CHAPTER 9

The Upper South dream of sending blacks away, having survived the national Missouri Controversy, swiftly faced two local tests. Between 1829 and 1832, twin lower-class challenges threatened the Virginia ruling class. Nat Turner’s slave revolt against slaveholders’ social power, coming almost in lockstep after a nonslaveholder assault on the Slavepower’s political power, led to the most famous southern legislative debate over ending slavery.

Once again, the historical myth is that Virginians surrendered their vision of diffusing slavery away. After successive challenges from white and black underclasses, the upper class supposedly repudiated old apologetics. All southern whites then supposedly hunkered down to perpetuating their newfound blessing.

But Old Virginia could not turn itself instantly modern. While some elitists at the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829 yielded a little to white commoners’ demand for an egalitarian state government, the revised constitution still retained anti-egalitarian power for the Slavepower. Three years later, lower-class resentment plus some upper-class wavering led to a rather close call on a rather wispy legislative resolution to end slavery. But the very slaveholders who saved the institution still voiced hope that blacks and slaves would someday diffuse from Virginia.

1

In 1829, Virginia, like the entire Atlantic Seaboard South, lived under a late eighteenth-century state constitution. The state’s basic laws followed the elitist logic underlying the federal three-fifths clause. Nationally and locally, the late eighteenth-century Anglo-American establishment assumed that those richer and wiser and more virtuous should govern those lesser. The domineering sensibility built into southern slaveholders’ control over blacks here extended into dominance over white citizens as well.

North and South of Virginia along the Altantic Seaboard, whether in Maryland or North Carolina or South Carolina, eighteenth-century constitutions bolstered the elite’s control. White males, to vote, had to possess property. Voters, to hold office, had to possess more property still. Eastern districts, settled first and blackest with slaves, possessed more state legislators than their white population justified. Western districts, settled later and more lily-white, elected fewer representatives than the one-white-man, one-vote formula demanded. Legislatures apportioned according to white numbers plus property—the so-called mixed basis—selected governors and judges. Undemocratic? On the contrary, as ideally republican, according to the eighteenth-century understanding of ideal republics, as the federal three-fifths clause.

As republican ideals shifted from elitist to egalitarian notions, state constitutions were revised too. Constitutional changes came fastest in new states lacking old attitudes and institutions. Alabama, entering the Union in 1819, displayed in its constitution none of the Old Order. In nouveau Alabama, all white males could vote and hold office. The legislature was apportioned on a one-white-man, one-vote basis. The electorate elected governors as well as legislatures. Here was the new herrenvolk order: pure egalitarianism for white males, pure servility for blacks, the constitution itself guarding the color line.1

After 1819, southwestern states copied and perfected the Alabama model. By the mid-1830s, not only Alabama but also Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas were ruled on the one-white-man, one-vote basis. Florida and Louisiana entered the Union on close to the egalitarian republican formula, and Georgia was swiftly approaching that ideal. If all the South had been Alabama, as indeed most of the Lower South was, the Slavepower would have always based its state constitutions and ruling group attitudes on race and never on class.2

But the oldest South was not Alabama. Gentlemen along the Atlantic Coast called unnatural the posture that poor blacks were inferior but poor whites equal to superiors in big white houses. A monocracy, as traditionalists called it, also seemed dangerous. What a way for a master class to master its destiny, to allow another class to master government.

The ranker class, unfortunately for upper-class reactionaries, was swelling inside the oldest South. Nonslaveholding migrants were filling up western Maryland, western North Carolina, western Virginia, and even bits of western South Carolina in the nineteenth century. These Westerners inside the Old East, like immigrants to the New West, wanted egalitarian republicanism for whites. They sought a dismantling of property qualifications for voting and officeholding and an end to malapportioned legislatures. Egalitarians’ pressure moved the Old South slowly towards the New South’s model. But “progress” came only after gentlemen massively fought—sometimes successfully fought—to save their unequal power over whites no less than over blacks.

Fights were most severe and protracted in Virginia. The state’s topography was as if custom-designed to yield pitched battles and uneasy compromises between eighteenth- and nineteenth-century conceptions of republican government. Old Virginia conservatives, located in the middle of the oldest South, were both more intransigent than egalitarians further north and more compromising than elitists further south. Above Virginia, the Maryland gentry showed a weaker devotion to slavery and to the authoritarian values slavery continued to make relevant. Below Virginia, South Carolina commanders retained more entrenched autocratic sensibilities. Virginia’s ancient gentry, producing proportionately more export crops than Marylanders with proportionately fewer slaves than South Carolinians, retained enough outmoded sensibility to provoke newer Virginians. But they were not quite prepared to stonewall against those they provoked.

