Unexpectedly, on August 4 1942 just as Generalleutnant Scheller took over the 9th Division command post, the unit was withdrawn from the front lines. Passing through Shchigry, Fatezh and Orel, it reached the operational region of the Army Group “Mitte” north of Orel. On August 11, the Division reached Bolkhov, where it was incorporated into the XXXXI Armoured Corps (XXXXI PzK) of the 2nd Panzer Army under General Schmidt. In the middle of August, the Germans launched an attack on Kaluga from the region north of Bolkhov. Their advance towards Sukhinichi, was meant to counteract the Russian offensive headed for Rzhev.1 The intent of the operation, code named “Wirbelwind” (“Whirlwind”), was to break through the defences of the Soviet 16th and 61st Armies, and conduct an assault in the direction of Sukhinichi. The next stage of the operation was to position the forces in the region west of Yukhnov. Such a move would threaten an entire left flank of the Soviet Western Front. A total of eleven divisions, including the 9th and the 11th Panzer Divisions and the 25th Motorised Infantry Division participated in the operation. The units listed above had some 400 combat vehicles. The Luftwaffe was to provide an extensive air support throughout the operation. As mentioned before, Generalleutnant Walter Scheller was at the time the commanding officer of the 9th Panzer Division, the 33rd Panzer Regiment was led by Oberst Wilhelm Hochbaum, while the 9th Armoured Grenadier Brigade was commanded by Oberst Heinrich-Herman von Hülsen. The 10th and the 11th Armoured Grenadier Regiments were under command of Oberst Willibald Borowietz and Oberstleutnant Joachim Gutmann respectively. Oberst Walter Gorn was in charge of the 59th Motorcycle Rifles Battalion at the time.

An August 11 the units of the 2nd Panzer Army conducted a surprise attack at the junction of the sectors occupied by Soviet 16th and 61st Armies. The German units swiftly overcame the defences and drove a narrow wedge some 35 to 40 kilometres deep. The attackers reached the Zhizdra River near Usty and Belyy Kamen.

The report dated August 12 indicates that the 33rd Panzer Regiment had 110 tanks.

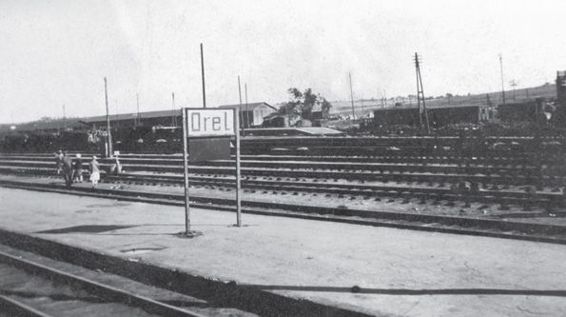

Town of Bolkhov; the 9th Panzer Division passed through the area on August 11, on the way to join the 2nd Panzer Army.

On the same day Generaloberst Halder noted in his journal: “The Army Group “Mitte” is experiencing its first difficulties, the way for the 11th and 9th Panzer Divisions has to be fought for.”2 The 9th Panzer Division was proceeding on the right wing of the 2nd Panzer Army right behind the 11th Division. As a result of the German advance, three rifle divisions of General Bielov were cut off from the main forces. At the same time, another grouping of German units attacked the 322nd Rifle Division positioned on the left wing of General Ivan Bagramian’s 16th Army, defending the Rossieta River perimeter. With that series of moves, the Germans hoped to reach the Zhizdra River and join their main assault forces fighting against General Bielov’s units. Despite the fact that General Bagramian deployed his reserves, the Germans managed to reach Zhizdra between Gretnia and Usty. The 322nd Rifle Division sustained very heavy losses, nonetheless it avoided being sacked and withdrew to the other side of the river. As the German objectives and the magnitude of the operation became evident to the Soviet command, General Bagramian issued two orders:

the 10th Tank Corps under General Burkov was to move out of Sukhinichi region and by morning of August 12 position its forces at the north bank of Zhizdra behind the left wing of the army. The Corps was to prepare for a southward counterattack against the German units, which broke through the defences of the 61st Army.

the defence perimeter of the 5th Guard Rifle Corps led by Major General G. P. Korotkov, was to be taken over by the neighbouring units and the 31st Guard Rifle Division deployed from the army reserves. Meanwhile General Korotkov’s Corps was to march through the night to be able to concentrate its forces near Aleshinka on the north bank of Zhizdra by the morning of August 12.

In an additional move, the Soviet 1st Guard Cavalry Corps was positioned behind the left wing of the Soviet armies. On August 14, Generaloberst Halder recorded that: “The “Wirbelwind” attack is progressing, but a strong and determined defence, as well as fortified terrain allow for only a slow advance.”3 Usty township was eventually taken by the 10th Armoured Grenadier Regiment. The entry in the “Combat Journal of the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces” (KTB des OKW) dated August 16 states: “Operation “Wirbelwind” conducted by the Army Group “Mitte” achieved very little with exceptionally heavy losses. Generalfeldmarschall von Kluge, reports via telephone that the attack cannot penetrate the enemy lines through the forests near Sukhinichi, because there is one stronghold after another, and the passages between the woodlands are protected by mine fields. ”4

Staff consultation with Generalmajor Walter Scheller, commander of the 9th Panzer Division, before operation “Wirbelwind”.

A frontal command post in the forest near Shizdra, during operation “Wirbel-wind ”. Generalmajor Scheller is seen near the command version of the halftrack armoured transporters Sd.Kfz. 251/3.

On August 17, the 9th Panzer Division along with the 439th Infantry Regiment (Inf.Rgt. 439) from the 134th Infantry Division (134. Inf.Div.) fought in the area of Svetlyi Verch and Tscherebet. The units were able to make contact with the 446th Infantry Regiment (Inf.Rgt. 446) of the same 134th Infantry Division, so the encirclement of the Soviet units defending the area, so called “little pocket” could be completed.5 The same day of August 17, Oberstleutnant Gorn, commander of the 59th Motorcycle Rifles Battalion received the Knight’s Iron Cross with Oak Leaves as the 113 Wehrmacht trooper awarded this decoration. The little pocket was cleared of enemy troops by August 18 1942.

As a coincidence, that day, the 394 day of the Russian Campaign, marks the destruction of the 1000th Soviet tank by the 9th Panzer Division. By that time, the Division reached the intended bridgehead at Gretina. As the Germans arrived at Zhizdra River, for a few days they attempted the crossing in order to press towards Sukhinichi. With extensive support of the tanks, but suffering heavy losses, the river was finally crossed near Glinnaia, allowing a narrow entry point into the forests south of Aleshinka. At that juncture, the German motorised infantry came under a massive heavy artillery barrage from the Soviet artillery brigade. In the meantime, the counter-attacks conducted by 146th Tank Brigade and the units of the 11th Guard Rifle Division pushed the German forces back into the woods. Soviet accounts claim that the enemy units were obliterated by Major General A. W. Kurkin’s 9th Tank Corps, but this statement is over exaggerated. Nevertheless, the German advance came to a standstill. The 11th Panzer Grenadier Regiment was involved in a fierce fighting near the township of Bogdanovo - Kolodezi. The casualties were so intense that in some companies the number of soldiers was reduced from the full strength to only about 10 or 15. Meanwhile, other German units attempted to move northwest from the Gretnia region towards Sukhinichi, but concentrated artillery fire and the Soviet counterattack forced them back to their starting positions. The battle was at its culmination. The Soviet 16th Army managed to hold its ground, forcing the enemy into the defensive. The determined resistance and the counter-attacks conducted by the rifle units supported by the 3rd, 9th and 10th Tank Corps’ brought the German attack to a halt. Thus, after the initial accomplishments of Wehrmacht between August 11 and 15, the units were stuck in the forests on the north bank of Zhizdra River. German sources state that the particularly bloody battles were fought between August 20 and 25. Some interesting information about the affairs on August 20 1942 may be found in a letter from Oberstleutnant Gustav-Adolf Bruns, commander of the 74th Panzer Grenadier Regiment (Pz.Gr.Rgt. 74) to the town mayor of Hamlen, “Brief des Kommandanten an den Oberbürgmeister der Stadt Hameln”. The letter contained a report on the breakthrough assault conducted by the 74th Panzer Grenadiers against the Soviet positions in the forest northeast of Gretnia, “Gefechtsbericht über den Durchbruch des verstärkten Panzer-Grenadier-Regiment 74 durch den Wald nordöstlich Gretnja am 20.08.1942”.6 According to this account, the reinforced 74th Panzer Grenadier Regiment was temporarily assigned to the 17th Panzer Division on August 19. The assignment resulted in a transfer from Kolmkschtschi vicinity to the area east of Gretnia. The regiment was ordered to breach the Soviet defences and join forces with the 63rd Panzer Grenadier Regiment (Pz.Gr.Rgt. 63) under Oberstleutnant Hermann Seitz. At the time, this unit was operating as the “Seitz” Combat Group (“Gruppe Seitz”); it had reached the southern outskirts of Aleshinka village but was cut off from the rest of the forces. According to the plan, the 74th Panzer Grenadier Regiment was to aid the Group in capturing Aleshinka. The regimental command was also aware that south of “Seitz ” Group there is another German unit positioned in a nearby forest clearing. It was the III Battalion of the 15th Panzer Regiment (III/Pz.Rgt. 15) commanded by Oberst Hochbaum7, which was not able reach the “Seitz” Group due to strong enemy resistance. During the night of August 19 and 20, the Battalion, referred to as “Hochbaum” Group (“Gruppe Hochbaum”), assumed an all-round, deep defensive formation. On August 20 at 3:30 in the afternoon, the 74th Pz.Gr. Regiment entered the woods. At first, the march was uninterrupted, but before reaching the “Hochbaum” Group’s positions, the I Battalion of the 74th Regiment (I./Pz.Gren.Rgt. 74) was drawn into a series of forest skirmishes with Soviet units. After some fierce fighting, the Soviet troops were pushed away from the path of the Regiment. At about 4:55 in the afternoon a link with the “Hochbaum” Group was established. During the subsequent fighting, the 74th Regiment was able to clear the area northwest of the “Hochbaum” Group’s stronghold, pushing back the Soviet units. However, the advance aimed at joining the “Seitz” Group, which was conducted along the road, failed even though all the reserves were utilized. The frontal attack undertaken afterwards, was also ineffective in the heavily wooded area. On top of that, two German tanks moving down the road were destroyed by a Soviet anti-tank gun firing from a concealed position. The losses had an effect on morale, causing an understandable caution of Oberst Hochbaum’s armoured unit. The attack subsided “under a horrid infantry, mortar, anti-tank gun and artillery fire, while the casualties accumulated.”8 To reinforce the struggling units, Generalleutnant Scheller of the 9th Panzer Division dispatched the 17th Motorcycle Rifle Battalion (Kradsch.Btl. 17), the 59th Motorcycle Rifle Battalion, the II Battalion of the 11th Panzer Grenadier Regiment and the remains of the III Battalion of the 446th Infantry Regiment (III./Inf.Rgt. 446). The above units became the Combat Group “Burns” (“Kampfgruppe Bruns”), and were assigned to the 74th Panzer Grenadier Regiment. The unit closest to the surrounded “Seitz” Group was the II Battalion of the 11th Panzer Grenadier Regiment. The battalion received an order via radio to move north towards the concentration point of the Combat Group “Burns”. However, the unit encountered such a strong enemy opposition that it could not proceed. The 17th Motorcycle Rifle Battalion and the 59th Motorcycle Rifle Battalion, led by Hauptmann Tescher and Oberstleutnant Gorn respectively, were deployed in accordance with the earlier reconnaissance conducted to the right of the 74th Panzer Grenadier Regiment. Their objective was to slip by the unguarded flank of the enemy, while the I Battalion of the 74th Panzer Grenadier Regiment conducted a frontal attack, in order to secure a supply corridor leading to the “Seitz” Group. As the above aim was achieved, the motorcycle units joined by the II Battalion from the 74th Panzer Grenadier Regiment were to continue in the effort to encircle the enemy. In front of the attackers, there lay three sectors of enemy defences hidden in the forest. The letter mentioned above, contains a description of the fighting: “the determined enemy had to be challenged for each square meter of ground, the opponents used medium artillery barrages and constant mortar fire to repel our troops.”9 At around 15:00 hours the Germans managed to break the defences, and one hour later “… a surrounded “Seitz Group” could be greeted with a hand shake.”10 As it turned out, the forest was defended by the reinforced regiment from the 326th Rifle Division.11

