FROM the earliest times, the construction of physical defences produced a new form of warfare, the siege. Evidence from Crickley Hill, Gloucestershire, suggests that its ramparts, c.2800 BC, were assaulted and burnt down using fire arrows. Prehistoric defences were designed to protect large areas within which communities lived. But at their heart was the desire of an elite to defend its own interests, generally power and wealth. These early fortifications were based on a simple line, or lines, of defence, exploiting height and depth through a series of banks and ditches. These became more complex over time, incorporating the developed defensive ideas seen at the western entrance of Maiden Castle, Dorset, where those attacking were channelled along well-protected ‘corridors’ between the built-up defences. Echoes of these prehistoric measures—the simple circuit of defences surrounding large communities—can be found in the urban enceintes of the Roman Empire. In the political vacuum created by the retreat of Roman power, archaeological evidence also shows that such hillforts were reoccupied in the early medieval period. Clearly there was a continuity of defensive practice linking the prehistoric hillfort with medieval town walls.

But the middle ages also saw a break from this tradition with the emergence of the private defence or ‘castle’. The pretence of defence for all was lost: castles were the unambiguous statements of powerful figures that they were prepared to invest heavily in fortifications to defend their own interests. The proliferation of these smaller defences, seldom covering more than a few acres, complicated the way war was waged. With more fortifications in the landscape, the siege began to predominate as the most effective style of warfare. Few campaigns were waged during the period 800–1450 without siege being laid to at least one, and sometimes several, key strongholds. Only where societies relied less on castles, for example in twelfth-century Ireland or thirteenth-century Wales, did siege warfare remain of secondary importance. Sieges far outnumber pitched battles, naval skirmishes, mounted raids, and all other forms of warfare during the period. Geoffrey V of Anjou conquered Normandy without a battle between 1135 and 1145 and the great warrior King Richard I, although constantly engaged in siege warfare during his ten-year reign, fought no more than two or three battles. Crusades were won and lost through the combination of major siege operations and pitched battle. In thirteenth-century Germany, the wars of succession after the death of Emperor Henry VI, the final struggle with the papacy, and the conflicts caused by the demise of the Hohenstaufen dynasty were all conducted primarily through siege action. Equally, the Christian reconquest of Moorish Spain culminated at large urban centres like Cordoba and Seville. Yet despite the relative frequency of siege action, and the scale of such operations, it was rare for the conclusion of an individual siege, either successful capture or defence, to dictate the outcome of a wider conflict. Striking exceptions can be found such as King Stephen’s success at Faringdon in 1145 which marked the end of civil war with Mathilda, and the English success at the siege of Calais in 1347 which decided much more than the preceding battle at Crécy. Battle in open country remained the stage on which dynastic power could and did change hands. More often than not, however, the preliminaries to battle can be found in a single siege or in a series of military blockades, for example the battle of Lincoln during the reign of Stephen where the king himself was captured. It is clear that the stakes were higher in battle. Sieges could be actively sought, while battle was to be avoided until absolutely necessary. Nevertheless, siege brought the warring parties together and was often used, both wittingly and unwittingly, as the catalyst for decisive military action, the set-piece battle.

A castle or town under siege played a defensive role, but castles also fulfilled important offensive roles too. As operational bases for mobile forces, strongholds acted as supply bases and safe-havens for troops not actively engaged in the field. Broad areas were dominated from these places. The chronicler Suger reported that when the castle of Le Puiset—captured by King Louis VI in 1111—was under enemy control, no one dared approach within eight or ten miles of the place for fear of attack from the garrison. Capture of such threatening redoubts often meant mobilizing large field armies. Conversely, retaining control of these places became the paramount concern of those on the defensive. Aside from their military role, these fortifications also represented political power. They were administrative centres for public authorities, as well as for private lordship, where fealty was rendered and services performed. Castles became the symbols of the wealth, status, and power of those who built them. While maintaining a military function, castles were adapted over time to provide comfortable, even luxurious, accommodation for their lords; at Orford, Suffolk, for example, the twelfth-century keep was split into small rooms, and a gravity-powered water system provided a constant running supply. Dover had similar ‘modern’ amenities. These non-military provisions have led some scholars recently to reassess and reduce the military role of the castle (see also Chapter 5, p. 103). While certainly in part residential, their capacity to withstand siege warns against interpretations which totally ignore their military design. The functions of fortified towns were equally complex, constructed not only to defend the local population, but also to represent the town’s political maturity, and most importantly to protect its economic interests. All three elements can be seen in the construction of walls around the Italian city-states. With such potentially rich pickings in towns and cities, it is easy to see why the siege was attractive to any aggressor.