In addition to being situated too near the middle of the South to attain full extremist consciousness, Virginia’s rulers were too divided from other classes and from each other to consolidate the state’s Old Order. Two mountain chains, the more eastern Blue Ridge and the more western Alleghenies, run parallel to each other, north-south down the Old Dominion. East of the easterly Blue Ridge, sloping south and east towards the Atlantic Ocean, lies the Piedmont and Tidewater. Most counties in this locale of Old Virginia possessed over 40% slaves. At eastern Virginia’s southern extreme, in so-called Southside Virginia, black proportions passed 50%.

West of the westerly Alleghenies, sloping north and west towards the Ohio River, lies the Trans-Allegheny West. Most antebellum counties in this locale possessed under 10% slaves. At its northern extreme, in the so-called Panhandle, western Virginia counties contained only 1 to 5% slaves. Most western Virginians were Pennsylvania Germans or Scotch Irish or other opportunistic Northerners who had lately streamed south through Allegheny Mountain passes. They had seen themselves as going not south but west. They had stopped in Trans-Allegheny Virginia because mountainous terrain invited a free labor rather than slave labor culture. By 1830, few extensively settled portions of the South were so northern, so egalitarian, so free labor, so antithetical, in short, to eighteenth-century elitist sensibilities.

The Valley of Virginia, between the Blue Ridge and Alleghenies, drew settlers from both old supporters and new opponents of fading notions that civic virtue must be imposed from above. Migrants from eastern Virginia, largely of English ancestry, found good prospects for slaveholding in river valleys west of the Blue Ridge. Migrants from western Virginia, often of Scotch or German ancestry, found good conditions for nonslaveholding farming in hilly terrain east of the Alleghenies. The Valley’s resulting slave percentages were in the middling 25% area. Nothing like so massive a neutral zone divided colliding regimes elsewhere in the older South.

The mixed regime in the Valley possessed the balance of power because eastern Virginia, with an unbalanced plurality of constitutional power, lacked the social purity to exert its authority unanimously. Seepage of western attitudes into eastern strongholds went furthest in cities. Here white nonslaveholding laborers, called wage slaves in the proslavery argument, loathed black slaves and resented scornful squires. A rural equivalent existed northwards in eastern Virginia. Northwestern Piedmont and northern Tidewater areas near mountains or near Washington, D.C., possessed fewer slaves and more egalitarian attitudes.

Eastern Virginia attitudes also seeped west, making the newest Virginia as impurely new as Old Virginia was impurely ancient. In the southern Trans-Allegheny, particularly along the Greenbrier River, 25% of inhabitants were enslaved. These rather blackish belts sometimes defended elitist attitudes, unlike whiter, more northern Trans-Allegheny counties. The Panhandle, the most northern area not only of western Virginia but of the whole South, spawned the most uncompromisingly egalitarian version of Virginia republicanism.

Virginia, in short, not only split east/west, with appeasers occupying the Valley between, but also north/south, with compromisers infiltrating uncompromising eastern and western areas. Or to express reactionary vulnerability a more telling way, Virginia stonewallers confronted more than Virginia progressives two mountains and a valley removed. The Old Order also faced faltering views on its own side of the mountain and within its own mansions. Here, as so often, sprawling Virginia was a microcosm of diverse Souths; and here, more than anywhere, the Old Dominion exemplified a southern history not of confident class rule but of division and drift, within and without ruling mansions.3

2

Those mansions—or rather that division about whether leaders ought to live in mansions—epitomized Virginia’s disagreement over proper authority. Homes, to leaders of nineteenth-century folk neighborhoods, were more than dwellings for intimates. Houses were also places to receive non-family folk and, as such, projections of appropriate leadership.

An elitist’s palatial house symbolized a world in which betters ruled lessers of all races. Poorer visitors came to grand mansions with a deferential attitude. An egalitarian’s house, on the other hand, signaled a world where no one dominated. Visitors came to humble huts on equal terms.