A sign commemorating the 1000th tank destroyed by the 9thPanzer Division on August 18 1942. The photograph was taken by Kriegsberichter (war reporter) Kraayvänger from Pz.P.K. 693 ( Panzer Propagandakompanie ). It was later distributed in a form of a postcard for propaganda purposes.

“The enemy regiment was, according to its commander who was taken prisoner, completely wiped out. The prisoners were only sporadically taken. The battlefield showed the wrath of nearly 10 hour long intense fighting.”12 By the evening hours, most of the forest west of the road was secured, including the crucial sector where the enemy received reinforcements coming from the village of Bogdanovo - Kolodezi. The village was captured by the Germans around noon, but was recaptured by Red Army units soon after.

On August 20, the 33rd Panzer Regiment had 94 operational tanks.

As the battle evolved, the German headquarters made new decisions. On August 22 during a conference between the Führer and Generalfeldmarschall von Kluge it was decided that: “The “Wirbelwind” operation will be aborted because the terrain difficulties and the presence of strong enemy forces does not allow for achievement of any notable success. However, the enemy units in the area should still be tied by spurious attacks so they could not be used at the other, weaker sectors of the front. To execute this order the 2nd Panzer Army will not obtain any reinforcements; in fact, the 9th and the 11th Panzer Divisions should be withdrawn and transferred to the region north of Kirov. From that point, they should, in cooperation with the “Grossdeutschland” Motorised Infantry Division ( Infanterie-Division “Grossdeutschland” (mot)), operate in the general direction of southwest, trying to achieve a “little solution” to the “Wirbelwind” Operation.”13 During the next few days, the departure of the 9th and the 11th Panzer Divisions was reconsidered. The dialogue between the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht and the Army Group “Centre” continued, with the latter opting in favour of the withdrawal. Meanwhile, on August 22, the units of the Soviet Western Front launched an offensive towards Kozelsk. On August 24 Fahnenjunker Ludwig Bauer in a Pz.Kpfw. III tank armed with long barrel KwK 39 L/60 50 mm gun, survived another hit from a 152 mm artillery shell. Leutnant Rocholl, a crew member named Grosshammer, and the driver were seriously wounded in the incident.14

On August 25, the “Wirbelwind” Operation was completely abandoned. The entry in the “Kriegstagebuch” of OKW states: “The overall situation unchanged. At Sukhinichi, as previously decided, the withdrawal of the 9th and the 11th Panzer Divisions from the 2nd Panzer Army should be conducted. But the question if they should be deployed north of Kirov remains open.” By August 25, the German units pulled back behind the Zhizdra River where a new defence line was constructed. According to Soviet sources, the Germans lost some 10,000 soldiers and over 200 tanks during operation “Wirbelwind”.15 The 33rd Panzer Regiment had 95 tanks on August 31. The total losses included four Pz.Kpfw. II, nine Pz.Kpfw. III (short barrel), 21 Pz.Kpfw. III (long barrel), five Pz.Kpfw. IV (short barrel) and five Pz.Kpfw. IV (long barrel) tanks, 44 vehicles in all. In the meantime, the 9th Division received four Pz.Kpfw. III (short barrel) and five Pz.Kpfw. IV (short barrel) replacement tanks.

Army Group “Mitte”: “During a conference held at noon it was decided, in accordance with the Führer’s wish often repeated during his briefings, that the 9th and the 11th Panzer Divisions, south of Sukhinichi, will be withdrawn, and the 95th Infantry Division stationed northwest of Voronezh will be incorporated into the 9th Army.”16 - mentions an entry made on September 1 in the “Kriegstagebuch” of OKW.

The details of von Kluge’s discussion with Hitler are revealed by Generaloberst Halder: “In a few days withdraw the 9th Panzer Division; then the 11th Panzer Division, but only if the winter defensive perimeter will be pushed back 2 to 3 kilometres into the hills. The Führer agrees on the condition that the forest areas will be adequately prepared.”17 Furthermore Halder states: “The Führer wishes to resolve the Kirov situation with the aid of the 9th and the 11th Panzer Divisions.”18

Indeed, on September 1 the 9th Division was pulled out of action at Sukhinichi. The fighting had weakened its units considerably. For example, on September 3 it was reported that the 59th Motorcycle Rifles Battalion had a strength of only 55 troopers.

As mentioned above, the Russians began another offensive in the area of Kozelsk. The fiercest fighting took place in the area of the main assault directed at Ozhigovo. As the rifle units of the 61st Army were not able to reinforce the 264th Rifle Division before the operation commenced, only a single regiment participated in the attack. Obviously, it could not break the enemy defences, cross the river, capture Ozhigovo and prepare the ground for the 15th Tank Corps breakthrough. Thus, the Russian Corps commander decided at midday to dispatch the 17th Motorised Rifle Brigade supported by two motorised fusilier battalions. After a brief artillery bombardment the river was crossed and Ozygovo taken before the end of the day.

On September 3, the 195th Tank Brigade advanced to the opposing bank of the Vytiebiet River and moved towards Perestryazh. The attempt to capture the township straight from the road march formation failed. The Soviet forces encountered a gorge protected by German anti-tank artillery. Soon thereafter, German tanks emerged from the left flank. Despite success in driving back the German tank attack, the Soviet units were temporarily stopped. The Soviet 3rd Tank Army and the assault group of the 16th Army deployed from the north did not achieve any considerable success in their westward attack either. In the evening of that day, the 3rd Tank Corps was almost depleted of its tanks, so it had to be put in reserve of the Stavka - Soviet Army High Command. Hence, on September 4 when the main forces of the 254th Rifle Division reached Ozhigovo, the 113th Tank Brigade under Colonel A. S. Swiridov and the 17th Motorised Rifle Brigade from the 15th Tank Corps had to regroup and transfer to Volosovo, where they joined the 342nd Rifle Division in an assault at Trostianka.

An entry in the “Kriegstagebuch” of OKW dated September 4 cites: “The command of Army Group “Mitte” plans to use the withdrawn 9th and 11th Panzer Divisions not north of Kirov as previously intended, but due to better efficiency of railroad transport and the unloading options, transfer both divisions to the 4th Army region.”19 In the interim, the 9th Panzer Division was directed to assist in counteracting the Soviet offensive. From September 4, the Red Army forces continued with their attacks, but a resolute German defence as well as lack of fresh troops, supplies and ammunition prevented any Soviet breakthrough. It may be argued that during that time Soviet units, rather than advancing, fended off German counter-attacks conducted by the 9th and the 17th Panzer Divisions.

On September 9 amidst the fighting northwest of Belev, the 9th Division was pulled out of action and ordered to a new destination at Gzatsk, to be reached by a road march through Roslavl, Smolensk and Viazma.20 The Germans could afford such a move since the strength of the attacking Soviet units was so depleted that beginning on September 10 the Red Army found itself on the defensive, with the 3rd Tank Army almost entirely withdrawn except for the 1st Motorised Rifle Division and some support units assigned to Generals Bielov and Bagramian. In all, after a loss of nearly 60,000 dead and wounded and nearly all the tanks, the Soviet troops gained only 8 to 10 kilometres of ground.21 The number of tanks available for action in the 33rd Panzer Regiment amounted to 74 on this particular day.

