11

The sour taste left by the failure of the Second Crusade undermined both the idea and practice of this method of Christian holy war, casting doubt on its motives and morality. Despite repeated and increasingly urgent appeals from Outremer, successive popes failed to inspire new general expeditions east despite employing the full armoury of religious rhetoric, spiritual inducements and diplomatic persuasion. Individual wealthy enthusiasts conducted armed pilgrimages east. Some possessed armed intent, such as the Holy Land addict Count Thierry of Flanders in 1157–8 and 1164–5 (on top of his visits in 1139 and 1148); others, such as Duke Henry the Lion of Saxony (1172), did not. Dynastic adventurers and opportunists could be lured east by the prospect of a lucrative or spectacular marriage, as in 1176, when William of Montferrat arrived to marry Sibyl, sister and heir to the leper King Baldwin IV. Yet after his death in 1177, even Sybil’s attractions failed to entice a bridegroom from the west. When, in 1175, Philip of Alsace, count of Flanders, planned to follow the family tradition with a prolonged stay in the Holy Land, he felt the need to consult the redoubtable intellectual, poetess, musician, mystic and fashionable spiritual sage Abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179). Philip asked whether God, with whom his correspondent claimed to be in direct contact, would approve. For once His message lacked clarity. Hildegard’s tepid endorsement only voiced approval of fighting the infidel in some imagined future, ‘if the time shall come’ when they threatened ‘the fountain of faith’.2 Such caution in crusading commitment touched Christendom’s other frontiers. Between 1149 and 1192, there were only three papal grants of Jerusalem privileges to conflicts with infidels in Iberia, and just one in the Baltic, in 1171. The Second Crusade cast a deep shadow.

Even when events conspired to offer some prospect of success, responses were negligible. In 1176, the Greek emperor, Manuel I, hoping to bolster his position in Asia Minor and Cilicia as well as his alliances in western Europe, announced his intention of leading a joint Greek and Latin expedition to the Holy Land. Despite Pope Alexander III’s vociferous urging, western support was dismal even before Manuel’s advancing army was defeated by the Seljuk Turks of Iconium at the battle of Myriokephalon on 17 September 1176. When a Greek fleet of 150 ships arrived at Acre the following year, squabbling and suspicions within the Jerusalem government led to the cancellation of the proposed attack on Egypt, shenanigans that confirmed western scepticism about the plight of Outremer and the honesty of its rulers.

By 1184, the political fabric of Christian rule in Syria and Palestine had become badly frayed, worn down by increased Muslim pressure, government financial difficulties, prolonged and desperate dynastic instability in Jerusalem and tensions between its rulers and those of Tripoli and Antioch. Yet the embassy led to the west by Patriarch Heraclius of Jerusalem in 1184–5 attracted mistrust, ridicule, indifference, self-interest and caution, verging on the dismissive. The patriarch met Pope Lucius III, the German emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, and Philip II of France before begging Henry II of England to lead a new crusade; he was offered money and empty promises. Only a handful of recruits volunteered. King Henry was recorded as remarking that the patriarch sought his ‘own advantage not ours’.3 Another witness saw only the jangling jewellery, aromatic perfumes and lavish display of wealth as the patriarch’s entourage passed through Paris, not the genuinely desperate plea for armed help.4 On the eve of the greatest defeat of western arms by a non-Christian army since the tenth century, at Hattin in Galilee on 4 July 1187, crusading appeared to have run its course, a model of holy war that, in the shape taken since 1095, had served its turn and lost its fierce popular resonances. The events of that summer’s day in the hills above Tiberias reignited them.

NUR AL-DIN, SALADIN AND THE MUSLIM REVIVAL

Writing in the early 1180s, the Jerusalem historian Archbishop William of Tyre, in a remarkable and justly famous passage, described how the strategic balance in the Near East had tilted decisively against the Franks. He attributed this deterioration to three developments: the sinfulness of contemporary Franks in contrast to their ancestors; the loss of the advantage that their religious zeal and military training gave the first crusaders over the then indolent and pacific locals; and the unification of Syria and Egypt:

In former times almost every city had its own ruler… not dependent on one another… who feared their own allies not less than the Christians [and] could not or would not readily unite to repulse the common danger or arm themselves for our destruction. But now… all the kingdoms adjacent to us have been brought under the power of one man. Within quite recent times, Zengi… first conquered many other kingdoms by force and then laid violent hands on Edessa… Then his son, Nur al-Din, drove the king of Damascus from his own land, more through the treachery of the latter’s subjects than by any real valour, seized that realm for himself, and added it to his paternal heritage. Still more recently, the same Nur al-Din, with the assiduous aid of Shirkuh, seized the ancient and wealthy kingdom of Egypt as his own… Thus… all the kingdoms round about us obey one ruler, they do the will of one man, and at this command alone, however reluctantly, they are ready, as a unit, to take up arms for our injury. Not one among them is free to indulge any inclination of his own or may with impunity disregard the commands of his overlord. This Saladin… a man of humble antecedents and lowly station, now holds under his control all these kingdoms, for fortune has smiled too graciously upon him. From Egypt and the countries adjacent to it, he draws an inestimable supply of the purest gold… Other provinces furnish him numberless companies of horsemen and fighters, men thirsty for gold, since it is an easy matter for those possessing a plenteous supply of this commodity to draw men to them.5

William’s analysis found confirmation from Muslim witnesses and events.

*

The Christian failure before Damascus in 1148 did not immediately lead to the unification of Syria. Nur al-Din of Aleppo (1117–74) was perceived by some in Damascus as a greater threat to their independence than the Franks. Although providing troops for Nur al-Din’s campaign, which culminated in the defeat and death of Prince Raymond of Antioch at Inab in June 1149, the Damascenes simultaneously agreed a new truce with Jerusalem which lasted almost until Nur al-Din’s annexation of Damascus in 1154. A joint Damascus/Jerusalem army besieged Bosra in the Hauran region in 1151, and Damascus regularly paid tribute to its Frankish neighbour, while continuing to appease Nur al-Din by allying with him in northern Syria. Only with the Frankish capture of Ascalon in 1153 did the majority of Damascus’s ruling elite decide that the Christians presented the greater threat. Even so, Nur al-Din’s occupation of Damascus in April 1154 only came after an economic blockade followed by an armed assault.6

The peaceful terms granted the rulers of Damascus showed that Nur al-Din was more accommodating than his brutal father Zengi. The jihad was integrated into the substance of his policies as he regularly demanded support for annual renewals of what he announced as holy war. In 1149, he advertised the significance of his victory at Inab by bathing in the Mediterranean. Religious propagandists travelled in his armies. Palestinian émigré poets in his entourage called for the reconquest of their homeland ‘until you see Jesus fleeing from Jerusalem’.7 In practice, as his critics pointed out, Nur al-Din spent most of his career engaged in subjugating other Muslims to his rule, annexing Damascus in 1154, Mosul in 1170 and contesting control of Egypt after 1163, and was willing to agree treaties with the invading Byzantine emperor in 1159 and the Jerusalemites in 1161. However, his inheritance of Aleppo, confining him to Syria rather than his father’s stamping ground of Iraq, imposed on Nur al-Din a more intense focus on his Frankish neighbours while at the same time depriving him of his father’s resources to effect territorial gains at their expense, a gap covered by jihad rhetoric and displays of private austerity and extreme spirituality. Nur al-Din’s image as the pious, just, puritanical mujahidwas displayed on inscriptions and coins and in the patronage of religious learning, schools, scholars and mosques. He cultivated a reputation as a just ruler and judge, a knowledgeable jurist and theologian, educated, literate, orthodox, although, in the words of an Iraqi panegyrist, Ibn al-Athir, ‘not a fanatic’.8 Nur al-Din’s piety apparently increased after serious illnesses, in 1157 and 1159, and a defeat by the Franks before Crac des Chevaliers in 1163, a pattern of penitential progress similar to that of another ruler who wore his faith on his sleeve a century later, Louis IX of France.

In 1161, Nur al-Din undertook the hajj and rebuilt the walls of Medina in the Hijaz, with Mecca the holiest cities in the Muslim world, gestures of obvious political as well as religious significance. Nominally, the Hijaz lay under the sovereignty of Egypt, although in practice ruled by local families claiming descent from the Prophet. Nur al-Din’s appearance and patronage announced a new power in Islam. Convenience and devotion entwined very effectively. The inscriptions on Nur al-Din’s elaborate minbar (or pulpit), built in Aleppo 1168–9, proclaimed his jihad credentials, not least in the declared intention to relocate it in the al-Aqsa mosque once the Holy City had been recaptured, a wish fulfilled by Saladin twenty years later. Such a pulpit, in which politicized polemic could be broadcast under the guise of the religious Friday sermon (the Khutba), represented a highly visible pledge of the unity between spiritual and political ambition, ideology and empire building. In consolidating an alliance with the newly strident and influential religious classes in law and administration, Nur al-Din hoped to reconcile political opponents to his dominance. He offered unity within Near Eastern Islam under the nominal authority of the Sunni caliph of Baghdad, whose express sanction for each conquest and annexation was deliberately sought. Not only in retrospect could Nur al-Din be seen as ‘the fighter of jihad, the one who defends against the enemies of [Allah’s] religion, the pillar of Islam and the Muslims, the dispenser of justice to those who are oppressed in the face of the oppressors’.9 His now more famous successor, Saladin, learnt the lesson and was careful to follow it.