Trans-Allegheny leaders’ residences were usually rural log cabins. When leaders lived in cities, in Ohio River towns high in the Panhandle, they resided in the city equivalent, simple brick houses. Unassuming dwellings, whether of rough old logs or shiny new brick, epitomized an unassuming community where comforts were crude and where all (white) folks considered themselves roughly the same.

A visit with an eastern Virginia swell was more like an audience with a lord. The mansions, ancient thick brick relics of English times, stood for lords who had ruled for generations. The first view of these dwellings denoted imposing rulers. Long avenues of ancient oaks, service buildings joined to or near the ancient mansion, the multi-story eminence of the lordly residence—all of this displayed encrusted prerogative. Here some were too rude to be welcome.

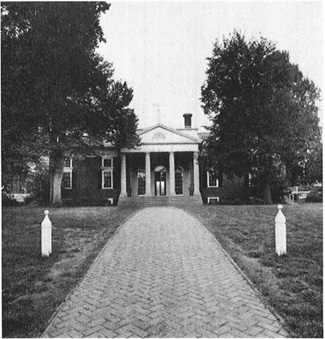

In middle Virginia, the leader’s house epitomized those drifting between elitist and egalitarian regimes. The most notorious drifter was, of course, Thomas Jefferson, and his lovely house exquisitely expressed competing conceptions of how republicans should lead. Anyone who wishes illustration of the middle ground between the state’s eastern and western extremes has only to experience Monticello.4

The word “Monticello,” meaning “little mountain,” expressed in itself a compromise. Jefferson and Monticello were of that eastern Virginia hilly area rising towards western Virginia mountains. Jefferson’s Albemarle County, while containing some 50% slaves, was located in Blue Ridge foothills, leading to regions where few were enslaved. The magnificent view from Monticello, looking over western mountains dominated by nonslaveholders, left Thomas Jefferson no illusions about being able to dictate to egalitarians. At the eastern extreme of Virginia, in contrast, the equally magnificent view from Mount Vernon, looking down on a Potomac River dominated by slaveholders, left the nation’s most famous surveyor every reason to think he could master more worlds than he could survey!

The first view of Mount Vernon, as one enters through endless flat acres, is of a typical eastern Virginia ruling mansion. George Washington’s Georgian expanse stretches from lordly residential quarters toward kitchen, carriage house, smoke house, and other comforts. In contrast, the first impression of Monticello, as one reaches the summit of the little mountain, is confusion about whether the house is lordly. Trick windows create confusion. A three-story palace looks like a single-story home because of windows faked to look as if only one tall floor exists.

Extensions of the residence to each side, because initially invisible, enhance initial impressions of anti-grandeur. A sweeping three-part complex, with paired wings connecting the central living quarters to service units, has been camouflaged to look at first like a one-part house. Jefferson accomplished the trick by placing his service wings underground out front, only visibly above ground out back.

Inside, antebellum servants were almost as invisible as service wings had been in front. Instead of blacks cleaning, cooking, and scurrying underfoot, in the normal way of southern grandeur, the residence seemed reserved for self-sufficient whites. Trick devices, not slaves, connected residents with comforts. No liveried servant opened the paired doors. Instead, the pressure of a visitor’s hand on one also opened the other. No slave brought food or drink. Instead, pivoting windows delivered treats. It was as if some magician had created not a showpiece for slavery but a democrat hiding slaves.

The overall effect was less of magical contrivance than of aristocratic slaveholder and egalitarian republican affecting a balance. Nowhere else in the South could one find such aristocratic hauteur seeking such democratic simplicity, such a luxuriously pampered squire served by so many invisible slaves, such imposing decoration affecting commonplace use. The secret of straddling the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as expressed in the bricks and mortar and especially the trick windows of Monticello, was to be seen as somehow above, yet somewhat of the masses. Jefferson, who lived closer to American nonslaveholders than did most Virginia titans, wished to be seen as a personage both superior and equal. His house announced a host who humbly heard—and who imperiously instructed too.

Monticello and its trick windows. Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, Inc./James Tkatch.

So strained an amalgam was easier to announce in trick windows than in straightforward prose. Jefferson’s political theory was a labyrinth seeking a juncture between warring viewpoints. Not for him was the straightforward, class-infested ideology of eighteenth-century elitist republicans to Monticello’s east, who based upper-class prerogative on denial of human equality, white or black. Nor was he ready for the straightforward, race-infested ideology of nineteenth-century slaveholders to Virginia’s west, who used the color line to reconcile white egalitarianism with black inequality. Jefferson, ever in between, erected his political ideology, like his mansion, on the foundation that white equality was truth—and error too.