In military terms at least, the design of defensive structures in Western Europe responded to the menace posed by aggressive forces, both real and perceived, whether it be the small Viking raids or large royal armies, classical siege engines or gunpowder weaponry. Siegecraft was developed to overcome defensive obstacles, from the simplest earth and timber castle to complex multi-layered stone defences. Because of their relative scale, it was easier, quicker, and less costly to adapt weaponry and siege engines than static defences. Fortifications were to play a continuous game of catch-up throughout the period, teetering on the brink of obsolescence, as military architects sought to counter the ever-changing arsenal of the aggressor. The fine balance between defensive structures and offensive weaponry characterizes the period. In actual fact few fortifications fell as a result of direct bombardment or assault. Far more surrendered due to human frailty as supplies ran low, or because relieving forces failed to come to a garrison’s aid. As Robert Blondel commented in fifteenth-century Normandy, ‘It is not by walls that a country is defended, but by the courage of its soldiers.’ Still more strongholds, anticipating siege action, capitulated before siege was laid. The capture of Alençon in 1417 precipitated the surrender of six lesser towns and castles within a fortnight. In the same fashion, the vast majority of English-held castles in Normandy between 1449 and 1450 capitulated without resistance when faced with the overwhelming firepower of the French artillery train. In the main, however, defences appear to have kept pace with changes in weaponry. William of Holland, for example, undertook thirteen sieges between 1249 and 1251, of which only three were successfully concluded. Even a reluctance to change and adopt radically new defensive measures, notably after the introduction of the cannon, failed to prove terminal for traditional defences. Henry V’s conquest of Normandy between 1417–19 was conducted through a series of sieges yet the defences of Caen, Falaise, Cherbourg, and Rouen, all built without consideration for cannon, were able to offer stiff resistance, the last for more than six months. Despite their knowledge of the potency of such weaponry, neither Henry V nor Henry VI redesigned any fortifications after the conquest of Normandy, suggesting that they considered these fortifications capable of withstanding the new firepower. The early incorporation of cannon into the defences of Western Europe, it can be argued, actually made these defences stronger than before. Embrasures for cannon were added to existing defences, for example along the south coast of England, where castles such as Carisbrooke, on the Isle of Wight, and towns such as Southampton incorporated gun loops into their design from the 1360s. By the 1390s most English fortifications were designed to take cannon, as Cooling and Bodiam castles, and the town defences of Canterbury and Winchester show. It is dangerous to assume, however, that all advantage lay with those who defended fortified places. Throughout the period if the besieger could bring to bear the whole suite of aggressive tactics—bombardment, assault, mining, and blockade–few castles or town defences were able to withstand the onslaught for long. Even the best designed castles, those described by contemporaries as ‘impregnable’, for example Château-Gaillard, or Crac des Chevaliers, or Cherbourg rarely lived up to their reputation. Duke William of Normandy was said never to have failed to take a castle.

It is widely accepted that the proliferation of castle building and other defensive works from around AD 1000 had its roots in fundamental social change. This was brought about, in part at least, by the external military threat of Viking, Magyar, and Saracen raids. The marauders posed serious problems, since they were able to move swiftly, either on horseback or by following rivers, to penetrate deep into the heart of Europe. Raiders moved with impunity across the countryside. The only means of slowing their progress was to build defences. Across Europe the threat was the same, but the defensive solutions adopted differed greatly. Viking raids into Francia encouraged the construction of private defences, for example, in the Charente region, and of public works: Charles the Bald at the assembly of Pitres in 864 ordered fortifications to be raised along the major rivers. Refurbished town defences as at Le Mans and Tours on the Loire, as well as fortified bridges on the Elbe and Seine resulted from this initiative and over the next twenty yearsmuch work was carried out. It proved crucial for the successful defence of Paris in 885–6. In Ireland individual communities erected tall round towers both as refuges and lookout points against the Viking incursions. In England Alfred began to fortify the major population centres, creating an integrated system of defences or burhs, offering protection for the surrounding countryside. Generally a single earthen rampart was thrown up, capped with a wooden palisade, often on a naturally defensible position such as a promontory or within the bend of a river. Access points were protected by gatehouses. Elements of several of these earthwork defences can still be seen, for example at Wareham, Wallingford, and Burpham. To counter the Magyar threat, in Germany, Henry the Fowler (919–36) constructed fortress towns such as Werla, Brandenburg, and Magdeburg. Each fortress comprised a series of fortified enceintes leading to a citadel.

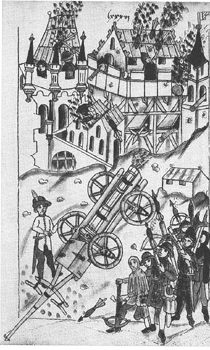

Defence of the Burh. The depiction of masonry defences suggests that the illuminator was influenced by classic images of siege. Some Roman defences were re-used for example at Chichester and Winchester. To guarantee the security of these locations, rural estates were required to provide both men and money, based on the number of land units as laid down in the text known as Burghal Hideage.

Knowledge of how siege was conducted in antiquity was applied, with slight modification, to early medieval siegecraft. Accounts of early sieges demonstrate that, in attack and defence, little had changed. At the siege of Barcelona in 800–1, the Moors burnt the surrounding countryside to deny their Frankish besiegers supplies and took Christian hostages. The walls were weakened by mining and bombardment from stone-throwing siege engines such as petraries and mangonels which used torsion to provide the power tolaunch their projectiles. It also appears that the gates were attacked with battering rams. The final assault was led by men approaching the walls under cover, the testudo (or ‘tortoise,’ an armoured roof on rollers), and the walls were scaled by means of siege towers and ladders. It is clear from this account that diverse measures had been taken in advance of the siege. Such preparation was clearly ordered in Charlemagne’s Capitulare Aquisgaranense of 813 which provided for the organization of trains for siegeworks and the supply of the besieging army. The Capitulare also decreed that men should be equipped with pickaxes, hatchets, and iron-tipped stakes to make siege works. The attack on Paris during the winter of 885–6 illustrates well the state of ninth-century siegecraft. Faced with formidable defences, the Vikings were cognizant of all the methods to overcome them. According to the monk Abbo, they used bores to remove stones from the walls, mined the towers, brought up rams to batter the walls but were unable to bring their siege towers close to the walls, and used fireships to overcome the fortifications on the river. These attacks were repulsed by the defenders of the city with boiling liquids, antipersonnel darts and bolts from ballistae, and forked beams to shackle the rams. Rapid repairs were made at night. The variety of siege methods employed, and the defensive tactics used to counter them, are evidence that siegecraft was not in its infancy. The Carolingian success in defending Paris was a rare achievement. Faced by large area fortifications, manned by few trained soldiers, besiegers could generally expect to succeed. The sheer scale of early defences contributed to their weakness. The defensive solution was to reduce the length of the exposed front; this reduction reached its apogee with the castle.

