18.

AS ATTESTED BY SPECIMENS dating back 400,000 years, whether thrown or employed in thrusting attacks, the spear has generally been one of the first weapons fabricated throughout the world. Despite assuming many forms, ranging from a sharpened, sometimes fire-hardened length of wood to elaborately cast bronze variants mounted on shafts carved from the rarest timbers, the objective was simply body penetration.1 However, the addition of a triangular head with sharpened edges, initially of stone but eventually cast from metal, enhanced the spear’s capabilities by enabling a new attack mode, slashing and cutting.

Although stone spearheads increased the weapon’s lethality, their use entailed multiple problems. Within weight and balance constraints, effective sizes and shapes had to be determined; methods for mounting and fastening developed; and workable minerals sought out, quarried, and prepared. Long, thin spearheads can achieve great penetration but generally cause more limited wounds and, being brittle, are liable to break at every stage from fabrication to impact. Broader blades require greater strength for penetration but make retraction difficult and generally inflict more significant damage. Small heads are light but lack impact; larger, heavier ones transfer greater energy but can shift the center of gravity too far forward, making them cumbersome to use and difficult to control when thrown.

In ancient times the combined length of the shaft and blade could vary greatly, but essentially depended on whether the warriors fought as individuals on a relatively dispersed battlefield or in closely packed, disciplined formations. The maximum length that can be effectively wielded by one hand in combination with a shield in the other has historically averaged about two meters or seven feet. Any longer and the weight of the shaft, coupled with the disproportionate effect of the head at the end, causes the spear to become unmanageable except for the very strongest warriors or through rigorous training. (Contemporary martial arts practice shows that skill sets can be learned that will enable a fighter to single-handedly employ a three-meter spear, but generally only in a very dynamic mode, featuring excessively large swings and considerable body involvement that create indefensible openings for enemy strikes and threaten nearby comrades.)

Because longer shafts generally require two hands to wield and make it impossible to employ a shield, fighters are compelled to depend on agility, body armor, and cooperative action. However, spears also increase the thrusting range, provide a significant advantage against enemies armed with short weapons such as a sword or axe, and make it possible to target chariot and cavalry riders and their horses. Nevertheless, depictions from Mesopotamia, Greece, Egypt, and even Warring States China show that long spears were used single-handedly in a downwardthrusting mode by mounted chariot fighters, contrary to claims that the spear’s obsolescence in China resulted from its inherent uselessness in chariot warfare.2

Traditional Chinese lore sometimes credits Shao-k’ang’s son Chu with inventing the spear, a rather unlikely possibility given the spear’s preexistence at the time, but possibly indicative of him having been the first warrior to bind a bronze spearhead to a wooden shaft. Archaeological evidence shows that in China the earliest stone spearheads were mounted by inserting them into a slot at the top of the shaft, then securing them, however precariously, with lashings and bindings. Irregularity in early shapes and the slipperiness of certain minerals that required roughing and grooving must have enormously complicated the task of solidly affixing the head to the shaft. The advent of bronze casting mitigated the problem because metallic spearheads could be molded with an internal cavity or socket extending well into the spearhead. Preshaped, tapered wooden shafts could then be inserted a considerable length, resulting in a tight fit and minimal tendency to rotation when oval and rhomboidal shapes were employed. Other than the p’i, all known Shang bronze spears use this method of attachment, a practice that continued right through the Warring States period.3The spear’s balance was improved by adding a blunt cap at the bottom of the shaft (in contrast with the pointed ones used for dagger-axes).4

Unlike the ko, whose shaft might snap at weak points along its length from sudden perpendicular (shearing) forces, the spear’s vulnerability lay in buckling under compression when the spearhead struck and was thrust into an object. As evident from the K’ao-kung Chi’s emphasis on the need for a circular cross-section and no reduction in thickness even at the handhold, consistent thickness and strength were therefore required along the entire length. Unfortunately, apart from one specimen recovered from Ta-ssu-k’ung-ts’un in the Anyang area with an original shaft length of 140 centimeters, nothing more than short remnants and impressions in the sand remain from the Shang. However, a 162-centimeter Warring States shaft constructed from long bamboo strips that had been laminated onto a wooden core and then lacquered black shows that the problem was thoroughly comprehended and illustrates the engineering sophistication eventually achieved.5