He began where more reactionary Virginians ended, with the concept of a natural aristocracy. As a domineering slaveholder raised in a century presuming that the propertied must dominate, he believed enlightened gentlemen must control enlightened government. The best should rule, dispersing civic virtue. The worst should follow, lest civic vice predominate. Orthodox eastern Virginia opinion, all of that.

Where he broke with easterly fossils—where he edged towards neighboring newcomers—was in assuming that commoners had sufficient civic virtue to select governors. No need to assure reign of natural aristocrats by disenfranchising and gerrymandering. Lessers would elect right superiors. Then inferiors would defer.5

The potential flaw in that formulation—the place Jefferson’s natural aristocracy unnaturally deviated from the aristocratic lesson of slavery—was that superiors’ wise government depended on inferiors’ wisdom. Lessers must be wise enough to elect right superiors. Much of the balanced Mr. Jefferson’s unbalanced temper stemmed from awareness of that flaw. He feared that his Federalist opponents’ demagoguery would render his trusted electorate untrustworthy. Aristocratic uneasiness led to Jefferson’s darker record on civil liberties, including advocating laws against “seditious” libel. Books were also known to be censored at the University of Virginia, which he founded.6 But while this aristocrat occasionally sought to jail dissenters and screen information, he never sanctioned Virginia’s undemocratic electorate and unrepresentative legislature. He called Virginia’s eighteenth-century constitution, giving some men unequal privileges, “a gross departure from genuine republican canons.”7

Further eastward, Virginia squires considered Jefferson’s attack a gross departure from responsible class domination. Not for them were tricks making a superior’s palace less palatial. Nor would they tolerate Jefferson’s concern over whether inferiors really would elect the right superiors. They would not give inferiors the chance to fail. They would ensure the reign of the best in the constitution—unless compromised by faltering leaders inside more northern and more western Piedmont regions.

3

Statistics illustrate how a Virginia constitution half a century old was, despite Jefferson, perpetuating an eighteenth-century regime thirty years into the nineteenth century. By 1830, the old suffrage requirement of owning 50 acres or an equivalent still disenfranchised perhaps half of Virginia’s adult white males. The anti-egalitarian apportionment of the tax-initiating lower house also still gave extra power to Virginia’s eastern establishment. In the 1820s, the first Virginia, the encrusted Tidewater, with but 26% of the white population, had 35% of Virginia’s lower house delegates. At the same time, Virginians come lately in the Valley and Trans-Allegheny, with 44% of the white population, had only 37% of the delegates. These disproportions in Virginia’s House of Delegates paralleled disproportions in the national House of Representatives, product of that elitist relic, the three-fifths clause.8

The Slavepower had still more disproportionate power, in Virginia as in the federal government, in the upper house. Locally as nationally, however, an eighteenth-century Slavepower with some extra power possessed nothing like absolute sway. Virginia’s slaveholding elite had only enough undemocratic power to save itself in close legislative votes—and to irritate egalitarian republicans mightily.

As the nineteenth century progressed, population movement made the Slavepower’s undemocratic share of power ever more irritatingly anti-republican. The Tidewater experienced almost zero population growth in the nineteenth century. The Trans-Allegheny, with a 500% growth rate between 1790 and 1830, grew faster than all other parts of the state put together. Thus the Trans-Allegheny, possessing less than half the Tidewater’s white population in 1810, had 10% more white inhabitants by 1829—and a frozen two-thirds fewer lower house delegates.

That slide away from one-white-man, one-vote republicanism led increasingly irate Westerners to demand a constitutional convention throughout the 1820s. By the end of the decade, Easterners sought to ease pressure by a concession meant to concede little. The eastern legislative majority sanctioned a popular vote on whether to call a convention. But the popular vote would poll an undemocratic populace, since only half of white male adults could vote. Should the people approve constitutional reconsideration, the malapportioned legislature could malapportion convention seats.

The people approved for a reason ominous to the Old Order. Eastern Virginia, with the votes to block a convention, lost because some of its own defected. One-fourth of Tidewater voters, heavily in cities peopled heavily by jealous nonslaveholders, voted for reconsideration of elitist republicanism. More important, 45% of Piedmont voters, largely in Jefferson’s northwestern Piedmont, defected from eastern reactionaries. A unanimous Tidewater and Piedmont could have defeated the convention call by approximately 24,000 to 15,000. Instead, the referendum won, 21,896 to 16,632.