The design of castle defences sought to counter the threat posed by any aggressive force. As siegecraft evolved so too did castle designs. In most cases, therefore, it is possible to link the great changes in military architecture seen between 800 and 1450, albeit with certain time lapses, to the mastery of available siege techniques, to the introduction of new weaponry, or to the exposure to different defensive ideas, many of which came from the East. Of these, perhaps, the last led to the most radical changes, while the first and second encouraged piecemeal, but nevertheless fundamental, improvements. These factors, individually or in combination, lie behind the five main stages of medieval castle design: the replacement of earth-and-timber castles by those constructed in stone; fortifications based around the keep or donjon; the move from square keeps and mural towers to round ones; the adoption of concentric and symmetrical plans; and early attempts to build fortifications both capable of countering and of using gunpowder weaponry.

Two forms of early fortification were commonly adopted: the ringwork and the motte-and-bailey. In origin each was designed to withstand the methods of warfare of the time, possibly inspired to some degree by the fortified winter encampments of the Vikings. At Ghent and Antwerp, for example, later defences were adapted from those first constructed by the Vikings. By retreating behind physical barriers, defenders effectively neutralized the most powerful element in any army—its cavalry. It was impossible for mounted men to breach both walls and ditches. Even when mounted assault was launched, as at Lincoln in 1217, this was probably led more by a misguided sense of honour rather than by any preconceived military advantage this might bring. The ringwork, a simple fortified enclosure of earth and timber, usually surrounding one or two major buildings, offered few other advantages to its defenders. The addition of an elevated motte, utilizing a natural or artificial mound (as much as 20 m high and up to 30 m in diameter at its top), greatly enhanced defensive options. From its dominant position, the enemy could be observed, helping defenders to coordinate their limited resources on areas of the castle which were under attack. It might also provide a platform, such as that found at Abinger, Surrey, from which missiles could be rained down on any besieging force. With a bailey, or series of baileys, livestock and other provisions could be gathered in anticipation of a lengthy siege (rendered the harder if the surrounding countryside was then scorched), while defenders could retreat behind successive lines of defence as they fell, ultimately occupying the motte itself. Quick and easy to construct, this form of fortification was predominant in many parts of Western Europe during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

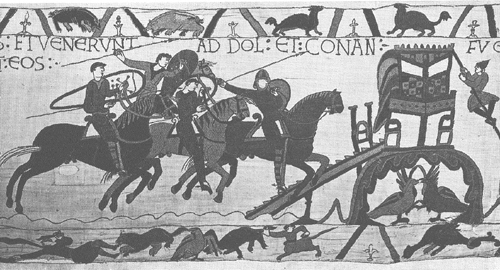

Several castles are shown on the Bayeux Tapestry. It appears that some effort has been made to reproduce a faithful rendering of each castle. Here, the embroiderers have shown the timber tower, the bridge, the gatehouse, and the ditch and counterscarp around the motte in detail. The cavalry charge, however, is probably the result of artistic licence.

As allegiances changed and the political map was in flux there was a need for constant fortification and refortification. Earth and timber defences provided the perfect defensive solution. Their appearance across Europe, from Scandinavia, through the Low Countries, to the Mediterranean proves demonstrably the effectiveness of this defensive design as a military structure. It can be seen also in the introduction of the motte-and-bailey type of fortification into Ireland and Scotland during the twelfth century when stone-built castles were becoming more common elsewhere. Even in areas where the political situation did not dictate speedy construction, it was the motte-and-bailey that was built. From the outset, however, the design of each fortification, while sharing the common features of enclosed bailey and elevated motte, varied from site to site. Hen Domen, Montgomeryshire, the best-studied site in Britain, might be considered classic; its motte surrounded by a ditch occupying one end of a bailey enclosed with its bank and ditch. But of the five castles built during the reign of William I in Sussex, each adopted a different plan: at Hastings the motte was constructed within a prehistoric enclosure, and at Pevensey the medieval fortification was built within the masonry walls of the Roman shore fort; at Lewes it appears that the castle had two mottes, at Arundel the motte was surrounded by two baileys, whilst at Bramber the motte was raised at the centre of one large oval bailey. With such variation in one short period it is impossible to identify any clear evolution of defensive design through time. Evidence also suggests that the ringwork and motte-and-bailey co-existed happily. If on some sites the motte has been shown as a later addition, the motte-and-bailey never replaced the ringwork as the ideal castle plan.