In the Gzatsk region, the 9th Division had a chance to rest, recuperate and resupply after an eight week long combat action. On September 18, Oberstleutnant Gutmann, commander of the 11th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, received the Ritterkreuz as the seventeenth trooper of the Division awarded this decoration.22 By September 20, the number of operational tanks in the 9th Panzer Division rose to 93.

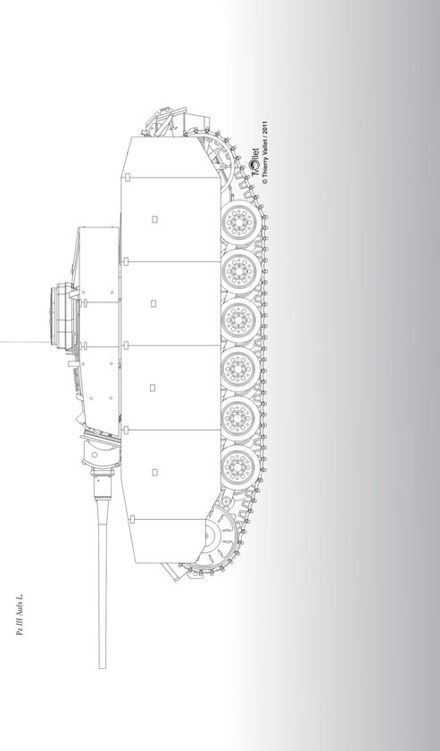

A Pz.Kpfw. III Ausf. L. A fuel drum is carried on the rear armour panel.

1 Bieszanow W, Poligon... op. cit., p. 268-269.

2 Halder F., op. cit., v. III, p. 608.

3 Halder F., op. cit., v. III, p. 609.

4 Greiner H., Za kulisami OKW, Warszawa 1959 , p. 359.

5 http://www.lexikon-der-Wehrmacht.de/Gliderungen/Infanterieregimenter/IR446-Rhtm

6 http://www.hamelner-geschichte.de/index.php?id=52.

7 Quoted as in original. However, the Pz.Rgt. 15 was a unit of the 11th Panzer Division Most likely it was the Pz.Rgt. 33, led by Oberst Wilhelm Hochbaum at that time.

8 http://www.hamelner-geschichte.de/index.php?id=52.

9 Ibidem.

10 Ibidem.

11 The 326 Rifle Division consisted of 1097, 1099 and 1101 Rifle Regiments.

12 http://www.hamelner-geschichte.de/index.php?id=52

13 Greiner H., op. cit, p. 361.

14 http://www.strengerhistocia.com/History/WarArchive/Ritterkreuztraeger/Bauer.htm, http://wwwritterkreuz-traeger-1939-45.de/Infanterie/B/Bauer-Ludwig.htm - both sources contain inaccuracies as to the calibre of the guns. The KwK 39 L/60 used by Pz.Kpfw. III had a calibre of 50 mm, not 75 mm (“7, 5 cm”) as stated in the sources, while the Russian gun had a calibre of 152 mm, not 172 mm (“17,2 cm”).

15 Bieszanow W, Poligon... op. cit., p. 268-269.

16 Schramm P. E., op. cit., Teilband 1, p. 665.

17 Halder F., v III, op. cit., p. 622.

18 Halder F, v.III, op. cit., p. 623.

19 Schramm P. E., op. cit, Teilband 1, p. 677.

20 Hermann C. H., op. cit., p. 113.

21 Bieszanow W., Poligon... op. cit., p. 275.

22 Hermann C. H, op. cit., p. 114 and 172.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE CHART OF THE 9th PANZER DIVISION ON OCTOBER 23 1942

On September 22 Generaloberst Halder wrote: “Ongoing urgent phone conversations with Generalfeldmarschall von Kluge, who now does not believe again in the effectiveness of advance on Nielidovo, so he intends to use the 95th Infantry Division and the 9th Pz. Div. against Vasiuga.”23

On September 29, the 9th Division, assigned as a reserve of the Army Group “Mitte” and the 9th Army (AOK 9), was directed by way of Smolensk to the region of Sychevka. After arrival, Generalleutnant Scheller ordered construction of roads, barracks and an all-round fortified defensive zone. A lot of time and attention was devoted to training and local reconnaissance.24 During this pause in action, the combat potential of the unit was restored.

On September 30, the 33rd Panzer Regiment could field 91 tanks.

The region of Sychevka. lies in the so-called Rzhev salient. The area was particularly convenient as a base for the next potential attack on Moscow. This factor, as well as prestige reasons, motivated the Germans to keep a stronghold there, despite the significant extension of the front lines. A note in the “Kriegstagebuch” of OKW dated October 5 reveals: “Army Group “Mitte” has in the 9th Army operational area the “Grossdeutschland” Motorised Infantry Division (Infanterie-Division “Grossdeutschland” (mot)), the 9th Panzer Division and other local reserves.”25

On October 23, the 60th Panzer Division Supply Command was reorganized into 60th Command of the Panzer Divisions Supply Troops (Kommandeur der Panzerdivision-Nachschubtruppen 60 - Kdr. der Panzer-Div.Nachschubtruppen 60). Between October and November, the German high command reassessed the exact location of the 9th Division units within the Rzhev salient.

On November 16, the entry in the “Kriegstagebuch” of OKW lists one possible location: “The 1st and the 9th Panzer Divisions should first be positioned in the area west of Zubtsov.”26

According to a report from November 18, the 9th Panzer Division from the 9th Army of the Army Group “Mitte” was equipped with 26 Pz.Kpfw. II tanks, 30 Pz.Kpfw. III armed with 50 mm short barrel guns, 32 Pz.Kpfw. III armed with 50 mm long barrel guns, seven Pz.Kpfw. IV armed with 75 mm short barrel guns, five Pz.Kpfw. IV armed with 75 mm long barrel guns and two Pz.Bef.Wg.27.

25 November 1942 marked the beginning of operation “Mars”, the offensive on the Soviet Western Front and the Kalinin Front on the Rzhev salient. Marshal Zhukov hoped that just like in the Stalingrad battle, the German defenders will become trapped and will eventually be destroyed. The most vulnerable sector located in the east of the Rzhev salient, along the rivers Vazuza and Osuga, was manned by three German infantry divisions, 102nd, 337th and 78th (102., 337. and 78. Inf. Div.) supported by the 5th Panzer Division. At that time, the above units and the 9th Panzer Division were part of the XXXIX Armoured Corps (XXXIX PzK). The 9th Division was placed as an operational reserve west of Sychevka. The I Battalion of the 33rd Panzer Regiment, was an exception, as it was stationed on the other side of the Rzhev salient near the town of Belyy.

The region where the main divisional forces were stationed was attacked by two armies of the Western Front. The 20th and the 31st Army were deployed at the eastern end of the Rzhev salient, north of Zubtsov, at the 40 kilometres stretch along the rivers Vazuza and Osuga. The 20th Army consisted of the 247th Rifle Division, 80th and 140th Tank Brigades, and the 331st Rifle Division as a reserve. The 31st Army included the 88th, 336th and 239th Rifle Divisions, along with the 145th and 332nd Tank Brigades. The Russians were able to penetrate through the German defences and gain ground, reaching the Viazma-Rzhev railroad line. On the evening of November 25, the 9th Panzer Division was dispatched toward Russian bridgehead on the Vazuza River. On November 26, German reinforcements, parts of the XXVII Corps (XXVII AK) from Rzhev and the 9th Panzer Division from Sychevka, reached the area of the Soviet breakthrough. The 9th Division was then divided into two combat groups identified as “Kampfgruppe Remont” and “Kampfgruppe von Zettwitz”,28 according to the names of their commanders. M. D. Glantz quotes imprecise spelling of the names. “Kampfgruppe Reumont”, most likely consisted of 11th Panzer Grenadier Regiment led by Oberstleutnant Dr. Alfred von Reumont, while the core of the “Kampfgruppe Czettritz” was the 10th Panzer Grenadier Regiment under Hauptmann Gotthard von Czettritz und Neuhaus. According to M. D. Glantz, each combat group had 40 tanks, supply columns and panzer grenadier troops. The presence of tanks suggest that sub-units of the I and II Battalions of the 33rd Panzer Regiment were incorporated into the groups. Both groups were to advance up the Rzhev-Sychevka road towards the attacking Soviet vanguards. Unfortunately, both newly created groups reported that, at the earliest, their combat readiness could only be attained on the morning of November 27. However, Soviet advances made throughout the day forced the Germans to hastily create, and immediately deploy, a new group referred to as “Kampfgruppe Hochbaum”. This combat group, named after Oberst Wilhelm Hochbaum, commander of the 33rd Panzer Regiment, was ordered to attack the advancing Soviet Tank Corps under Colonel Arman. The first German counter-attacks hit the forefront as well as the flanks of the progressing Soviet tank formation. At 17:30, in diminishing daylight, a chaotic encounter took place south-west of Aristovo and along the sides of the Rzhev- Sychevka road. During this clash, the “Kampfgruppe Hochbaum” overwhelmed Soviet infantry grouped in the village of Bolshoye Kropotovo. The German assault crushed the 147th Rifle Division, thus Wehrmacht troops were able to proceed to the open fields east of the village. After Bolshoye Kropotovo was secured, Oberst Hochbaum spent the night at that location awaiting reports from the units deployed in the south. The 78th Infantry Division under General Völker, operating in that area, attempted to restore the defences in their sector of the front. The situation was tense due to the constant Soviet Army onslaught. With help from the 9th Panzer Division, efforts were made to liquidate the breaches made by the enemy. In the afternoon, one of the battalions from the 9th Division, along with some sub-units of the 13th and 14th Panzer Grenadier Regiments (Pz.Gr.Rgt. 13 and 14) from the 5th Panzer Division, was able to re-establish a continuous defensive front between the villages of Zherebtsovo and Khlepen. It was made possible by countering the attacks conducted by the 8th Guards Rifle Corps. Meanwhile, “Kampfgruppe Reumont” was preparing for an attack north along the Rzhev- Sychyeka road against Soviet tank units active in the area. In the late afternoon, adjusting to the dramatically changing situation, General von Arnim, commander of the XXXIX Armoured Corps, made another change to the command structure. Generalleutnant Scheller, commander of the 9th Panzer Division, was made responsible for the counter-attacks carried out against the main Soviet armoured forces operating along, and east of, the Rzhev- Sychevka road. As it turned out, all the German counter actions undertaken that evening were unsuccessful, partially due to the snow fall. Generally, on November 26 the Germans only narrowly avoided a catastrophic defeat. It was the chaotic actions of the attacking Soviet Army units that allowed the Wehrmacht to block enemy breaches.