When the legislature voted on convention apportionment, the northwestern Piedmont’s representatives again defected to give the East a few less convention than legislative seats. But the few elitist defectors stopped short of voting for an altogether egalitarian convention. Eastern Virginia was awarded nine more delegates than its white population warranted. Easterners, with a bare majority of Virginia whites, would have a swollen two-thirds’ majority of the Convention.9Eastern oligarchs could still save the Old Order—if they could straighten out gentlemen’s confusion about how gentlemen should dominate.

4

Easterners and Westerners descended on Richmond for the Convention of 1829 as if dressed for war between Old and New orders. The eastern old guard—Monroe, Madison, John Randolph of Roanoke, Benjamin Watkins Leigh—bore the look of eighteenth-century drawing rooms. Their white wigs were scrupulously powdered. Their velvet cravats were fastidiously tied. Their knee britches and silk stockings were meticulously married. When their lordly leader, John Randolph of Roanoke, descended to endure the Convention, he came down from his imported English coach drawn by his imported English horses, snapping open his imported English watch to make sure he would suffer no extra moments among the riff-raff.

Randolph smirked at the opposition. Westerners arrived not fit to ride to hounds but fitted out for nineteenth-century enterprise. Their heads were topped with hair crudely cut. Their string ties were askew. Their homespun coats and pants were mismatched. They crudely dismounted from rudely bred horses and tramped on into the Convention.

Old-fashioned squires found noises emanating from trampers as boorish as the sight. United States Congressman Phillip Doddridge, leader of western reformers, sounded to tittering gentlemen like he belonged back in Scotland. Doddridge’s Scotch Irish twang seemed proof that gauche upstarts now presumed to tell Virginia’s first families what Virginia’s traditions involved.

Doddridge spoke for the newest North come to reside within the oldest South. The enterprising attorney, born and educated in Pennsylvania and scion of immigrant parents, had settled in the Ohio River town of Wellsburg, high in the Virginia Panhandle. His new neighborhood was as far north as Philadelphia. His neighbors were usually as little disposed as Philadelphians to own slaves.

But Doddridge was no more Yankee than that huge fourth of the South which cared more about other priorities than slavery. Like so many borderites, Doddridge had no intention of stripping slaveholders of black slaves, unless gentlemen stripped commoners of white egalitarianism. Mountaineers cared little, most of them, whether gentlemen owned “niggers.” They cared passionately, all of them, whether democratic Union was perpetuated and whether state government was democratic. Geographically isolated from Southerners who thought the enslaved South the only South, socially allied with Northerners who thought egalitarian republicans the truest Americans, theirs were priorities which slaveholding reactionaries considered insidiously anti-southern.

At the Convention, Phillip Doddridge’s oration struck reactionaries as proof of commitments askew. Slaveholders, marveled Doddridge, would “exalt a minority into rule, and require a majority of free citizens to submit.” Such slave-holding “doctrine makes me a slave.” No matter if Doddridge could “pursue my own business and obey my own inclinations.” If “you hold political dominion over me, I am” in chains.

Doddridge claimed he sought only to snap chains ensnaring whites. But his language hinted at someday breaking all men’s bonds. Doddridge sought to allay eastern gentlemen’s “uneasiness, in some degree,” on western distaste for slavery. Although he had “no desire to see the slave population of my country increase,” he predicted that slaves would be sold, “to some extent, in western Virginia.”

Easterners compared Doddridge’s “some degrees” and “some extents” and “no desires” with his unconditional desire for western power over the East. In 1790, pointed out the Westerner, the area of Virginia east of the Blue Ridge had contained 186,000 more whites than the area west. In 1829, the East’s white majority had shrunk to 43,000. The majority, Doddridge declared, would “soon” reside westward “and there increase forever.” Westerners were the new Virginia. But outmoded Virginians sought “our perpetual slavery.” Well, “feeble” slaveholders had better not risk our “violence,” warned this non-Cuffee. “A race is rising up” west, “with astonishing rapidity, sufficiently strong and powerful to burst assunder any chain by which you may attempt to bind them, with as much ease as the thread parts in a candle blaze.”10

If anything could enrage supposed masters more than images of hapless slaveholders consumed in flames, it was a supposed friend urging helpless surrender. Chapman Johnson, a slaveholding Richmond lawyer representing a Valley county near Thomas Jefferson’s little mountain, resurrected the specter of a besieged class divided against itself. Johnson urged imperial slaveholders to save black slavery by surrendering white imperiousness.