Elsewhere in Europe during the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries other political and social factors such as the emergence of a powerful hereditary aristocracy prompted an unparalleled spread of castles. In Germany unrest in Saxony encouraged Henry IV to construct royal castles but a major cause for castle building here was the anarchy which followed the outbreak of the Investiture Contest in 1075. This led to the construction of castles not only in Germany, but also in Austria, Switzerland, and Italy. These frequently differed from those in France and England. As they were built on land which was not disputed, newly conquered, or immediately under threat, military architects could select the most naturally defensible sites, hilltops and promontories such as Karlstein bei Riechenhall and Rothenburg. Due to their elevated siting, the main defensive feature of these castles was the Bergfried or watchtower, not the motte. Political instability stimulated castle building, as seen in Normandy in the 1050s and in England during Stephen’s reign. Attempts were made to restrict the spread of castles: the Norman Consuetudines et Justicie of 1091 legislated for ducal control over all castle building, prohibiting the erection of fortifications over a certain size and permitting the Duke to enter or demand the render of all castles in his duchy, whether his or not, at will. In fact, the ducal monopoly over building castles harked back to royal rights enshrined in the Carolingian Edict of Pitres; similar claims to rendability were made by other strong rulers during the twelfth and subsequent centuries.

Siegecraft in the eleventh and twelfth centuries varied little from that of earlier periods. Mangonels and ballistae constituted the heavy artillery deployed to weaken any defences. Mining remained an effective tactic since in most cases earth-and-timber fortifications were surrounded by dry, and not water-filled, ditches, allowing miners to approach and undermine outer defences. Assaults were focused on weak points on the outer defensive line such as gates, while relatively low ramparts and timber palisades meant that escalade was a feasible option. More importantly, these fortifications were susceptible to fire. Henry I burnt down the castles of Brionne, Montfort-sur-Risle, and Pont-Audemer, while the Bayeux Tapestry shows attackers setting light to the palisade around the motte at Dinan in 1065. Moreover, unlike the sieges of large cities such as Barcelona or Paris, where the besiegers found difficulty raising the manpower for full blockade, the small size of castles made them vulnerable. An effective method of blockade was to construct counter-castles, from which a relatively small force could survey the besieged castle, preventing the free flow of traffic to and from it, while providing a base from which to launch aerial bombardments, and a place of retreat if the besieged counter-attacked. William I constructed four counter-castles to blockade Rémalard in 1079. In 1088 William II used fortified siege towers against Rochester and in 1095 constructed counter-castles at Bamburgh. Similar tactics were used by Henry I at Arundel and in 1145, during the anarchy of Stephen’s reign, Philip, son of the Earl of Gloucester, advised his father to build counter-castles from which to monitor the sallies of royalists garrisoned at Oxford. Counter-castles continued to be used throughout the period; they were perfected by the mid-fourteenth century. Siege bastilles built around Gironville in 1324–5 were constructed as raised earthen platforms, 35 m square and 2 m high and surrounded by ditches 4 m deep and 12–20 m wide. The English bastilles for the siege of Orléans in 1428–8 were similarly 30 m square and able to contain 350–400 troops within their fortifications.

By the early twelfth century, siege tactics were well understood by most military commanders. As a result, sieges regularly succeeded, prompting the need to find new defensive solutions. The improvement of building techniques, used in the construction of ecclesiastical buildings, were applied for the first time to military buildings. A natural step was to replace earth-and-timber defences with masonry. In terms of defensive options, early stone castles differed little from their wooden predecessors. Defence was still based on the holding of the outer line of defences, now stone walls rather than timber palisades. The donjon either replaced or colonized the motte, offering active defensive options by its elevation, as well as passive resistance as a place of last refuge. The earliest now-surviving stone castles were built in France during the late tenth century. As he expanded his power, Fulk Nerra, count of Anjou (987–1040) constructed castles to protect his possessions against neighbours in Blois, Brittany, and Normandy. Amongst these, Langeais possessed a stone ‘keep’ by 1000, while at Doué-la-Fontaine, an earlier unfortified Carolingian palace was converted into a donjon, but generally Nerra’s castles were at first of the motte-and-bailey type; even amongst the highest ranks in society, initially few could afford to build extensively in stone. Thus most of the earliest stone castles in England and France were either ducal or royal establishments. Of these Rouen, the White Tower in London, and Colchester were precocious examples. But by the 1120s Henry I was reconstructing in stone many of his timber castles in Normandy, including Argentan, Arques-la-Bataille, Caen, Domfront, Falaise, and Vire. All these were dominated by massive square or rectangular keeps; elsewhere great lords, like those of Beaugency or the earls of Oxford (at Castle Heddingham, Essex) followed suit. At Gisors Henry I constructed a shell-keep surrounding the motte; other fine examples also survive at Totnes in Devon and Tamworth, Staffordshire. In Germany, there is evidence at Staufen that a stone tower and masonry walls had been erected by 1090. Castles proliferated in Léon, Castille, and Catalonia. Here, however, Christian conquerors were more often content to add elements such as keeps to earlier Moorish fortifications. Many fortresses remained garrison centres rather than feudal caputs. Despite much castle building, the fortified towns of the peninsula also remained central to defence, with Christian powers preserving the best of Moorish military architecture like the massive town walls and gates of Valencia.