Early in the morning of November 27, General von Arnim directed the 102nd Infantry Division located in the northern sector to abide by the orders from the 9th Panzer Division. The infantry was to protect the regions north of the Osuga River and between the Osuga and Vazuza rivers. The heaviest Soviet assaults of that day were directed against the German defensive positions in the vicinity of Nikonovo. At 9:15, “Kampfgruppe Hochbaum” 29 reported that the Soviet offensive had forced the group to abandon the defence of Novaya Grinevka village, and withdraw to Nikonovo. Furthermore, Oberst Hochbaum warned that the testimony of Russian prisoners and deserters indicate preparations for a massive offensive to commence in the area that very morning. The attack was to be conducted by the 2nd Guards Cavalry Corps. In an effort to thwart that threat and weaken Soviet pressure on Khlepen township, the newly created Combat Group “Scheller” (“Kampfgruppe Scheller”), named after Generalleutnant Scheller, was to launch an attack towards Aristovo. It was expected that the south flank of the Soviet offensive forces could be found in that general area. As the day went by, the German situation worsened. At 13:00 hours the Soviet forces began another attack, most likely the 20th Cavalry Division that sent its units in a two-pronged formation from Novaya Grinevka and Aristovo towards Nikonovo. As the telephone lines were not functioning, Oberst von Bodenhausen from the 31st Panzer Regiment of the 5th Panzer Division sent a radio message: “Heavy tank attacks from the east and south have made the situation very serious.”30 Soon after, the 9th Panzer Division reported via radio: “Group Hochbaum’s tank attacks on Aristovo are a failure. Eighteen enemy tanks are destroyed and eight of ours are lost. Many other of our tanks are damaged, but they can be brought home.”31 The reminder of “Gruppe Hochbaum” fought its way through Russian lines and joined Oberst von Bodenhausen’s forces. The German units, under heavy artillery fire, had to fend off successive Soviet attacks. The first one was carried out by the 247th Rifle Division, the subsequent one by the newly-arrived 1st Guards Motorised Rifle Division. Despite a very difficult situation, the combat groups dispatched from the 9th Panzer Division were able to stop the reserve units of the 20th Army deployed into action. The 22nd and the 200th Tank Brigades, supported by units of the 6th Motorised Rifle Brigade, came to a standstill at the outskirts of Soustovo, Azarovo and Nikishyno, northeast of Sychevka.

On November 28, the Russians began operations as early as 4 o’clock in the morning. At Nikonovo, Combat Group “von Bodenhausen” (“Kampfgruppe von Bodenhausen”) came under heavy attack. At 5:50, the I Battalion of the 430th Grenadier Regiment (I/Gr.Rgt. 430) reached the village of Podosinovka. General von Arnim ordered the battalion to support the 9th Panzer Division tanks in a northward attack launched at dawn against the south flank of advancing Soviet troops. Before the attack commenced, units of the Red Army began their own assault on Podosinovka. Russian tanks, infantry and cavalry forced the Germans to assume defensive positions. The clash lasted throughout the day without resolution. “Combat Journal of the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces” reflects the events of the day: “The 9th Army’s front is under continuous enemy attacks (…) Northeast of Sychevka the 9th Panzer Division joins the encounter. A tank battle ensues, during which 56 enemy tanks are destroyed.” 32 In the evening, General von Arnim ordered the 9th Panzer Division to muster men from the quartermaster and support units as well as convalescents, to create reserve troops. By November 30, these soldiers, as the 5th Panzer Division reserve units, were to be positioned at the defence lines. By the end of the day, the possibility of encircling Soviet troops, which managed to break through the German lines, became apparent.

During the night of November 29, the Germans attacked the flank and the rear of the Soviet group, which breached the defences. The units of the XXVII Corps attacked from the north, while the XXXXIV Armoured Corps with the 9th Panzer Division at the forefront moved in from the south. This manoeuvre allowed the Wehrmacht to close the gaps made by the Soviets in the German defence front at the vicinity of Lozkhi and Nikonovo. The combat groups dispatched from the 9th Panzer Division were involved in series of encounters, but did manage to advance through Bolshoe and Maloe Kropotovo, Nikonovo, Aristovo and Podosinovka. Additionally, in the same area, located east of the Rzhev-Sychevka railway line, the German forces managed to sack a group of 20th Army units. Among these units were parts of the 2nd Cavalry Corps, 22nd and 200th Tank Brigades, some 6th Motorised Rifle Brigade’s battalions and the remnants of the 1st Bicycle -Motorcycle Brigade. The 9th Panzer Division’s combat groups continued with their advance towards Nikonovo and Belokhvostovo south of Lozkhi, under constant counter-attacks by Soviet troops from the inside as well as the outside of the sack.

On November 30 1942 the crisis at Nikonovo, Bolshoe and Maloe Kropotovo continued. The 1st Guards Motorised Rifle Division and the 29th Guards Rifle Division persisted with their tank and infantry attacks until the Soviet riflemen managed to break into Nikonovo. The German units were forced to abandon their positions. During the onslaught, Oberst Hochbaum was seriously wounded. In the late afternoon, the II Battalion of the 430th Grenadier Regiment (II/Gr.Rgt. 430) managed to recapture Nikonovo in a successful attack. The entry made in the “Kriegstagebuch” of OKW on that day states: “Army Group “Mitte”: between Sychevka and Rzhev enemy breakthrough successful in the area of 9 Pz. Div. Counterattack in progress.”33 On the same day, the 9th Panzer Division was able to recapture and secure the Rzhev-Sychevka railroad line, by some German accounts referred to as a “lifeline” of the 9th Army. Indeed, this line, extending to Viazma, allowed for efficient transport of all supplies for Generaloberst Model’s army. The combat was very intense; the Red Army sustained heavy losses and lost many tanks.34

During the night of November 30, a breakout attempt by surrounded 20th Army units took place. Near Maloe Kropotovo, the 6th Tank Corps launched an attack from the east to support this action. On December 1, as a result of a very fierce fighting, during which the commander of the 200th Tank Brigade Colonel Vinakurov and political commissar Rybalko (who took over the helm of the 6th Motorised Rifle Brigade35 after the demise of its commander), both died, parts of the Soviet units manage to burst out of the pocket. The 6th Tank Corps attacking from the outside, had to be afterwards transferred to the reserve due to heavy losses.

The “Kriegstagebuch” of OKW under the date of December 1 communicates: “Army Group “Mitte”: as of yesterday no unusual combat activities in the Rzhev region. The railroad line between Rzhev and Sychevka is being cleared of enemy troops form the south by the 9. Pz.Div and from the north by the 129th Infantry Division (129. Inf.Div.).”36

The 9th Panzer Division was transported by train to the Orel region. An NCO along with an Oberleutnant in a passenger compartment. Medal ribbons are noteworthy.

As the rail line was secured, the 9th Panzer Division continued to fight northeast of the divisional supply base located in Sychevka. The major combat activities in the area of Vazuza subsided by December 4. On December 10, General Robert Martinek, the newly appointed commander of the XXXIX Armoured Corps, assigned the task of defending Vazuza to the 9th Panzer Division and the 78th Infantry Division. He also ordered strengthening of the defence positions. The 9th Panzer Division created a strong and deep defensive zone between the south bank of the Osuga River and Maloe Kropotovo, anchored around the fortified villages of Bolshoe Kropotovo and Maloe Kropotovo.37 Local skirmishes in that area lasted until December 18.

As mentioned before, on November 25 the 22nd and the 41st Armies of the Kalinin Front began an offensive on the western segment of the Rzhev salient. The 41st Army’s attack targeted the town of Belyy, while the 22nd Army marched from the north along the Luchesa River. The Belyy area was defended by the “Kampfgruppe von Wietersheim” created on November 25. The group consisted of the II Battalion of the 113th Panzer Grenadiers Regiment (II./Pz.Gr.Rgt. 113) supported by the II Detachment of the 73rd Armoured Artillery Regiment (II./Pz.Art.Rgt. 73) and the I Battalion of the 33rd Panzer Regiment.38

On the opening day of the offensive, the counter attack carried out by the II Battalion of the 1st Panzer Grenadiers Regiment (II./Pz.Gr.Rgt. 1) from the 1st Panzer Division under Oberst von der Meden, managed to free a tank company of the 33rd Panzer Regiment, which fought throughout the day surrounded by the enemy in the village of Shamilovo, west of Shtepanovo. The unit, with the aid of eight damaged tanks, managed to repel all Soviet attacks. On November 30, the area breached by the Kalinin Front forces was reached by all available forces of the 9th and the 12th Panzer Divisions. Thus, on December 1 the Soviet 1st Motorised Corps led by General Solomatin, was forced into the defensive. It was evident that during the defence of Rzhev salient the units of the 9th Panzer Division for most part operated independently of each other, just like the I Battalion of the 33rd Panzer Regiment mentioned above. On December 14, during a joint action of the 33rd Panzer Regiment and the 12th Panzer Division units, a Pz.Kpfw. III tank armed with Kwk. 39 L/60 50 millimetre gun sustained a hit. An anti-tank shell burst at the front observation view ports of the driver and machine gunner. Trooper Enke was killed, Schmidt, Ewald and Betz were wounded, whereas Fahnenjunker Ludwig Bauer managed to survive unharmed.39

An order dated December 15 dissolved the 9th Panzer Grenadier Brigade. On December 18, 1942, Generaloberst Model transferred the 9th Panzer Division to the north of the Rzhev salient. It was assigned to the “Burdach” Group of the XXVI Corps (“Gruppe Burdach” XXVI AK) led by Generalmajor Karl Burdach, commander of the 251st Infantry Division (251. Inf.Div.). Besides the 9th Panzer Division, the group consisted of 87th Infantry Division (87. Inf.Div.), 251st Infantry Division and solitary units of the 6th and 206th Infantry Divisions (6. and 206. Inf.Div).