The Valley representative called western opposition to slavery still only potential. Blocking western priorities would make western antislavery actual. Gentlemen must not dare, warned Johnson, openly avow and adopt “as a principle of your Constitution” that Westerners “must pay for the protection of your slaves” with “the surrender of their power.” You would then hand your strongest potential enemies “the strongest of possible temptations to make constant war” upon you.

The war would be more one-sided, gloomed Chapman Johnson, than stagnating East against vigorous West. True, the area west of the Blue Ridge would soon contain the white majority. But even worse, western enemies would find “many ardent auxiliaries in the bosom of your own society. Eastern white menials, owning none of that property, and doomed to the laborious offices of life,” feel themselves degraded when laboring “in common with the slave.” White wage slaves also harbor a “sentiment of envy towards” slaveholders. East and west, concluded Johnson, a nonslaveholder majority which cared more about white egalitarianism than about black slavery should be given the racist regime it wants. Then you will “inspire a feeling of affection—and justice.”11

Johnson here championed a classic minority strategy when a majority still remained only potentially an enemy. Johnson would soothe, appease, avoid awakening hostility. Like southern appeasers to follow, Johnson conceived that actions intolerable to majorities would drive egalitarians towards antislavery. Johnson was for utopia, herrenvolk Alabama style: sheer democracy for whites, sheer despotism for blacks, no crossing over the color line.

The classic alternative minority strategy, that the few must dominate not through appeasement but by dictation, had three brilliant advocates in the 1829 Convention: Benjamin Watkins Leigh, John Randolph of Roanoke, and Judge Abel P. Upshur. The trio remained convinced that the powerful had always, would always, and should always command. Their stonewalling strategy, like that of reactionaries for the next 30 years, required the upper class to come to full consciousness and to stop a potential antislavery majority from realizing a countervailing consciousness. Tidewater reactionaries favored utopia, anti-herrenvolk South Carolina style: elitist republicans dominating poorer folk, black and white.12

Stonewalling had to begin with a minority convinced that majority rule was wrong. To Randolph, the “principle that Numbers and Numbers alone, are to regulate all things” was “monstrous tyranny.” Majority rule was, in Leigh’s words, “the end of free government.”

None of the trio could see natural or rightful reason for the herd to rule the herdsman. In a state of nature, they pointed out, a few powerful beasts “naturally” prey on those weaker. The powerful would not be so unnatural as to enter society to be preyed on by the powerless. Rather, “those who have the greatest stake” of social wealth must possess “the greatest share” of political power. Benjamin Leigh had none of Thomas Jefferson’s nervous faith that the rabble would elect proper aristocrats. Power given unnaturally to the mob would result in demagoguery, “corruption,” “violence,” ending “in military despotism. All the Republics in the world have died this death.”13

A viable republic must ensure the constitutional rule of the civically virtuous—alias legal reign of the wealthy. White “peasants,” no less than black, must accept their betters’ rule. Not that the “hardy peasantry of the mountains” are comparable to black slaves, Leigh condescendingly conceded, “in intellectual power, in moral worth, in all that “raises man” above the brute…. But I ask gentlemen to say,” Leigh sniffed, whether those “obliged to depend on their daily labor for daily subsistence, can, or do ever enter into political affairs. They never do—never will—never can…. So far as mind is concerned,” the “peasantry of the west” lacked capacity to govern.14

Peasantry of the West. How that contempt did enrage egalitarian republicans such as Phillip Doddridge. How Leigh did delight in their outrage. At that pristine moment of hatred, grandees and commoners knew what history would take 30 more years to reveal—that Virginia, the pivotal state in the middle of the South, could not forever find a middle way.