Masonry offered far greater resistance against stone-throwing siege engines inherited from the Roman world. In combination with more extensive and more complex outworks, the threat from mining could be minimized. Masonry castles could expect to withstand siege longer, since mining operations were more difficult. The threat from fire and physical bombardment was diminished. The heightening of walls made escalade more difficult, while improved outworks including flanking towers and gatehouses offered greater cover against attacks on the walls, and water-filled moats prevented siege towers being drawn up against them. Indeed, by the mid-twelfth century even minor castles were able to resist aggressive action for considerable periods. At this period the normal duration of a siege appears to have been between four and six weeks, although there were notable exceptions: the siege of Tonbridge was decided in just two days by William II, while the siege of Norwich in 1075 and the siege of Arundel in 1102 both lasted three months. Stone fortifications, if well-provisioned, were able to withstand siege longer. Louis VI had to besiege Amiens for two years, while it took Geoffrey V of Anjou three years to enter Montreuil-Bellay, a siege notable for the first mention of the use of Greek fire in the West. Time was an important factor, since this greatly increased the chance of relieving forces coming to the assistance of the besieged. Nevertheless, despite all these improvements, the besiegers could proceed along the same lines as before. With force, now technically more difficult, every defensive measure could be overcome. Richard I at Chalus and Frederick Barbarossa at Milan and Tortona used reconnaissance to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the fortresses that they faced. The former made great use of speed in attack to catch strongholds unprepared for siege while the latter, a master of siege warfare, was prepared to build great siege works around large Italian cities to enforce long-term blockade. Many accounts of siege at this period record the filling of wet moats or dry ditches either with rock or rubble, for example at Montreuil-Bellay, or with faggots and timber as at Shrewsbury or Acre.

Falaise. The two classic donjon types, the twelfth-century square keep constructed by Henry I of England and the thirteenth-century circular donjon built by Philip Augustus of France. Not only does this juxtaposition demonstrate the progress made in military architecture, but also hints at how different castle designs could be used for political purposes.

The most important innovation around 1200 was a new form of siege engine, the trebuchet. Unlike the mangonel and ballista, the trebuchet used counterweights. It was more powerful than its predecessors, and more accurate, since by changing the size of the counter or altering the pivotal length, it was possible to vary its range, vital to pinpoint specific targets (see also Chapter 5, p. 109). It has been estimated that a trebuchet could propel a 33 lb casting-stone about 200 yards; it could also be used to throw other missiles, including rotting carcasses, a primitive form of biological warfare. The introduction of the trebuchet shifted the balance of siege in favour of the besieger; they were much in evidence at Toulouse in 1217–18 and the many other sieges that marked the bitterly fought Albigensian Crusade in southern France. The destructive force of any projectile thrown by the trebuchet needed to be addressed if castles were to remain effective against attack. Two counter-measures were taken: increasing the height of the walls, and reducing the number of flat surfaces prone to such bombardment. The rectangular or square donjon was replaced by the round donjon just as square flanking towers were replaced by semi-circular or convex mural towers. By increasing the number of towers, flanking fire could be ranged against anyone approaching the walls. The construction of sloping talus on the walls not only dissipated the power of incoming projectiles but also allowed objects to be dropped from the wall heads which then ricocheted unpredictably towards the attackers. Elsewhere, for example at Château-Gaillard and La Roche Guyon, donjons were constructed to offer an acute peak to the most likely direction of attack. Round towers also offered greater protection against mining. Any angle in a wall proved its weakest point, exploited for example to great effect at the siege of Rochester in 1216. Nevertheless, this siege demonstrated that square keep castles could withstand royal siege; even after the collapse of the corner, the defending garrison believed the tower still to be capable of resistance and it was only the failure of relieving forces to arrive that finally forced surrender.

A number of works detailing different siege-engine designs were produced throughout the thirteenth century, for example Villard de Honnecourt’s sketchbook and Egidio Colonna’s De Regimine Principum. This pulley-system assault tower was designed by Guido da Vigevano at the beginning of the fourteenth century, just one of a number of his innovative military ideas.

Round-towered castles began to be constructed in England and France in the 1130s, for example at Houdan, where the round keep was further strengthened by four round towers which projected from its line, and Etampes, built in the 1140s, designed on a four-leafed plan. Circular donjons only became dominant, however, at the start of the thirteenth century. At the peripheries of Europe, square towers continued to be built; in Ireland, for example the great square keeps of Carrickfergus and Trim were erected between 1180 and 1220. By contrast, Philip Augustus’s re-fortification of Normandy after 1204 saw many square keeps either replaced by round towers or their outer fortifications improved by the addition of semi-circular angle and mural towers as at Caen and Falaise (see p. 173, and cf Trim p. 68). This period saw the introduction of castle forms which did not rely on the strength of the donjon. The Trencavel citadel at Carcassonne and the Louvre were built on a quadrangular plan around small courtyards, defended by towers at each of their four angles, a plan which was to be readopted in fourteenth-century England at Nunney and Bodiam. Similar compact fortifications also emerged in the Low Countries from the thirteenth century. The lack of building stone meant that many were constructed in brick, but exploited the low-lying nature of the land by adding extensive water defences. Muiderslot, built by Count Floris IV provides a good example of these Wasserburgen, a regular castle with projecting circular angle towers and a defended gatehouse totally surrounded by wide moats. At a lower social level, this was also the period when many otherwise lightly defended manor houses acquired water-filled moats.