At the beginning of 1943 combat groups of the 9th Panzer Division held positions in the Zaitsevo and Panovo townships, where under different weather conditions, humid, cold wind or sunny skies, they resisted enemy attacks or conducted counter-attacks.40 At that time, the 33rd Panzer Regiment was weakened by a withdrawal of the II Battalion, transferred to Grafenwöhr in Germany. Once there, the unit was equipped with new Pz.Kpfw. V Panther tanks and re-designated as the Panzerabteilung 51 (Pz.Abt. 51) - Army Troop (Heerestruppe) in accordance to an order issued on January 13 1943.

Until February 7, the 9th Panzer Division participated in the defence of Rzhev. It remained within the “Burdach” group until February 12.41 In the meantime, the newly created Corps “Scheele” (Korps “Scheele”) led by General der Infanterie Hans-Karl von Scheele, deployed north of Zhizdra, was in need of immediate assistance due to concentrated Soviet attacks. The 9th Panzer Division was assigned that task, so it had to be withdrawn from the front lines and directed west of Belyy. After reaching the town on February 25, the Division had to perform a 650 kilometre road march through Viazma, Smolensk, Roslavl and Briansk. It was a challenging stretch even though some of the distance was travelled by rail. By the end of February, the Division managed to reach the area threatened by Soviet forces.42 Upon arrival north of Zhizdra, the 9th Panzer Division was immediately drawn into a four week long battle lasting throughout March 1943.43

Wooden anti-aircraft tower near the railway crossing, probably at Poltava. The photograph taken during the transfer of the 9. Pz.Div. away from the front, so it could recuperate before the “Citadel ” operation.

Due to a Soviet breakthrough, the entire Division, in a state of emergency equivalent to that of a fire-fighter squad, was deployed to the general vicinity of Volkovo, in the region between the townships of Jesenok-Dubishtche-Askovo, as early as March 1. In the following few days, the Division fought heavy defensive battles, launching frequent counter-attacks carried out mostly by the 33rd Panzer Regiment and the I battalion of the 10th Panzer Grenadier Regiment. A large number of Soviet prisoners were taken during these encounters.44

On March 7, Major Gerard Willing, commander of the III Battalion of the 33rd Panzer Regiment, was decorated with the Knight’s Cross.45

The remainder of the 9th Panzer Division units, including the 11th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, the 59th Motorcycle Rifle Battalion, the 86th Armoured Pioneer Battalion and the 50th Tank Destroyer Battalion fought as regular infantry units. Whenever possible, the units attempted to stay in close proximity to the tanks of the 33rd Panzer Regiment, particularly during the heavy fighting in the so called “Gorn forest” (“Gornwald”) on the northern bank of the Jasenok River.46 This wooded area, named after Oberst Gorn, commander of the 10th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, for half a month became a scene of extremely fierce battles with frequent occurrences of hand to hand combat - recalls C. H. Hermann in his book “Die 9. Panzer-Division 1939-1945”.

The photographs taken during that time indicate that the 9th Panzer Division was using an emblem, most likely a temporary one. On one of the photographs, it is displayed on a panel next to the “Schmahl” inscription, referring to Oberst Ludwig Schmahl, the leader of the 33rd Panzer Regiment. It is possible that the use of the emblem was restricted to either the 33rd Regiment, or one of the temporary combat groups. On the other hand, it is not unlikely that it was adopted for the entire division, to mislead the enemy into believing that a new unit had arrived to reinforce the front. On the panel mentioned above, a fire-fighter equipped with a fire hose may be noticed. It probably referred to the role of the 9th Panzer Division, used in the critical areas of the front as a fire brigade would be used in extinguishing fires.

An order to withdraw another battalion from the 33rd Panzer Regiment was issued on March 15, this time it was the III Battalion. On April 3, the troops boarded a train in the town Orel and travelled to St. Pölten, Austria. The battalion was transformed into the 506th Heavy Tank Battalion (schwere Pz.Abt. 506) armed with Pz.Kpfw. VI Tiger tanks on May 8.47.

Meanwhile, an order dated March 16 initiated formation of a new armoured reconnaissance battalion for the 9th Panzer Division. The battalion, most likely stationed in Bruck an der Leitha, Austria, was to achieve combat readiness by April 20 1943.

Beginning on March 18, the number of Red Army attacks north of Zhizdra diminished.48 On March 26, Unteroffizier Heinrich Hendricks from the 9th Company of the 33rd Panzer Regiment49 became another recipient of the Ritterkreuz, a few day later, on March 31, Unteroffizier Leopold Liehl from the 7th Company of the 10th Panzer Grenadiers Regiment received the same honour.50

The Oberkommando der Wehrmacht was quite willing to show due recognition to the 9th Panzer Division for its efforts in March 1943. On April 3 Generalleutnant Walter Scheller, the commander, became the 21st divisional recipient of the Ritterkreuz. On the same occasion, Oberleutnant Fritz Jacoby from the 7th Company of the 11th Panzer Grenadier Regiment51 was also decorated. Overall, for the actions at Zhizdra the soldiers of the 9th Panzer Division received five Knight’s Crosses, 13 German Crosses in Gold (Deutsche Kreuz in Gold), 213 Iron Crosses I class (Eisernen Kreuz I Klasse) and 1,545 Iron Crosses II class (Eisernen Kreuz II Klasse). Two more soldiers were listed in the Honour Roll of the German Army (Ehrenblattnennung).52 On the other side of the bloody battles were the hundreds of soldiers buried at Zhizdra cemetery.53

An officer of the 102nd Panzer Artillery Regiment, most likely in a rank of Leutnant , decorated with Allge-meinesturmabzeichen .An Iron Cross as well as the Winterschlacht im Osten (Eastern Front Medal) ribbons are also visible.

On April 20, the entire 9th Division was withdrawn from active duties and, as a reserve of Army Group “Mitte”, was concentrated in the region of Briansk and Karatschev to allow for reorganization, training, replenishing of equipment and well-deserved rest. On that day, Feldwebel Wilhelm Steger from the 6th Company of the 10th Panzer Grenadier Regiment received the Ritterkreuz.

In the meantime, the high command assigned the Division to the 2nd Panzer Army for the purpose of the new offensive, code-named operation “Zitadelle” (“Citadel”), planned for the summer. Therefore, on April 25, the Division was ordered to relocate to the vicinity of Orel. The first rail transports to the new concentration point departed the very same day. Once the destination was reached, intensive training commenced. Generalleutnant Scheller’s goal was to increase the coordination level between sub-units fulfilling the same objective. As one of the exercises, with a practical purpose of improving the supply route, the 1st Company of the 86th Armoured Pioneer Battalion constructed a 24 ton capacity wooden bridge. The weeks of relatively warm spring weather were spent not just on exercises. Week long rest periods were allowed in a specially established divisional recreation centre, named “General-Scheller-Heim” (“House of General Scheller”) at the township of Dobromo. Amateur theatre spectacles with Russian folk music concerts were regularly given at Smiyevo.

The 9th Panzer Division transported by train to the Orel region.

Three officers from different 9th Division’s units. The Major , first from the left, was decorated with the Deutsches Kreuz in Gold, the Leutnant , most likely from the Panzer Grenadier Regiment has the Eisernes Kreuz I klasse and the Infanterie-Sturmabzeichen (Infantry Assault Badge) and the Oberleutnant , probably an artillery officer, E isernes Kreuz I klasse as well as Allgemeinesturmabzeichen .Two latter officers were also decorated with the Winterschlacht im Osten medals.

During that time, some new organizational changes took place. According to the order issued on April 20,54 the IV Detachment of the 102nd Armoured Artillery Regiment was restored to its original designation of the 287th Land Forces Anti-aircraft Artillery Detachment. On May 5, the 3rd Anti-aircraft company of the 50th Armoured Tank Destroyer Battalion (3(Flak)/Pz.Jg.Abt. 50) was re-designated as the 4th Company of the 287th Land Forces Anti-aircraft Artillery Detachment (4/H.Flakart.Abt. 287). The order dated May 7 converted the II Detachment of the 102nd Armoured Artillery Regiment into a self-propelled artillery detachment. Additional changes took place on June 13. The 9th Company of the 10th Panzer Grenadier Regiment and the 9th Company of the 11th Panzer Grenadier Regiment were transformed into self-propelled units. At the same time, the 701st Company of Heavy Infantry Guns, integrated into the 9th Division in the spring of 1940, was dissolved and absorbed by the self-propelled companies listed above. As the day of the summer offensive at the Kursk bend approached, the new 9th Armoured Reconnaissance Battalion (Pz.Aufk.Abt. 9)55 joined the Division on May 27. As stated before, this unit was drafted on March 16, with the expected readiness for April 20.56 It comprised the headquarters, two light armoured reconnaissance companies (lePz.Aufk.Kp. (gep)) and one heavy, partially armoured, reconnaissance company (sPz.Aufk.Kp. (tgep)). It was planned that the remnants of the 59th Battalion of Motorcycle Rifles were to be incorporated into the 9th Armoured Reconnaissance Battalion as well. However, as an interim measure, an order issued on April 19 added a company of Armoured Reconnaissance Vehicles “b” (Panzer-Spähwagen-Kompanie “b” (Pz.Spah.Kp. “b”)) to the 9thArmoured Reconnaissance Battalion. The company was equipped with the reconnaissance tanks designated as Panzerspähwagen II Ausf. L (Sd.Kfz. 123) “Luchs”(“Lynx”).