Even though the stone precursors that have been found in Yangshao and Ta-wen-k’ou sites attest to the spear’s employment in the late Neolithic, it is only with the inception of bronze versions that it would assume a focal role. No bronze spearheads attributable to the late Hsia or Erh-li-t’ou, Yen-shih, Cheng-chou, or even Fu Hao’s tomb have yet been discovered, and the spear appears to have remained relatively uncommon prior to the late Shang, despite requiring relatively little bronze in comparison with the solidity of axe and dagger-axe blades. In fact, the earliest Shang bronze spearheads appear in peripheral southern culture and the Northern complex, reputedly the twin sources for the modified Shang style that would rapidly proliferate late in their rule from Anyang.6

Since few spearheads have been recovered even from Yin-hsü’s early years, the spear’s history falls into the latter half of the Shang rule from Anyang, when their numbers seem to have rapidly increased.7 As might be expected given that older bronze spearheads retained an intrinsic value even as newer forms evolved, several styles are visible in the artifacts from Yin-hsü. In addition, just as with the ko and yüeh, nonfunctional ritual forms that complicate the assessment of combat designs have also been recovered. Distinguished by the thinness of their blades and the absence of sharpening, they gradually became longer and more elaborate, even occasionally assuming oversized forms similar to the long stone spear found at Liaoning, which dates to the dynasty’s end.8

The spear actually appears under a number of different names, some simply regional identifications, others derived from a distinctive aspect, such as the p’i.9 However, whether longer or shorter, blunter or smoother, decorated or not, without exception Shang era spears always have just two leaflike blades, presumably in imitation of stone precursors.10 Even variants with pronounced rhomboidal spines that could have functioned as additional blades with minimal enlargement and sharpening were never transformed into four-edged spearheads, nor did three-bladed models emerge.

Shang era bronze spears have now been divided into three main categories: the southern style, northern style, and a composite embodiment whose derivation remains controversial.11 Although few dedicated studies have been published, based on numerous recovered specimens it has generally been concluded that what might be termed the southern style was the main source for the Shang bronze spear.12 Apart from a single, rather primitive-looking specimen recovered out at T’ai-hsi, the very first bronze spears are in fact the three found at two sites at P’anlung-ch’eng at the Shang’s southern extremity, one of which is shown overleaf.13

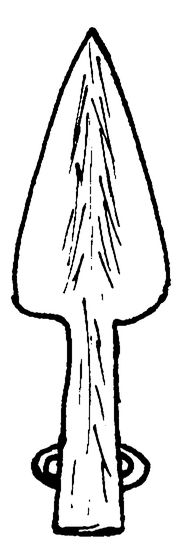

All three have long willowy blades with raised spines, gradually expanding mountings, and a raised rim at the base. Two of the three are further distinguished by the opposing earlike protrusions low on the base, which functioned as lashing holes for securing the head to the shaft rather than for attaching pennants or decorations, as in later periods.14 Furthermore, two have slightly oval openings, while the third is somewhat rhomboidal.15

Although the presence of “ears” has been energetically asserted to be the defining feature for southern tradition spears, sufficient exceptions ranging from single examples to small groups have been recovered in Hubei, including at Hsin-kan, to constitute another type.16 Proponents of the southern tradition tend to dismiss their importance by noting that they all date to the Yin-hsü’s second period or later, thereby implying (without ever specifying) that they are synthetic types that meld Shang influences (which is somewhat problematic given the lack of Shang precursors) with indigenous characteristics. At Hsin-kan, where the spears outnumber the ko thirty-five to twenty-eight, twenty-seven of the former do not have the distinctive ears required of the southern type, and another was found at Wu-ch’eng that reportedly exerted a formative influence on Hsin-kan.17However, the twenty spears recovered at Ch’eng-ku in Shaanxi (previously mentioned in connection with the southern yüeh tradition) all have ears in addition to somewhat pudgy, leaf-shaped blades and decorated bases and are said to be somewhat larger than those at Hsin-kan in comparable styles.18

