Chapter Fifty-Three

![]()

The Recapture of Constantinople

Between 1254 and 1261, the Latin Empire comes to an end, and the Byzantine Empire is restored

HALF A CENTURY BEFORE, Byzantium had splintered into four mini-kingdoms and faded from sight. For a little less than a millennium, Constantinople had been a pivot point of international politics; now, like Kiev, or Braga, or Krakow, it was of vast importance to its immediate neighbors, but little more.

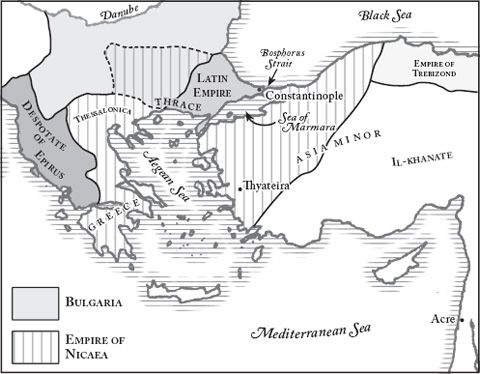

Constantinople now stood as the capital of the “Latin Empire,” a tiny and penniless realm. Immediately after the conquest of the city by the Fourth Crusade, the Latin Empire, under the Count of Flanders turned Emperor, had stretched from Constantinople into the south of Greece, across the Black Sea to encompass the coast of Asia Minor. But under the count’s nephew Baldwin II, who inherited the throne in 1228 at the age of eleven, the Latin Empire had shrunk. The Bulgarian empire, under the ambitious Ivan Asen, mounted constant attacks on its western border; the Empire of Nicaea, under the ruthless John Vatatzes, assaulted it from the east. Baldwin had few troops, and no money to hire mercenaries. A delegation of Franciscan and Dominican friars who visited the city in 1234 reported that city was “deprived of all protection,” the emperor a pauper: “All the paid knights departed. The ships of the Venetians, Pisans . . . and other nations were ready to leave, and some indeed had already left. When we saw that the land was abandoned, we feared danger because it was surrounded by enemies.”1

Baldwin spent much of his reign out of Constantinople, traveling from court to court in Europe and begging each Christian king to help him protect the city that had once been Christianity’s crown jewel in the east. Both Louis IX of France and Henry III of England made small contributions to the Latin treasury, but in its king’s absence Constantinople itself grew shabbier and hungrier. By 1254, Baldwin could claim to rule only the land right around Constantinople’s walls. He had already sold most of the city’s treasures and sacred relics: a fragment of the True Cross, the napkin that Saint Veronica had used to wash the face of Christ as he walked towards Golgotha, the lance that pierced Christ’s side on the cross, the Crown of Thorns itself. (Louis IX bought most of them and built a special chapel in Paris to house the collection.) He had borrowed so much money from the Venetian merchants that he had been forced to send his son Philip to Venice as a hostage pending repayment; he had torn the copper roofs from Constantinople’s domes and melted them down into coins.2

While the Latin Empire withered, the Empire of Nicaea grew. John Vatatzes, claiming to be the Byzantine emperor in exile, spent most of his thirty-three-year reign fighting: swallowing most of Constantinople’s land, seizing Thrace from Bulgaria and Thessalonica from the third of the mini-kingdoms, the Despotate of Epirus. (The fourth mini-kingdom, the Empire of Trebizond, never expanded very far away from the shoreline of the Black Sea.) By 1254, the Empire of Nicaea stretched from Asia Minor across to Greece and up north of the Aegean.

53.1 The Empire of Nicaea

In February of that year, the sixty-year-old John Vatatzes suffered a massive epileptic seizure in his bedchamber. He slowly recovered, but seizures continued to plague him. “The attacks began to occur altogether more frequently,” writes the historian George Akropolites, who lived at the Nicaean court. “He had a wasting away of the flesh and . . . no respite from the affliction.” In November, the emperor died; his son Theodore, aged thirty-three, became emperor.3

But Theodore II soon sickened with the same illness that had killed his father: “His entire body was reduced to a skeleton,” Akropolites says. He died before the end of his fourth year on the throne, leaving as heir his eight-year-old son John.4