An artillery Leutnant awarded the Eisernes Kreuz I klasse. In the background an artillery observation tank Artillerie Panzerbeobachtungswagen III Ausf. G (Sd.Kfz. 143) assigned to the II Squadron of the 102nd Armoured Artillery Regiment.

The same officer in front of an Artillerie Panzerbeobachtungswagen III. The vehicle has a modified gun mantlet. The dummy gun barrel is on the right hand side, while a MG 34 machine gun mount is visible in the centre. The tank was equipped with the FuG 4 and FuG 8 radio communication transmitters. A retractable TUF 2 periscope may be seen on the turret.

The same Artillerie Panzerbeobachtungswagen III Ausf. G in factory paint scheme, soon after the arrival to the Division. Only standard Wehrmacht markings, the Balkenkreuz, are painted on the tank. The vehicle does not have a machine gun in the turret. The frontal armour has a 30 mm reinforcing layer, and the machine gun ball mount in the hull was eliminated.

According to the original plan, the company was to become the 5th Company of the 9th Armoured Reconnaissance Battalion, but later this designation was changed to the 2nd Company. The Armoured Reconnaissance Vehicles Company “b” was established according to the order issued on February 23 1943. It was the first Wehrmacht unit to be equipped with the “Luchs” tanks. The company had 18 tanks of this type. Formation of the unit took place in France; its combat readiness was attained on March 25 1943.57 At first, it was intended to join the 10th Panzer Division,58 or according to other sources the 9th SS Panzer Grenadiers Division (9. SS-Pz. Gren.Div.).59 At the beginning of April 1943, it was decided that the “Luchs” company would be assigned to the 9th Panzer Division. The official identifier of this sub-unit from April 30 was the 2nd Panzer Reconnaissance Company of the 9th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion (2. Panzer-Späh-Kompanie/Pz.Aufkl.Abt. 9).60 On April 26, the company was dispatched from France to Germany so it could join the rest of the recently formed reconnaissance battalion. An order dated May 4 requested the transfer of the 9th Armoured Reconnaissance Battalion, including the newly formed Pz.Spah.Kp. “b”, from Bruck an der Leitha to Army Group “South” to commence on May 11. As the battalion reached Orel, it was most likely reinforced with the remainder of the 59th Motorcycle Rifle Battalion.

Apart from the “Luchs” company, the 9th Armoured Reconnaissance Battalion had two reconnaissance companies equipped with half-tracked armoured transporters Sd.Kfz. 250, a reconnaissance platoon with Schwimmwagen amphibious all-terrain cars, and some heavy self-propelled anti-tank guns, most likely of sPak. (Sfl) “Marder” type. As of June 1943, the 2nd Company of the 9th Armoured Reconnaissance Battalion had at its disposal 29 “Luchs” tanks and four armoured transporters Sd.Kfz. 251/1. Beginning in May 1943 the 9th Panzer Division, apart from the reconnaissance tanks mentioned above and typical equipment replacements, received some new types of combat ordnance. According to R. Stoves, the I Battalion of the 10th Panzer Grenadier Regiment and the 3rd Company of the 8th Armoured Pioneer Battalion received some half-tracked armoured transporters Sd.Kfz. 251, while the 287th Land Forces Anti-aircraft Artillery Detachment obtained three new batteries armed with a total of twelve 88 mm anti-aircraft guns.61 In the same month, the Division acquired four heavy armoured reconnaissance vehicles, most likely the eight-wheel version, and six medium half-tracked armoured transporters Sd.Kfz. 251/16 armed with flamethrowers. As this equipment arrived, a flame thrower platoon (Flamm-Zug (gep)), was created on May 13. The platoon was assigned to the headquarters company of the 10th Panzer Grenadier Regiment. In June, the 9th Division acquired an additional 26 Pz.Kpfw. IV tanks62 and one half-tracked transporter.63 At the same time, the II Detachment of the 102nd Armoured Artillery Regiment was equipped with the new self-propelled 15 cm heavy howitzers - schwere Panzerhaubitze sFH 18/1 auf Geschützwagen III/IV Sd.Kfz. 165 “Hummel” (“Bumble bee”), and self-propelled light howitzers - leichte Feldhaubitze 18/2 (sf) auf Geschützwagen II “Wespe” (“Wasp”). In July there were twelve “Wespe” howitzers on the divisional roster.

As for other new equipment, a few artillery observation vehicles - Artillerie Panzerbeobachtungswagen III Ausf. G, Sd.Kfz. 143 - were assigned to either the II Detachment of the 102nd Armoured Artillery Regiment, or the 102nd Armoured Observation Battery.

The presentation of the new equipment took place on June 12, as the 9th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion paraded in front of the XXXXVIII Armoured Corps’ commander, General der Panzertruppe Joachim Lemelsen.

Photographs published in Mr. Hermann’s book indicate that the 9th Panzer Division obtained half-tracked armoured transporters Sd.Kfz. 250, and some eight wheeled armoured reconnaissance vehicles Sd.Kfz. 231 as well as their derivative, the Sd.Kfz. 233 armed with a short barrel 75 mm gun. In the meantime, on July 8, Oberst Gorn, commander of the 10th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, received the Oak Leaves and Swords with his Knight’s Iron Cross.64 This decoration was awarded for his stance during the March combat at Zhizdra, he was just the 30th Wehrmacht soldier recognized in such a way. As mentioned before, two tank battalions were withdrawn from the 33rd Panzer Regiment, so by that time the 9th Panzer Division had only a single tank battalion.

As of July 1 1943, the divisional order of battle was as follows:

Stab/9. Panzer-Division - 9th Panzer Division Headquarters, consisting of:

Div.Kdo. [Divisionskommando] - Divisional Command

Div.Kart.St. (mot) 60. [Divisionskartenstelle] - Divisional Mapping Detachment, motorised

Pz.Rgt. 33 - 33rd Panzer Regiment, consisting of:

Stab - Headquarters

I. Abt. [Abteilung]- I Battalion

Stab included:

Pz.Na-Zug, [Panzer-Nachrichten-Zug] - Armoured Signal Platoon

Pz.Aufk-Zug [Panzer Aufklärungs-Zug]- Armoured Reconnaissance Platoon

Pz.Werk.Kp. (0./2. Zug) [Panzerwerkstatt-Kompanie (ohne 2. Zug)] - Repair (maintenance)

Company without Second Platoon

I. Abteilung had:

Stab - Headquarters

Stab.Kp. [Kompanie] - Headquarters / Staff Company

three (1., 2., 3.) lePz.Kp. [leicht Panzer Kompanie] - Light Tank / Armoured Company

one (4.) mPz.Kp. [mittlere Panzer Kompanie] - Medium Tank / Armoured Company

Panzergrenadier-Regiment 10 (gep) [gepanzerte] - 10th Panzer Grenadier Regiment (armoured) included:

Stab - Headquarters

I. Bataillon (gep) - I Battalion (armoured)

II. Bataillon (mot) - II Battalion (motorised)

Stab had:

Stab.Kp (tgep) [teil-gepanzerte] - Headquarters / Staff Company (partially armoured)

(9.)sIG. Kp (Sf) [schwer Infanterie-Geschütz (selbstfahr)] - Heavy Infantry Gun Company

(self-propelled)

(10.) Flak Kp. (Sf) [Flugabwehrkanone] - Anti-Aircraft Company (self-propelled)

Flamm-Zug (gep) - Flame Thrower Platoon (armoured)

I. Bataillon consisted of:

Stab - Headquarters

three (1., 2., 3.) Pz.Gren.Kp. [Panzergrenadier-Kompanie] - Panzer Grenadier Company

one 4. sPz.Gren.Kp. (gep) - Heavy Panzer Grenadier Company (armoured)

II. Bataillon consisted of:

Stab - Headquarters

three (5., 6., 7.) Pz.Gren.Kp.(mot) - Panzer Grenadier Company (motorised)

one 8. sPz.Gren.Kp. - Heavy Panzer Grenadier Company

Panzergrenadier-Regiment 11 - 11th Panzer Grenadier Regiment consisted of:

Stab - Headquarters

I. Bataillon (mot) - I Battalion (motorised)

II. Bataillon (mot) - II Battalion (motorised)

Stab included:

Stab.Kp.(mot) - Headquarters / Staff Company (motorised)

(9.) sIG.Kp (Sf)65 - Heavy Infantry Gun Company (self-propelled)

(10.) Flak Kp. (Sf). - Anti-Aircraft Company (self-propelled)

I. Bataillon had:

Stab - Headquarters

three (1., 2., 3.) Pz.Gren.Kp. (mot) - Panzer Grenadier Company (motorised)

one (4.) sPz.Gren.Kp. (gep) - Heavy Panzer Grenadier Company (armoured)

II. Bataillon had:

Stab - Headquarters

three (5., 6., 7.) Pz.Gren.Kp .(mot) - Panzer Grenadier Company (motorised)

one (8.) sPz.Gren.Kp. (mot) - Heavy Panzer Grenadier Company (motorised)

Panzer-Artillerie-Regiment 102 consisted of:

Stab - Headquarters

I.Abt. [Abteilung] - I Artillery Detachment (battalion)

II.Abt. (Sf) - II Artillery Detachment (battalion) (self-propelled)

III Abt.(s) - III Artillery Detachment (battalion) (heavy)

Stab had:

Stab.Bttr. (mot) [Batterie] - Headquarters/Staff Battery (motorised)

Pz.Beob.Bttr. (mot) 102 [Beobachtung Batterie] - Armoured Observation Battery (motorised)

I. Abteilung included:

Stab - Headquarters

Stab.Bttr (mot) - Headquarters / Staff Battery (motorised)

three (1., 2., 3.) Bttr. leFH. (mot Z) [leicht Feldhaubitze (motorisiert mit Zugmachine)] - Light

Field Howitzer Battery (motorised tow traction)

II. Abteilung included:

Stab - Headquarters

Stab.Bttr. (gep) - Headquarters / Staff Battery (armoured)

two (4., 5.) Bttr. leFH. (Sfl)[Selbstfahrlafette] - Light Field Howitzer Battery (self-propelled tracked carriage) equipped with “Wespe” vehicles

one (6.) Bttr. sFH (Sfl) - Heavy Field Howitzer Battery (self-propelled tracked carriage)

equipped with “Hummel” vehicles

III. Abteilung included:

Stab - Headquarters

Stab.Bttr. (mot) - Headquarters/Staff Battery (motorised)

one (7.) Bttr. 10,5-cm sK (mot Z [schwer Kanone (motorisiert mit Zugmachine)] - Heavy

Field Gun Battery (motorised tow traction)

two (8., 9.) Bttr. sFH. (mot Z) - Heavy Field Howitzer Battery (motorised tow traction)

Heeres-Flakartillerie-Abt. 287 - Battalion of Anti-aircraft Artillery of the Ground Forces consisted of:

Stab - Headquarters

Stab.Bttr. (mot) - Headquarters/Staff Battery (motorised)

two (1., 2.) sFlak-Bttr. (mot Z) - Heavy Anti-aircraft Battery (motorised tow traction)

one (3.) leFlak-Bttr. - 2 cm Flak (mot Z) - Light Anti-aircraft Battery (motorised tow traction)

one (4.) leFlak-Bttr. - 2 cm Flak (Sfl) - Light Anti-aircraft Battery (self-propelled tracked carriage)

one 2 cm Flak-Vierl (Sfl) [Flakvierling] - Quad anti-aircraft gun (self-propelled tracked carriage)

leArt.Kol. (20 t) [Artillerie Kolonne] - Light Artillery Column (20 ton)

one Scheinw. Stf (mot) [Scheinwerfer-Staffel] - Searchlight Section, motorised as part of the 3.

Bttr.

Panzerjäger-Abteilung 50 - Tank Destroyer (anti-tank) Battalion consisted of:

Stab - Headquarters

two (1., 2.) Pz.Jg.Kp. (Sf) - Tank Destroyer Company (self-propelled)

one (3.) Pz.Jg.Kp. (mot Z) - Tank Destroyer Company (motorised tow traction)

Panzer-Aufklärungs-Abteilung 9 - Armoured Reconnaissance Battalion included:

Stab - Headquarters

one (1.) Pz.Spah.Kp. [Panzerspäh-Kompanie] - Armoured Scout Vehicle Company including sPz.Spah-Zug [schwerer Panzerspäh-Zug] - Heavy Armoured Scout Vehicle Platoon equipped with Sd.Kfz. 233

one (2.) Pz.Spah.Kp. “b” - Armoured Reconnaissance Vehicle Company “b” equipped with PzKpfw. II Ausf. L

one (4.) lePz.Aufk.Kp. (gep) - Light Armoured Reconnaissance Company (armoured)

one (5.) sPz.Aufk.Kp. (gep) - Heavy Armoured Reconnaissance Company (armoured)

one lePz.Aufk.Kol. (mot) - Light Reconnaissance Column (motorised)

Panzer-Pionier-Bataillon 86 - Armoured Pioneer Battalion included:

Stab - Headquarters

two 1., 2. Pi.Kp. (mot)[ Pionier] - Pioneer Company (motorised)

one (3.) Pi.Kp. (gep) - Pioneer Company (armoured)

Brücke-Kol. “K” 86 - Bridge Column

one lePi.Kol. (mot) - Light Pioneer Column (motorised)

Panzer-Nachrichten Abteilung 85 - Armoured Communications Battalion included:

Stab - Headquarters

one (1.) Pz.Fsp.Kp.[Panzer Fernsprechkompanie] - Armoured Telephone-communications Company

one (2.) Pz.Fu.Kp.[Panzer Funkkompanie]- Armoured Radio-communications Company

one lePz.Na.Kol. (mot). [leichte Panzer-Nachrichten-Kolonne] - Light Armoured Signal Transportation Column

Feldersatz-Bataillon 60 - Field replacement Battalion consisted of:

Stab - Headquarters

four 1., 2., 3., 4. FE.KP (fsbw) [Feldersatz-Kompanie] - Field Replacement Company

one Div.K-Schule [Divisions-Kampfschule] - Divisional Combat School

Komandeur-Divisions-Nachschub Truppen 60 - Command of the Panzer Divisions Supply Troops included:

Stab - Headquarters

three 1./60, 2./60, 3./60 Kf.Kp. (120 t) [Kraftfahr] - Motor Transport Company (120 tons)

two 4./60, 5/60 Kf.Kp. (90 t) - Motor Transport Company (90 tons)

one 60 Fahr-Schw. (60 t) [Fahr-Schwadron] - Horse-drawn squadron (60 tons)

one 60. Nach.Kp. (mot) [Nachschub] - Supply Company (motorised)

Kraftfahrpark Truppen 60 - Vehicle Park Troops had three companies:

1./60, 2./60, 3./60 Werk.Kp. (mot) [Werkstatt-Kompanie] - Workshop / Maintenance Company (motorised)

one (60.) bew. Nach.Stf.ETle. (75 t) [Staffel fur Ersatzteile] - Spare Parts Supply Column

Verwaltungs Truppen 60 - Administration Troops included three companies:

Bä.Kp. (mot) 60 [Bäkerei-Kompanie] - Bakery Company (motorised)

Schl.Kp. (mot) 60 [ Schlachterei-Kompanie] - Butcher Company (motorised)

Va. (mot) 60 [Verpfegungsamt] - Ration’s Administration Detachment

Sanitäts Truppen 60 - Medical Troops had:

1./60, 2./60 San.Kp. (mot)[ Sanitätskompanie] - Medical Company (motorised)

three 1./60, 2./60, 3./60 Kr.Kw-Zug (mot)[Krankenkraftwagenzug] - Ambulance Platoon (motorised)

one Tr Eg-Zug (mot) [Truppen-Entgiftungs-Zug] - Decontamination Platoon (motorised)

Feldgendarmerie Trupp 60 - Field Military Police Troops

Feldpostamt 60 - Field Post Office.66

The report dated July 1 lists the 9th Panzer Division troop shortfall as 238, and its losses as 501 soldiers. Out of the latter number, there were 16 dead, 9 wounded, 218 ill and 258 lost for other reasons. Troop replacements totalled 709, out of which there were 375 draftees and 334 convalescents.

The number of divisional tanks available on that day amounted to: 25 Pz.Kpfw. III operational, and three under repair; 34 Pz.Kpfw. IV plus two under repair. In addition, the 9th Division had 275 half-tracked armoured transporters, armoured vehicles and armoured observation vehicles, plus 13 under repair. In all, there were 288 armoured combat vehicles. There were also 17, including one undergoing repairs, heavy self-propelled anti-tank guns, most likely “Marder”; 46 heavy motor traction anti-tank guns (sPak. (mot. Z)),67 plus four under repair, and 46 guns (Art-Gesch), out of which one was undergoing maintenance.68.

According to T. Jentz, the ordinance of the 9th Panzer Division on July 1 1943 included: one Pz.Kpfw. II tank, eight Pz.Kpfw. III tanks armed with short barrel (L/42) 50 mm gun, 30 Pz.Kpfw. III armed with long barrel (L/60) 50 mm gun, eight Pz.Kpfw. IV armed with a short barrel 75 mm gun and 30 Pz.Kpfw IV tanks with a long barrel 75 mm gun, supplemented by six Pz.Bef. III.69 Thus, the main combat force included 38 Pz.Kpfw. III tanks and an equal number of the Pz.Kpfw. IV. Accordingly, it may be stated that a few days prior to operation “Zitadelle” the 9th Panzer Division was fully prepared for action, being almost at 100% of troop and equipment potential. The report filed on July 1 indicated the percentage of equipment in existence, versus the required allowance: Pz.Kpfw. III- 53%, Pz.Kpfw. IV - 257%, SPW and Pz.Spah.Wg. - 89 %, sPak. (Sfl) - 89%, mPak. (mot. Z) and sPak. (mot. Z) - 100 %, artillery - 92 %.70

Noteworthy is the surplus of Pz.Kpfw. IV tanks. According to the quota, the number should be 22, while in reality there were 38 tanks. At the onset of operation “Zitadelle”, a concentric attack on Kursk was to be launched both from the north and from the south. Army Group “Mitte” led by Generalfeldmarschall von Kluge, was to advance from its line of departure established east of Maloarkhangelsk. The group consisted of 15 infantry divisions, six panzer divisions and one motorised division. The 9th Army, led by Generaloberst Model, was supposed to break through the Soviet defences on a 40 km stretch of land between Orel and Kursk, more precisely between the villages of Gnilets and Butryki, at the junction of the Soviet 13th and 70th Army defence sectors. The XXXXVII Armoured Corps under General der Panzertruppe Lemelsen, positioned in the centre of the 9th Army, was composed of the 6th Infantry Division and the 2nd, 9th, and 20th Panzer Divisions. As the breakthrough was achieved, the attack was to unfold between the road and the railroad tracks leading to the town of Kursk, aiming towards the hills north of the town in order to make contact with the Army Group “South”.71 According to the details of the plan, the XXXXVII Armoured Corps would dispatch the 6th Infantry Division and the 20th Panzer Division, keeping the stronger 2nd and 9th Panzer Divisions in reserve until the Soviet defences were breached.72.