At the same time that military architects began to understand the defensive worth of circular structures, other defensive ideas began to spread back into Western Europe from the East as the early crusades brought Christian Europe into direct contact with new ideas. Exposure to the massive fortifications at Byzantium and Jerusalem, Nicea with its four miles of walls, 240 towers, and water-filled moat, Antioch with a two-mile enceinte with 400 towers, and Tyre with a triple circuit of walls with mural towers which were said nearly to touch, greatly impressed those that saw and attacked them. The siege of Jerusalem in 1099 demonstrated how difficult these fortifications were to take. The crusaders, after filling the ditches brought up three siege towers to overlook the walls of the city. Savage bombardment failed to breach the defences. Only by scaling the walls and opening one of the town gates was the city finally reduced. Of the castles of the Holy Land the most powerful was Crac des Chevaliers, totally remodelled by the Knights Hospitallers after they acquired it from the Count of Tripoli in 1142 (see plate, pp. 96–7). Its defences were based on a concentric plan with the inner circuit of walls close to and dominating the outer line. Access to the inner citadel was through a highly complex system of twisting corridors and ramps which were overtopped on each side by high walls. Its outer line of walls was protected by regular semi-circular angle towers and deep talus offering great protection against projectiles and mining. Its overall strength derived not only from the man-made defences but the naturally-protected spur it occupied. The influence of crusader castles on the siting and design of Château-Gaillard has been long stated and clearly its triangular châtelet or barbican mirrors the powerful outwork to the south of Crac. Just as German castles had exploited the mountainous terrain, so too did many of the castles of southern France such as Montségur or Puylaurens. The impact of the Crusades, however, became most visible from the 1230s. At this time the great banded walls around Angers were erected, the concentric town defences of Carcassonne were perfected, and the heavily fortified town of Aigues-Mortes was constructed by Louis IX to be the port of embarkation for his crusading exploits. In Britain, ideas on concentric fortification reached their medieval apogee in Wales during Edward I’s castle-building campaigns from 1277 to 1294–5. At Harlech, on an already prominent rocky outcrop, an inner line of defences dominates an outer circuit, with a massive gatehouse facing the easiest access. At Rhuddlan, the inner circuit formed an irregular hexagon, its two shortest sides occupied by two gatehouses, whilst at each angle there was a large circular tower. But Edward’s most remarkable, though unfinished achievement in symmetry was Beaumaris, with two enormously powerful gatehouses protecting an inner bailey with angle towers and further mural towers placed halfway along the curtain. This inner line dominated the outer defences, akin to the defences of Crac. Surrounding marshland and the sea provided natural protection. Against these royal enterprises can be set the de Clare castle of Caerphilly begun in 1268. The inner bailey displays the same attempts at symmetry although more poorly executed. The great strength of Caerphilly, however, derived from a series of complex and unrivalled waterworks which allowed two great lakes to be flooded in times of trouble leaving the castle isolated on a small well-defended island. Where topography dictated the plan, Edward was prepared to build more traditional fortifications such as Conway and Caernarvon, although the octagonal flanking towers of the latter mirrors Byzantium’s urban defences and other features, like the decorations of the walls with banded stonework and the symbolism of the Eagle tower, have been linked with Edward’s ‘imperialist’ ambitions. In Scotland too, some efforts were made to incorporate symmetrical, if not concentric ideas, into new defences, like the triangular plan of the castle of Caerlaverock with its gatehouse protected by twin towers at one apex, famously besieged by Edward I in 1300. Water-filled moats kept the royal siege towers at bay, but battering at the gate, an attempt to mine, and aerial bombardment finally brought the garrison to terms. In the same way, the long sieges of Château-Gaillard in 1203–4 and Crac in 1271 demonstrate the problems these fortifications posed for besiegers, capable of penetrating the outer lines of defences, generally with great loss to personnel and equipment, who were then faced with the challenge of more substantial defences.

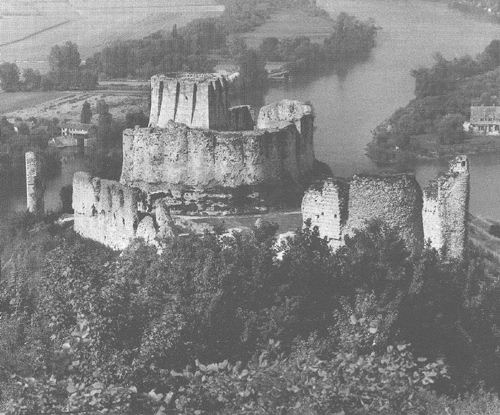

Chateau-Gaillard adopted features probably first encountered during the Crusades. The defences were made up of a series of ditches and walls. If captured the defenders could fall behind successive lines and regroup. The fortifications culminated in an unique wall built of small arcs, more resistant to projectiles, and the donjon, exhibiting enormous machicolations to improve its offensive capabilities.

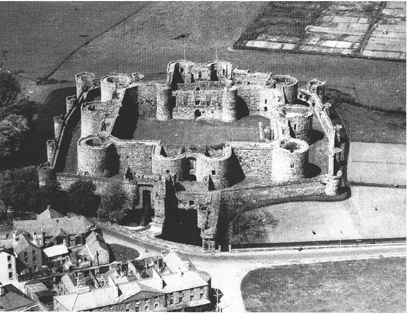

Facing, above: Beaumaris, the perfection of concentric castle design. Its architect Master James of St George fully exploited the firing lines from inner and outer wards to maximize defensive potential. Its strength lay in the powerful gatehouses and complex seaward access. Welsh Edwardian castles form a discrete group, yet each final design was unique, overcoming the problems of local topography and function.