John’s rule was promptly co-opted by the ambitious Michael Palaeologus, a well-regarded soldier and aristocrat who was also the great-grandson of the Byzantine emperor Alexius III. With the support of most of the Nicaeans (“They did not think it proper,” says Akropolites, “for the . . . empire, being so great, to be governed by a fruit-picking and dice-playing infant”), Michael first declared himself to be regent and then, in 1259, promoted himself to co-emperor as Michael VIII.5

From the moment he took the throne, Michael VIII intended to recover his great-grandfather’s city: “His every effort and whole aim was to rescue it from the hands of the Latins,” writes Akropolites. In the first two years of his reign, he prepared for the attack on Constantinople by making peace on his other borders; he concluded treaties with both Bulgaria and the nearby Il-khanate Mongols.6

He also equipped himself with a new alliance. The merchants of Genoa had just suffered a commercial catastrophe. In 1256, they had quarreled sharply with the Venetians over the ownership of a waterfront parcel of land in Acre, the last surviving fragment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Whoever controlled it could block rival ships from the harbor of Acre, and both of the maritime republics wanted this advantage. “The Christians began to make shameful and wretched war on each other,” says the contemporary chronicle known as the Rothelin Continuation, “both sides being equally aggressive.” The first major sea battle in the war, between a thirty-nine-ship Venetian fleet (reinforced by ships from friendly Pisa) and a fifty-galley Genoan navy, had ended with an embarrassing Genoan loss. Between 1257 and 1258, the conflict ballooned until all of Acre was at war:

And all that year there were at least sixty engines, every one of them throwing down onto the city of Acre, onto houses, towers and turrets, and they smashed and laid level with the ground every building they touched, for ten of these engines could deliver rocks weighing as much as 1500 pounds. . . . [N]early all the towers and strong houses in Acre were destroyed . . . [and] twenty thousand men died in this war on one side or the other. . . . The city of Acre was as utterly devastated by this war as if it had been destroyed in warfare between Christians and Saracens.7

The Genoans were the losers. By the end of 1258, they had been forced out of Acre completely; the old Genoese quarter in Acre was entirely pulled apart, and the Venetians and Pisans used the stones to rebuild their own trading posts.8

Now Genoa needed another trading base in the eastern Mediterranean. Carefully guarded negotiations between the Genoese statesman Guglielmo Boccanegra and the emperor Michael VIII went on during the winter of 1260, and ended in July of 1261 with the signing of a major treaty: the Treaty of Nymphaion, which promised the Genoese their own tax-free trading quarters in Constantinople, should they help the ambitious emperor to conquer it.9

The conquest itself was an anticlimax; Baldwin II was in no shape to resist, and the city was almost defenseless. As soon as the Treaty of Nymphaion was ratified, Michael sent a small detachment to Constantinople to issue a series of threats. The detachment discovered, to its surprise, that most of the remaining Latin army had been sent off to attack a Nicaean-held harbor island near the Bosphorus Strait. Under cover of thick dark, they climbed into the city, quickly overwhelmed the tiny remaining guard, and opened the gates. Baldwin himself, sleeping at the royal palace, woke up at the sounds of their shouts and managed to flee the city, leaving his crown behind him. The Latin Empire was no more.10

Michael VIII himself was camped to the north of Thyateira at the time. When news of the capture arrived at his camp, his sister woke him up by shaking him and saying, “Rise up, emperor, for Christ has conferred Constantinople upon you!” According to Akropolites, he answered, “How? I did not even send a worthy army against it.”11

Three weeks later, he arrived at the gates of Constantinople himself. He entered the city on August 14 as the first emperor of a restored Byzantium, and found a disastrous mess: “a plain of destruction, full of ruins and mounds.” The royal palace was so filthy and smoke-stained that it had to be scrubbed from top to bottom before he could take up residence in it.12

The Genoese, claiming their reward, now had a trade monopoly in Byzantium and held the premier position in the Mediterranean Sea. Baldwin II ended up in Italy, still claiming to be the emperor of the Latins.

Michael’s co-emperor, young John, remained behind in Nicaea. Michael VIII intended to rule the restored Byzantium on his own, founder of a new royal dynasty, without challenge. Four months later, he ordered the boy blinded and imprisoned in a castle on an island in the Sea of Marmara. The sentence was carried out on Christmas Day, 1261, the boy’s eleventh birthday.