Operation “Zitadelle” was initiated on July 5 1943. On that day, one day prior to the deployment of the 9th Panzer Division, divisional chaplain Baumgärtner visited the encampments to perform religious services. One of the masses was held at Smiyevo, where the 86th Armoured Pioneer Battalion was stationed.73 Even though the fighting lasted throughout the night, the 6th Infantry Division and the 20th Panzer Division did not manage to penetrate the Soviet lines. Despite that, on the evening of July 5 Generaloberst Model: “Simply informed General Lemelsen of his decision (…), on the following day the 2nd and 9th Panzer Divisions were to join the combat, regardless of the earlier plan to deploy them only after a breakthrough was achieved.” 74

23 Halder F., v. III, op. cit, p. 634.

24 Hermann C H, op. cit, p. 115.

25 Schramm P. E, op. cit, p. 793.

26 Schramm P. E, Kriegstagesbuch des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht 1942, Teilband 2, Eine Dokumentation, p. 967.

27 Jentz T. L, Die deutsche Panzertruppen 1943-1945, Band II, Wölfersheim-Berstadt, 1999, p. 24.

28 Glantz D. M., Zhukov’s greatest defeat. The Red Army’s epic disaster in Operation Mars, 1942, Lawrence, Kansas 1999

29 Glantz cites “General Hochbaum’s”. Hochbaum had a rank of Oberst at the time.

30 Glantz D. M., op. cit., p. 100.

31 Ibidem.

32 Schramm P. E., op. cit., Teilband 2, p. 1043.

33 Schramm P. E., op. cit., Teilband 2, p. 1057.

34 Hermann C. H., op. cit., p. 117-119.

35 Glantz D. M., op.cit., p. 185.

36 Schramm P. E, op. cit., Teilband 2, p. 1064.

37 Glantz D. M., op.cit., p. 259.

38 Battistelli P. P., Panzer Division: The Eastern Front 1941-43, Botley, Oxford, p. 51, and Galntz D. M., op. cit. p. 116.

39 http://www.stengerhistorica.com/History/WarArchive/Ritterkreuztraeger/Bauer.htm, http://www.ritterkreuz-traeger-1939-45.de/Infanterie/B/Bauer-Ludwig.htm According to the information in the above sources, until the end of the war four more tanks in which Bauer fought were hit.

40 Hermann C. H, op. cit., p. 121.

41 Hermann C. H, op. cit, p. 120.

42 Hermann C. H, op. cit., p. 122.

43 Hermann C. H, op. cit., p. 111.

44 Hermann C. H, op. cit., p. 123.

45 Hermann C. H, op. cit, p. 172.

46 Hermann C. H, op. cit, p. 124.

47 Nevenkin K, Fire Brigades: The Panzer Divisions 1943-1945, Winnipeg 2008, p. 266.

48 Hermann C. H, op. cit, p. 125.

49 Hermann C. H, op. cit, p. 172.

50 Ibidem.

51 Ibidem.

52 Hermann C H, op. cit., p. 130.

53 Hermann C H, op. cit., p. 127.

54 Tessin states that the order was issued May 1 1943. Tessin G., Verbände und Truppen...VI Band, Osnabrück 1972, p. 181.

55 Michalski H., Zapomniane wersje Panzera II, cz. II, Militaria XX wieku, Nr 3/2009, p. 78.

56 Nevenkin K, op. cit., p. 266.

57 Michalski H., op. cit., p. 75.

58 Michalski H., op. cit, p. 75.

59 Nevenkin K, op. cit., p. 266.

60 Michalski H., op. cit, p. 75

61 Stoves R, op. cit., p. 70.

62 According to Stoves, Pz.Rgt. 33 (Stab and I. Abteilung) received about 85 medium Pz.Kpfw. IV with a long barrel gun during that period; in comparison with the data cited by Jentz and Nevenkin, it seems to be a rather incredible number. Stoves, op. cit, p. 70.

63 Nevenkin K, op. cit., p. 281.

64 Hermann C. H., op. cit, p. 171.

65 At the time, heavy infantry cannons towed by means of motor traction were unofficially included in the unit.

66 Nevenkin K, op. cit., p. 278-281.

67 Including 50 mm anti-tank guns Pak 38, described by Neverkin, probably just like in the official German documents as mPak - mittlerePak - medium anti-tank cannon.

68 Nevenkin K, op. cit., p. 283-285.

69 Jentz T. L, Die deutsche..., op. cit., Band II , p. 79.

70 Nevenkin K, op. cit., p. 267.

71 Piekałkiewicz J., Operacja Cytadela, Janki k. Warszawy 2004, p. 107.

72 Newton S. H., Ulubiony dowódca Hitlera, Warszawa 2007 , p. 155-156.

73 Hermann C. H., op. cit, p. 130.

74 Newton S. H., op. cit., p. 162.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE CHART OF THE 9th PANZER DIVISION ON JULY 1943

Thus, the 9th Panzer Division was deployed on July 6. At 3:30, reinforced units of the XXXXVII Armoured Corps, over 600 combat vehicles strong, repeated the attack. On the left flank, the 6th Infantry Division led by General Grossmann, supported by the panzer grenadiers of the 18th Panzer Division and tanks from the 9th Panzer Division, was supposed to bypass Soborovka village, advancing toward hill 274 and Olkhovatka.75 At 5:40, Generaloberst Model placed a telephone call to Generalfeldmarschall von Kluge, commander of Army Group “Mitte”, revealing his plan of action. Generaloberst Model was convinced that the hills surrounding the townships of Ponyri, Olkhovatka, Kashary and Teploye would be captured before the end of the day. This achievement would allow the 9th Army to destroy the main lines of General Rokossovsky’s defences and continue an attack on Kursk. The problem with the plan was that during the breakthrough, the 2nd and 9th Panzer Division sustained such heavy losses that they would be unable to carry on the advance to surround the Soviet forces. Thus, the burden of the attack on Kursk would fall on the 4th Panzer Division. Generaloberst Model informed von Kluge that the assigned forces were too weak, so he asked if the 10th Panzer Grenadier Division (10. Pz.Gr.Div.) and the 12th Panzer Division could be deployed from the reserves of Army Group “Mitte”. 76

As the day progressed, the forces of the XXXXVII Armoured Corps, that is the 6th Infantry Division along with the 2nd and 9th Panzer Divisions, did not achieve any considerable success in penetrating the deeply arranged Soviet defence positions. In addition, the tactics of the attack had changed.77 Instead of infantry attacks supported by armour, the tanks and armoured guns spearheaded the advance. While the German tanks were able to gain ground in such a way, without infantry they could not hold the captured positions. “It explains the fact that the efforts aimed at breaking deeper into the Soviet lines made by the 2nd, 9th and the 20th Panzer Divisions were futile.”78 At about 15:30 hours, the army command received information that the 20th Panzer Division had captured Bobrik and was advancing towards Podolian. If the 2nd and the 9th Panzer Divisions were to immediately switch the aim of the attack from south to west, the manoeuvre would tie the forces of the 16th Tank Corps at a critical moment, so Generalleutnant von Kessel’s attack could accelerate.79 Unfortunately, the tactical objectives of the attack could not be altered at the level of 9th Army headquarters. By the time the information reached Generaloberst Model, at around 4 in the afternoon, it was too late to divert any armoured forces towards the west. At 16:30 hours, Model ordered a change in the 9th Army’s artillery support arrangement, to concentrate the barrage in the area of von Kessel’s attack. It turned out to be an unfortunate decision that led to a short lived chaos, as the 6thInfantry Division and the 9th Panzer Division lost their artillery support for some time.80

A group of 9th Panzer Division officers. The third from the left, an Oberst, was decorated with the Deutsches Kreuz in Gold. The second from the right has a rank of Hauptmann.

Meanwhile, the 9th Panzer Division conducted an attack on Ponyri township defended by the 307th Rifle Division under General Major Jenshin. The 9th Division encountered determined resistance from General Lieutenant Pukhov’s 13th Army, reinforced with mortar and anti-tank units.81 At about 18:30 hours, Model, most likely present at the front lines at the time, decided that the 4th Panzer Division led by General von Saucken, would not reinforce the attack conducted by the 9th Division. Instead, on July 7 it was to follow the 2nd Panzer Division.82

An Oberst from the 9th Panzer Division. The Deutsches Kreuz in Gold and the Winterschlacht im Osten ribbon are partially visible.

By the end of the day, the 9th Panzer Division launched an attack on the left wing of the Soviet 81st Rifle Division, which resulted in pushing the Russians back towards railroad station in Ponyri.83

As Model returned to his headquarters at about 21:30 hours, he received a detailed report of the combat actions performed throughout the day. He again rejected his staff proposal to dispatch the 4th Panzer Division behind the 9th in the direction of Olkhovatka. “He came up with the idea of consolidating the dispersed units of the 18th Panzer Division, so it could, along with the 9th Panzer Division, secure the key position at Snova, where the Soviet 16th Tank Corps concentrated its forces according to the aerial reconnaissance.”84

As proposed in this plan, the 9th Panzer Division would assume defensive positions, while the attack on Teploye would be conducted by the 2nd and the 4th Panzer Divisions. At the same time, the 86th and the 296th Infantry Divisions (86. and 296. Inf.Div.) were to capture Ponyri. “The last order of the day - July 6, was issued by General Model at 22:45, it reiterated the instructions for the 9th Army chief of staff von Elvefeldt to direct the 9th and the 18th Panzer Divisions to take defensive positions at Snova.” 85

An artillery Oberleut-nant decorated with the Eisernes Kreuz I klasse, the Verwundetena-bzeichen (Wound Badge) and Panzerkamp-fabzeichen (Tank Combat Badge). A self propelled Sd. Kfz. 165 Hummel gun is seen in the background