still redrafting his written opinion for weeks thereafter.

That harried, hurried process of composition left no possibility that this angry Southerner’s arguments would calmly distill the Court majority’s opinions. As a result, Taney announced as the Court’s judgment some verdicts that no Court majority had accepted in chambers (for example, that blacks could not be citizens). His rationales also made some of the Court majority squirm. So the other southern judges felt compelled to write socalled concurring opinions, which on some points implicitly dissented. Thus the public heard not one pronouncement but clashing voices. The result: doubt about what had been decreed, and why.

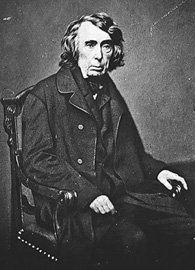

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (left), looking to Northerners and to Harriet and Dred Scott (above) as grimly tyrannical as his proslavery Supreme Court decree sounded. But Taney actually harbored the Maryland unionist and manumission inclinations that worried proslavery perpetualists. Courtesy of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (the Scotts) and the National Archives (Taney).

Taney also dubiously justified his most critical proposition. To argue that Congress could never abolish slavery in the territories, Taney issued an unnecessarily problematic interpretation of the “due process” words in the U.S. Constitution’s Fifth Amendment. That amendment decrees that “no person” shall be deprived of “life, liberty, and property, without due process of law.” As abolitionists interpreted this wording, Congress could give black “persons” their “liberty,” even if slaveholders thereby were deprived of “property,” so long as lawmakers followed a “due process of law.” In his dismissive answer, Taney insisted, with scant explanation, that no congressional “process of law” could validate any seizure of any property, for any purpose whatsoever.16

Judge Peter Daniel, in his concurring argument, developed the more discreet position that Taney barely mentioned. Slavery, Daniel urged, because the only form of property explicitly mentioned in the Constitution (witness the fugitive slave clause), retained special protections against congressional seizure. But by pushing property protection limitlessly beyond Daniel’s limited due process protection, Taney looked all the more to be rationalizing an extremist’s prejudice, not defining a majority consensus.

The man who served up this motley argumentative stew looked as distracted as his reasoning. The elderly jurist’s skin was slack and sallow, his mouth fixed in a sinister frown, his body wrapped in cloths like a mummy’s, his brow shadowed by a descending clump of hair. On March 6, 1857, as the few citizens packed into the tiny Supreme Court chamber strained to hear his words, his voice grew fainter, fainter, then unintelligible. The aged chief seemed the last of some extinct species, squandering his expiring breath in a final defiance of those who dismissed his world as thankfully obsolete.

His reactionary words and his spectral form helped his decision to be misunderstood as fossilized proslavery reaction. But this raging patriarch, still bragging that his own manumitted blacks had proved worthy of freedom, hardly clung to slaves with a death grip. The very great importance of Roger B. Taney was that he could not have flung a more hate-packed decree at the Republicans if he had been a zealot for perpetual enslavement and disunion. So too, the Southerners who made the so-called Dred Scott Decision (and the Border North’s president-elect who begged them to save the Union) could not have better greased the nation’s slide toward disunion if they had been Slave Power ultras.

In this Supreme Court verdict, as in almost all governmental decisions leading toward the battlefield, the Democratic Party commanded a majority of the decision makers; the South commanded a majority in the party; and southern moderates commanded a majority of the Southerners. These ruling moderate slaveholders always feared that northern extremists would provoke southern extremists to disunion, not least because southern nonultras shared ultras’ fury at insulting northern holier-than-thous. So to save the Union, believed many southern foes of disunion, the Union’s government must erect walls against provoking meddlers. So too, to hold calm internal debates about reforming slavery, moderates must sustain blockades against inflammatory outsiders. Yet southern moderates’ barricades, and especially that mother of all barricades, the so-called Dred Scott Decision, always inspired the same outcry from northern moderates: You can exert foul tyranny over blacks, if you must, but you will not tyrannize over your fellow whites—over us.

That was the chorus of Union-smashing voices that shook James Buchanan and his southern Camelot’s attempt at a Union-saving administration, but forty-eight hours into its doomed mission. In the late election, the North’s Republican majority had said in effect to outraged slaveholders: You are criminally immoral, and we will bar you like lepers from expanding into national territories. Now Dred Scott’s southern judges had replied to outraged Republicans: You are criminally foulmouthed, and we hereby ban you from exercising power over slavery in the territories. And at this convulsed moment, with moderates everywhere throwing down gauntlets over who was a pariah, Kansas turmoil swept toward its shattering finale.