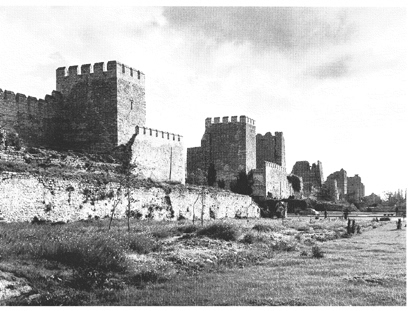

Facing, below: the fortifications at Constantinople were some of the most powerful in Europe. Seen by crusaders they were to exert influence throughout the west. At their height in 1453, there were four miles of landbound walls, nine miles of seaward walls, a vast ditch, and a hundred towers.

The fourteenth century saw few innovations in England and France. Traditional and transitional castles were still constructed; for example, in the Cotentin the polygonal keep at Bricquebec or the reconstructed square keep at St-Sauveur-le-Vicomte, while in England castles became more compact, sometimes known as ‘courtyard’ castles, incorporating water defences in their design. In Spain unrest allowed the nobility to construct further castles, often like Fuensaldana or Penefiel or Medina del Campo based on the square donjon. In Poland and along the Baltic coast, important low-lying brick fortifications were built by the Teutonic Knights between 1291 and 1410, their plan influenced by their monastic concerns, as seen at the most impressive site of Malbork. Here the central cloister was surrounded by a machicolated gallery. Indeed the introduction of machicolations from c.1300, allowing defence from the wall head, marks an important stage in castle design and was widely adopted across Europe. Later, from the last quarter of the fourteenth century other architectural changes stimulated by gunpowder and combustible artillery weapons began to appear. The height of circuit walls was reduced to offer a smaller target to cannon, while the walls themselves were thickened as can be seen in the massive fortifications of southern France, for example Villeneuve-lès-Avignon and Tarascon, and reached their apotheosis in the 13 m thick walls constructed by Louis de Luxembourg, constable of France, at his castle of Ham in the 1470s. In places the whole of the ground-floor was filled with earth to resist the impact of large calibre projectiles. Mural towers were also lowered to the height of the enceinte, and strengthened to act as platforms for defensive artillery pieces. Arrowloops were widened to take the new firearms, characteristically assuming a ‘key-hole’ shape. Further outworks, bulwarks, and bretesches, were perfected, using low banks of earth and timber to protect against artillery, while extra-mural barbicans improved the defensive capabilities of the gatehouse. The impact of these changes and the speed of their adoption, however, should not be exaggerated. They were introduced piecemeal and slowly, to such an extent that no true artillery fortification can be said to have been constructed before 1450.

The beginning of the end. By the late fourteenth century castles such as Bodiam were designed for comfort and effect rather than for purely defensive reasons. Nevertheless an early attempt was made to incorporate firearms into its defences, and the internal arrangement of rooms suggests a realization that the threat from within was as important as that from without.

It appears that cannon were regularly used in sieges from the 1370s. There are some notably precocious examples, such as those used at Berwick in 1333, at Calais in 1347, and at Romorantin in 1356, but these remain exceptional. By 1375, however, the French were able to train 36–40 specially built artillery pieces at the castle of St-Sauveur-le Vicomte. While the potential benefits of bringing firearms to a siege could be enormous, their transport overland and siting caused logistic problems which greatly slowed any advancing force. It was reported in 1431 that 24 horses were required to pull one cannon and a further 30 carts needed to carry the accessories. In 1474, the Sire of Neufchâtel used 51 carts, 267 horses, and 151 men to transport only 12 artillery pieces. Some idea of the speed with which these pieces travelled can be gauged from other contemporary accounts. On average during the fifteenth century large artillery pieces could be moved 12 kilometres per day. In 1433, it took 13 days to take a large cannon from Dijon to Avallon, a distance of 150 kilometres. Others fared worse: in 1409 the large cannon of Auxonne, weighing some 7,700 lb was unable to be moved more than a league per day and in 1449 it took six days to move a cannon from Rennes to Fougères (47 kilometres), a daily rate of 8 kilometres. Yet these statistics compare not so unfavourably with the movement of the traditional siege engines. It took 10 days to take siege engines from London to the siege of Bytham in 1221, an average of 16 kilometres per day. It is unsurprising to find that wherever possible alternative routes were taken for both siege engines and cannon alike; the most efficient means was by river or sea, as during the preparations for the siege of Berwick in 1304.

It is uncertain how effective the early cannon were. At Dortmund in 1388, 27 cm calibre stones were ineffective against its walls, and in 1409 at the castle of Vellexon, the firing of 1,200 projectiles ranging between 700–850 lb also failed to bring down the defences. Moreover, large cannon could not compete with the traditional engines in terms of speed of fire. Five shots per day were released from a single cannon at the siege of Ypres in 1383 and sixteen years later at Tannenburg some large cannon only fired once a day. These rates, however, generally improved over time; moreover, medium calibre weapons could be loaded and fired more quickly. At Tannenburg 6 per day from smaller guns was recorded and at Dortmund 14 per day. By the mid-fifteenth century great advances had been made. In 1428 the English guns at Orléans could release 124 shots over twenty-four hours, and at the siege of Rheinfelden in 1445, these weapons fired at a rate of 74 per day. Standardization, modest calibre, and their greater speed of fire meantthat by the fifteenth century these weapons were now far more efficient than traditional siege engines. Christine de Pisan had already estimated that 262,000 projectiles from traditional engines would be required to overcome the defences of a well-fortified town, but that only 52,170 would be required if firearms were used, a reduction of over 5:1.