The so-called northern style that appeared about the same time not only lacks “ears” but instead employs wooden pegs inserted into holes in the base to secure the spearhead onto a round shaft, thereby sufficiently augmenting the basically secure mechanical fit to prevent rotation and the head’s loss in combat. Generally more elongated than southern-style spears, they are also simpler in appearance and normally lack decoration. Their similarity to spearheads recovered from the Shintashta-Petrova and Andronovo cultures suggests an external origin for this style, but no studies have yet assessed the possibility.

The Shang bronze spears recovered at Yin-hsü are said to be primarily based on the southern style or to integrate both northern and southern features in conjoining some form of ears intended for lashing with a heavier rim, pegging holes, and a rhomboidal socket.19 However, if pegging and a circular (rather than oval) receptacle are considered definitive northern contributions, enough exceptions have again been discovered to seriously undermine any claim to a true Shang synthesis, even though pegging would increasingly become the preferred method from the Western Chou onward.20

Despite sometimes extreme variations in shape, length, and decoration, late Shang spears assume two primary forms. The more common one, somewhat simplistically identified as the “Shang spear,” has a rather dynamic, unbroken contour as its elongated leaf-shaped blade continuously extends down to the rim in a sort of wavelike pattern that first bulges out, then curves inward before finally expanding once again toward the bottom, where lashing holes are usually incorporated. In some variants the blade extends all the way down; in others it cuts inward, leaving a short length of clearly defined shaft that may or may not have a rim.21

The other primary form that suddenly appeared in the second period and is also, if confusingly, sometimes identified as the definitive Shang spear, consists of a sort of pudgy-looking, adumbrated, leaf-shaped blade, an obviously protruding spine, short lower shaft, and two ears, as shown overleaf.22 Thereafter, most Shang spears would be marked by ears in one form or another, though more “earless” versions have been recovered than is generally credited. Both styles initially flourished in the Western Chou, but a shift over the centuries saw a continuous reduction in the blade’s waviness, resulting in the longer, thinner, more dynamically contoured and lethal shape that predominated in the Warring States period.

The spear’s battlefield role and relative importance in the Shang have long been debated. The number of bronze spearheads recovered from individual Anyang era graves, tombs containing sets of weapons, or collections of internments in a confined area, although cumulatively second only to the dagger-axe, is usually far lower than the latter. It has even been asserted that the simple character for spear (mao) doesn’t appear in the oracular inscriptions, though there are dissenting views.23 However, the spears recovered from Yin-hsü are almost invariably found in weapon sets rather than in isolation, including with yüeh.24 It was nevertheless held that though officers carried yüeh, the dagger-axe was the era’s primary combat weapon, and spears played an uncertain but supplementary role. However, relatively recent discoveries have cast considerable doubt on this interpretation, one being the grave of a presumably high official with considerable martial authority discovered in the Anyang area itself that contained 730 spearheads but only 31 ko.25

The grave at Hou-chia-chuang consists of several layers that contain a variety of ritual vessels and weapons indicative of high rank and military power, and the weapons are arrayed in a way that suggests they once furnished the arms for a military contingent. (This hoard would seem to at least partially confirm the claim that weapons were monopolized by the government, manufactured and stored by Shang authorities, and only dispersed for military activities.) The spearheads were found clumped together in bundles of ten but distributed into two layers consisting of 370 in the upper and 360 below. However, the import and significance of this arrangement remain undetermined. Were the weapons intended for a unit of 360, the second layer being replacements for the first 360, whether fully made up with shafts or simply maintained as spare spearheads to allow battlefield fabrication or replacement as necessary? Or were they intended for a second company of 360, in which case the total operational unit would closely approximate a modern army battalion?