The extremes already preferred separation to submission. Doddridge conceived that gentlemen’s “immoral” denial that we are “your equals in intelligence and virtue” and their “corrupt” demand that government confer “power … on wealth” ought to create a new 1776. Randolph believed that the mob’s nonsense that “a bare majority may plunder the minority” and their “demand to divorce property from power” would fashion “a new despotism.” Were he but mercifully younger, squeaked the aging relic, “I would, in case this monstrous tyranny shall be imposed upon us, do what a few years ago I should have thought parricidal. I would withdraw from your jurisdiction. I would not live under King Numbers.”15

The worst “stupidity” an enemy of King Numbers had to endure in the Convention, Randolph added, was Chapman Johnson’s nonsense that the East’s “unnecessary” attacks on majority rule created the West’s “unnecessary” attacks on minority enslavement. Rather, rival social structures necessarily produced rival political ideologies. Just as the East’s aristocratic politics grew out of an aristocratic institution, so the West’s egalitarian politics grew out of an egalitarian culture. The very “habits” of yeoman culture, added Upshur, especially the “personal exertion” of the individual free to make his own world, created “a rooted antipathy” to inequality, both social and political. Surrender the war for political inequality and a war against social inequality would follow.16

Easterners expected the war to begin as battle over taxation and appropriations. Westerners believed that mountains blocked western prosperity. Build canals and roads through the towering ranges, so conceived isolated Appalachian laborers, and free labor markets would absorb mountaineers’ products. State internal improvements could liberate free labor energies.

Benjamin Watkins Leigh answered that nonslaveholders would then enslave the rich. The mob would finance its roads and canals by passing soak-the-slave-holders taxation. Nor would slaveholders’ enslavement end with towering taxes on slaves. “Oppressive taxation,” a critical “interference” with “our slave property,” would lead to the ultimate interference. “When men’s minds once take this direction, they pursue it as steadily as man pursues his course to the grave.”17

When men’s minds take this direction. Benjamin Leigh’s words echoed Chapman Johnson’s diagnosis of “the enemy.” For all Leigh’s talk of war of worlds, he saw no enemy mentality absolutely committed to antislavery. He saw the same phenomenon Johnson spotted—an egalitarian world with tendencies, still unknown even to itself, to perpetuate egalitarianism by abolishing slavery. Johnson, by appeasing on the matter of white rule, would keep that other mind from awakening to its tendencies against black despotism. Leigh, by stonewalling on legislative power, would bring his class to full elitist consciousness and block that other class from evolving towards a countervailing consciousness. Johnson, like southern moderates in coming decades, preferred to ignore tendencies only implicit. Leigh, like southern extremists in years ahead, preferred to assault implicit tendencies at the threshold.

But a minority class stonewalling at the threshold must be a class, awakened and consolidated. Chapman Johnson was right that a minority barring majority rule had better possess overweening determination, now and at all future conventions, to crush what it stirred up. Since the upper class still controlled a malapportioned legislature, and malapportioned legislatures could malapportion conventions, and malapportioned conventions could malapportion legislatures, the ruling class had perpetual theoretical power—if it thought and acted like a class. But let the class crack, Randolph warned, and ‘“the waters are out” and “a rat hole will let in the ocean.”18

Upper-class consciousness was not up to the requirements. One trouble, diagnosed stonewallers, was that geographic priorities transcended class priorities. “The slaveholder of the East,” regretted Abel P. Upshur, “cannot calculate on the cooperation of the slaveholder West, in any measure calculated to protect that species of property.” On the issue of taxing slaves to build western roads, for example, the western slaveholder would discover he was more Westerner than slaveholder. Only in eastern Virginia did slaves “constitute the leading and most important interest.”19

To Upshur’s picture of a class geographically divided in priorities East from West, Randolph added a portrait of slaveholders divided against themselves even in the East. One-white-man, one-vote fanaticism, said Randolph, was a sword above gentlemen’s necks. And “from what quarter” does the swordsman come? “From the corn and oat growers on the Eastern Shore? … From the fishermen on the Chesapeake? The pilots of Elizabeth City? No, Sir, from ourselves—from the great slaveholding and tobacco planting districts!” Randolph professed he never would have believed that Chapman Johnson or any “slaveholder of Virginia” would display “so great a degree of infatuation.”20

John Randolph of Roanoke, one of the nation’s most famous Jeffersonian Republicans, was surely faking surprise that an upper-class compromiser had surfaced. The reactionary chose not to tell the Convention that Piedmont deviations from the gospel of malapportioned legislatures were Thomas Jefferson reemerged. Randolph also chose not to say that he and delegates more toughminded than Jefferson on authority over whites were Jeffersonian softhearts on authority over blacks. Benjamin Leigh confessed to the Convention he wished he “had been born in a land where domestic and negro slavery is unknown.” Heaven forbid he had been nurtured outside of Mother Virginia. But he wished Providence had spared “my country [i.e. his state!] this moral and political evil.”21