The German Feuerwerkbuch in its several versions was widely read throughout Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Derivative of, but distinct from, Konrad Kyeser’s Bellifortis (1405), this page from a Feuerwerkbuch manuscript (1420s) depicts a number of weapons: cannon, handguns, and crossbows firing incendiary bolts. Note the countermeasures being taken by the defenders to remove these devices from the roofs.

Siege was a slow business. It was inevitable that conventions of siege would be established at every stage. These were affected by the rules of the just war and the code of chivalry in just the same way as battle. It was therefore vital to establish when a siege began and when it was concluded. The firing of a shot from a siege engine, later from a cannon, or the throwing of a javelin or spear or pebble, often symbolized the commencement. White flags, the handing over of keys (as at Dinan on the Bayeux Tapestry) and other acts demonstrated that surrender had been offered. By treating with the enemy, a defending captain could reduce the destruction to his town or castle and its population on its surrender. But conditions for surrender too were carefully codified. At Berwick in 1352, Richard Tempest was required to endure three months of siege before negotiations could begin. Often, however, hostilities were suspended, offering the chance of relief from external forces for the besieged. In such instances the rules were strict: for the besiegers, no further siege engines or men could be brought up into position, while the besieged were forbidden to make repairs. The giving of hostages sought to strengthen any such truce. On occasion, the terms were broken and hostages put to death. Even if a relieving army arrived, it was required to come prepared for battle, often at a time and place appointed by the besieger. At Grancey in 1434 it is reported that the armies were to meet ‘above Guiot Rigoigne’s house on the right hand side towards Sentenorges, where there are two trees’. Advantage was with the besiegers with their foreknowledge of the field and the ability to occupy the best position. If no relief came within the time set, then the besieged garrison was obliged to surrender. If unconditional, much was made of this. Those leaving were sometimes forced to come out barefoot, as at Stirling in 1304, or at Calais where in 1347 the six most prominent citizens had to wear halters around their necks when they brought out the keys of the town to Edward III. Negotiation played a large part in the siege. The safety of negotiators, often clerics, was recognized by both sides. If, however, the stronghold was taken by storm, the successful had almost complete control over the defeated, inflicting rape, enslavement, murder, and the seizure of property; terrible massacres followed many successful sieges during the Albigensian Crusade and the Black Prince notoriously sacked Limoges after its recapture in 1370, though the number of civilian victims remains uncertain.

In this chapter the focus has been on the attack and defence of castles, the evolution of their design, and the changing weaponry ranged against them. The emergence of the private defence separates the middle ages from other periods in which the emphasis was placed on public, communal defence, though most major towns and many smaller ones spent heavily on their defences in this period, and successful sieges of towns, especially during the Hundred Years War, constituted some of the most notable military achievements of the age. In the main the evolution of medieval town defences mirrored the advances made in castle design, though borrowings were not all in one direction: masons were sent to view the town gate at Rennes when the castle of Blain was remodelled in the 1430s. Despite improved weaponry, the major tactics of siege—assault, bombardment, mining, and blockade—changed little. Similarities in the siege tactics used against Constantinople by the Russian Prince Oleg in 907 and later, successfully, by the Turks in 1453 bear this out, while the capability of castles such as Château-Gaillard, built in an earlier era, to withstand artillery siege at the end of the middle ages also demonstrates the longevity of castle designs against ever-changing firepower. The period is notable for its underlying continuity of practice in attack and defence. One of the many reasons for this remained a continuous adherence to the advice offered to besiegers and the besieged in Vegetius’ De Re Militari, first copied by the Carolingians. Six chapters of this text are devoted to fortification including where to site a stronghold, how the walls, ditches, and gatehouses should be built, and how to counter fire and eliminate injury to personnel. Four chapters deal with preparations for siege such as building defensive siege engines and provisioning, and a further 18 chapters are concerned with siege strategies for both attack and defence. Vegetius remained the textbook for all military commanders and was studied down to the end of the middle ages.

It is perhaps not surprising, given the predominance of siege during the medieval period, and the scale of the operations which affected all strata of society, that numerous accounts of sieges have come down to us through chronicle and other literary sources. Few other events can have had such a profound effect on national and local psyche and morale; this is perhaps why the siege became the literary metaphor or allegory for the struggle between good and evil in didactic texts, or those reflecting the lovers’ tribulations. It is important, however, not to overestimate the importance of actual sieges. Of the thousands of fortifications constructed across Europe at this period only a minority were besieged. Many survived several hundred years, frequently refurbished and adapted to new circumstances, without their efficacy ever being tested in earnest. For most of the time, castles and town defences were not directly threatened by assault or blockade; though it cannot be tackled here the story of fortifications in peacetime is an equally fascinating history.

Siege of Rhodes, 1480. The vast numbers of men and weapons deployed in late medieval sieges is perfectly demonstrated in this scene. The improvements to town defences can be seen by the double circuit of masonry walls, the regular flanking towers, and the cannon embrasures placed in the advanced line of walls.