The low number of dagger-axes at Hou-chia-chuang has prompted claims that the spear had already become the army’s primary weapon in the late Shang, in which case commanders for squads of ten were wielding ko and higher-ranking officers carrying yüeh. However, other explanations are possible, including that spears represent a new form of weaponry and were therefore held in central storage, whereas dagger-axes were more widespread, essentially individual possessions. Conversely, the spear is an effective battlefield weapon whose length and mode of action would have easily outranged the era’s ko, could have been usefully employed against the increasing numbers of horses, and certainly required less combat space in a thrusting mode, making it more suitable for a packed battlefield than a dagger-axe employed in overhand or sidearm strikes.

Minor confirmation that spears were becoming important shortly after Wu Ting’s reign appears in the tomb of Commander Ya—who has already been mentioned in connection with the seven unusual yüeh that accompanied him into the afterlife—in which slightly more spears (76) than dagger-axes (71) were recovered.26 Furthermore, the 30 ko and 38 spears found among the weapons interred with a high-ranking Ma-wei nobleman dwelling in Anyang in Yin-hsü’s fourth period augment the evidence leading to the conclusion that the spear had begun to assume a battlefield role and that the nature of combat was in transition.27

Finally, whatever their relative proportions in the Shang, there is no evidence that spears were ever employed as missile weapons in the manner of ancient Greek javelins. This may have been a consequence of the high value placed on bronze, the inconvenience of warriors each having to carry several cumbersome javelins or similar spearlike weapons, or simply the inappropriately short length of slightly less than 150 centimeters. Nor, despite the long tradition of traditional martial arts slashing techniques and the spear’s highly esteemed role in the Wushu world, can it be concluded that spears were ever employed other than in a piercing mode.

Fairly detailed knowledge of the lamellar armor developed in the Warring States period has been acquired as the result of excavations conducted over recent decades, but even impressions of Shang armor and shields have generally proven elusive because of the rapid degradation of nonmetallic materials. However, this lack of artifacts has not prevented highly speculative discussions and several imaginative attempts at reconstructing armor’s inception. Nevertheless, by focusing on the few known impressions and artifacts, some sense of Shang, though not Hsia, armor can be gleaned.28

Designs varied imaginatively over the centuries, but priority was always given to the head, then the chest, shoulders, and finally the waist downward. Because percussive blows could be—or more correctly, had to be—simply blocked or warded off, defensive coverings were basically expected to provide protection against arrows and piercing and slashing attacks undertaken with edged weapons. At what stage Chinese fighters began imitating animals and turtles and employed animal skins, furs, or multiple layers of heavy cloth for primitive protection remains unknown, but based on vestiges at Anyang, it certainly predates the Shang.

Perhaps because they lack the gleaming appeal of burnished bronze or the thrill of martial power, shields and armor have rarely been associated with the legendary Sage progenitors of antiquity. (The Spring and Autumn anecdote of penetrating seven layers of armor well illustrates the normal propensity to lionize the bow and arrow while deprecating the role of armor.) However, Shao-k’ang’s son Chu, who eventually restored the clan’s power amid the internal chaos that beset the early dynastic Hsia, reputedly fabricated the first body armor in order to survive the Yu-ch’iung’s deadly arrows.

As attested by vestiges of large leather panels at Anyang, the earliest Shang body armor was apparently a two-piece leather tunic that should have provided some protection against glancing attacks, even though ancient skeletons show that arrows and piercing weapons could penetrate and circumvent it.29 Decorated with abstract t’ao-t’ieh designs in red, yellow, white, and black,30 Shang armor seems also to have been sometimes partially adorned, rather than layered, with very small bronze pieces. However, although it appears that additional pieces of leather may have eventually been employed for the shoulders, no major improvements can be proven until the early Chou, when more flexible corsets began to be fabricated by employing lamellar construction techniques that linked small leather panels together with hempen cord. Thereafter, it was merely a question of time before metal plates would be substituted, eventually resulting in much of the well-known body armor visible on Ch’in dynasty tomb figures.