Abel P. Upshur was at no less pains to assure his friends that “I abhor slavery.” Upshur would leave termination of the abhorrent, he privately wrote, “to the slow operation of moral causes.” But since termination of bondage must not “be suddenly effected,” he “would not make” legislative emancipation “possible in our Constitution.” As for John Randolph of Roanoke, his secret last will and testament offered freedom to his slaves.22

An impartial observer, hearing Leigh’s public apologetics or spying on Upshur’s private confessions or reading Randolph’s will, had to wonder whether rulers sorry about the slaveholding foundation of superior power would always wage all-out war for prerogative. The hidebound Mr. Leigh, the sneering Mr. Upshur, and the ferocious Mr. Randolph were tougher fighters for authoritarian views than were Thomas Jefferson or Chapman Johnson or any leader of Old Maryland and Old Delaware up north. But the toughest Virginian was compromised compared with Carolinians further south—and he was facing a more uncompromising egalitarian challenge. Was any Virginian, was any ruling establishment in the Upper South, tough enough to stonewall against Chapman Johnson’s appeasements?

The Convention’s ballots showed, as Randolph feared, that too many authoritarians favored surrender of authority. Too many Chapman Johnsons, based too securely in Thomas Jefferson’s northwestern Piedmont, would appease the new egalitarians rather than stonewall for ancient elitism. The key vote came on Leigh’s proposal to structure the tax-initiating lower house on the “mixed” basis of property and numbers. Leigh’s formula, basing a district’s legislative apportionment equally on numbers of whites residing and dollars of taxes paid, would have given the Tidewater and Piedmont, with 54% of whites in 1830, control over 65% of the tax-initiating House of Delegates. Leigh’s mixed basis formula lost, 49–47. Defeat came because 13 Easterners, largely northwestern Piedmont delegates and including representatives from Jefferson’s Albemarle County, deserted to join unanimous Valley and Trans-Allegheny contingents.23

With property knocked out of Leigh’s property-plus-numbers formula, the question became when the numbers would be counted. Since western white population was growing proportionately faster than eastern, Westerners wanted the Convention of 1829 to base apportionment on the 1830 census. Egalitarians also wanted periodic reapportionment, so that the West’s share of legislative seats would periodically increase with its white numbers. Reactionaries demanded apportionment based on the 1820 census and no reapportionment thereafter.

The East won this round because the upper class acted slightly more like a class. Apportionment based on 1820 won over 1830 when three of the 13 Easterners who had defected to defeat Leigh’s mixed basis returned to uphold apportionment based on outmoded numbers. Phillip Doddridge’s motion to reapportion in 1840 also barely lost, this time because one of the 13 eastern defectors wished to freeze apportionment on the unequal 1820 basis.

The 13 eastern wanderers ultimately secured something of a compromise. Where Leigh’s mixed basis of property and numbers would have given the Tidewater and Piedmont 65% of lower house delegates, and an apportionment based on 1830 numbers would have given the slaveholders’ region 54%, apportionment based on 1820 numbers gave the Slavepower 57%. Democratic despots, as usual, were despotic enough to enrage, too democratic to mash those enraged.24

Egalitarian Virginians raged primarily about an ever more elitist future. The defeat of future reapportionment left political power frozen to a formula already nine years anachronistic and sure to grow ever more anti-egalitarian. Such perpetual Slavepower, Doddridge warned, looks to freemen’s “perpetual slavery.”25

Other Convention compromises, Doddridge believed, also enslaved whites. The requirement that voters must have $50 worth of land was neither eliminated, as the West wished, nor kept sacrosanct, as the East desired. Instead, the $50 was reduced to $25, reducing the disenfranchised from about half to about a third of white freemen. The upper house would remain even less democratically apportioned than the lower. The two malapportioned legislative houses would continue to elect state executive and judicial officials.

Westerners went away muttering that white democracy and black slavery were incompatible. Easterners went away wondering whether rulers divided and apologetic about their authority could survive anti-authoritarian opposition. A thousand days later, Nat Turner would press another test of upper-class resolve—and white nonslaveholders would add the most searching test yet.