Although no examples have yet been recovered, shields constructed from interlaced soft wooden materials, leather, or even leather thongs certainly predate the Shang and would continue to be employed for the next three millennia by peasant forces and in isolated localities. Shang variants were apparently produced in two sizes, a moderate version for infantry warriors confined to the ground and a larger version that is still unattested apart from depictions of shields for chariot fighters intended to block incoming arrows and strikes down the full length of the body and perhaps even cover a compatriot fighting alongside. Materials employed to fabricate these shields seem to have again included thin wooden slats, interlaced bamboo or other reedlike materials, and leather, as well as a leather covering on an underlayer or two of fibrous matter, all stretched and affixed to a simple frame consisting of roughly three-centimeter wooden poles.

From depictions preserved in oracular characters and a body buried with a dagger-axe and shield, it is clear that the moderate-sized, single-handed shield was held in the left hand and used in conjunction with a dagger-axe or short spear in the right. Impressions made by a cache of shields somewhat chaotically deposited in tomb M1003 and a famous reconstruction based on vestiges in tomb M1004 indicate that they were slightly rectangular and had rough dimensions of 70 by 80 centimeters (27.5 by 31.5 inches), or about half a man’s height and thus slightly shorter than the era’s dagger-axes and single-handed spears.31 They were held by a vertical handle in the center and had a slight outward bow that should have improved the dynamics of blow deflection while facilitating the warrior’s grasp.

Traces in the compacted soil further indicate that leather versions were also sometimes decorated with t’ao-t’ieh patterns similarly painted in vivid red, yellow, white, and black and even tigers or dragons, as described and found in later times.32 The nobility and high-ranking officials apparently affixed small supplemental bronze plates that would certainly, if spottily, have increased the shield’s penetration resistance even though they were probably intended mainly as decorative embellishments. One bizarre variant of the infantryman’s shield called a ko-tun (“dagger shield”) even mounted a dagger-axe blade perpendicularly at the top, but its possible utility except as a sort of jabbing distraction in the enemy’s visual field is difficult to imagine.33

Helmets, presumably of interlaced rattan but possibly leather, also appeared in the Neolithic, and a somewhat lesser-known legendary account appropriately attributes their invention to Ch’ih Yu, even though his aggressive behavior should have prompted others to create them as a defensive measure against his innovative weapons. Whatever form these ancient variants might have taken, no evidence has survived, and the first known metallic helmets appear in the Shang. However, they remain surprisingly sparse in comparison with the vast numbers of weapons that have been recovered and Shang willingness to employ bronze for large ritual vessels, with only one large aggregation having been discovered and a few deposited in the weapons hoards found in scattered high-ranking tombs.34

Although several variants can be distinguished, Shang helmets were basically designed to protect the skull from the forehead upward but also extended downward sufficiently to normally, but not invariably, encompass the ears and the back of the neck. Given that some large yüeh and shield decorations were molded with bulging eyeholes, they surprisingly did not provide any integrated means of facial defense, a deficiency that may have been remedied with a bronze face mask in exceptional cases.35 Cast from bronze as a single unit that weighed from 2 to 3 kilograms (a weighty 4.5 to 6.5 pounds) and averaging some 22 or 23 centimeters in height, they were apparently worn with an inner head wrap or intermediate padding that was designed to cushion the effects of blows and protect the skull against wounds that would invariably have been caused by the interior’s roughness. In contrast, the exteriors are all smooth, polished, symmetrical executions of somewhat startling designs that feature stylized projections and protuberances that not only augment a warrior’s frightening visage but also strengthen the helmet’s structure and increase the distance between the skull and the strike.