Yet mid-twelfth-century Outremer did not seem about to capsize. While Muslim military incursions could still threaten disaster, in the kingdom of Jerusalem at least only the immediate frontier areas were regarded as presenting much risk to settlers. Despite the recriminations following the Second Crusade and a sharp and potentially damaging conflict (1149–52) culminating in open civil war (1152) between the young King Baldwin III and his mother, Queen Melisende, the Franks managed to stabilize the position of Antioch in 1150 and resume offensive operations. Nur al-Din’s attacks on Damascus were thwarted in the early 1150s. In moves to weaken Ascalon, the last remaining Palestinian port in Muslim hands, Gaza was rebuilt and given to the Templars in 1149–50. In January 1153, Baldwin III began to besiege Ascalon, which surrendered on 19 August, affording the king massive booty, a secure southern frontier and access to Egypt. By 1155, the alarmed but tottering Egyptian government began paying tribute to Jerusalem. By 1159, with Jerusalem’s ally Manuel I, the dominant figure in the eastern Mediterranean, exerting his overlordship in Antioch, arranging a treaty with Nur al-Din and contemplating war with Fatimid Egypt, William of Tyre’s analysis of a tightening noose would have appeared fantastic. However, the fate of Jerusalem was soon to be cast into hazard on the banks of the Nile.

The reorienting of Frankish defence strategy in the 1160s from northern Syria to Egypt marked an apparent reversal of tradition. From the reign of Baldwin I until the late 1150s, successive kings of Jerusalem had been drawn north to restore order and security in the wake of defeat, loss of leaders or internal political squabbling. The main military threats to Outremer’s survival since the 1110s had come from Aleppo, Mosul and the forces of the Jazira (i.e. Upper Mesopotamia) and Iraq. Left to itself, Damascus tended towards alliance with Jerusalem, while Fatimid Egypt had long abandoned active reconquest of Palestine. Baldwin II had reinforced this northern policy by marrying two of his four daughters respectively to Bohemund II of Antioch (d. 1130) and Raymond II of Tripoli (d. 1152). However, ties between Antioch and Jerusalem became strained by the aggressive behaviour of the new prince of Antioch, the glamorous Frenchman Reynald of Châtillon, who married Constance of Antioch in 1153. After scandalizing opinion by extorting money from Patriarch Aimery of Antioch through public torture, in 1156 Reynald broke the alliance with Byzantium by raiding Cyprus.10 Whether Reynald’s capture by Nur al-Din in 1161 and detention in Aleppo until 1176 strengthened or weakened the Frankish cause is unclear; it certainly removed a source of friction. Immediately, his capture involved Baldwin III in another round of political horse-trading between supporters of Constance and her son by her first husband, Raymond of Poitiers, Bohemund III. However, the city’s destiny was no longer his to decide since Manuel I’s personal assertion of his lordship over Antioch in 1159.11

Already talking of an assault on Egypt, Baldwin eagerly embraced a Byzantine alliance. In 1161 Manuel demonstrated his effective influence by installing Constance as ruler in Antioch after Reynald’s capture, rather than her son Bohemund III. Some historians have argued that the Jerusalem kings’ abandonment of northern Outremer represented a fatal error, allowing Nur al-Din’s authority in the region to grow unchecked. Yet it is hard to see how Baldwin or his successor, Amalric, could have continued to act as arbiters of Antioch without conflict with Byzantium. At the height of Latin Jerusalem’s power, Egypt must have seemed an almost irresistible source of ready wealth to compensate for declining revenues from the royal demesne. Nur al-Din’s involvement in Egypt was reluctant and not bound to prevail. War at a distance from his Syrian bases was costly. Egyptian politicians were antipathetic to Syrian interference. Any invasion from Syria had to be launched across the desert no man’s land between the Negev and northern Arabia, under the scrutiny of Frankish outposts and Bedouin spies. In such circumstances, Frankish engagement in the internal affairs of Egypt was neither capricious nor doomed; given the implosion of the Fatimid regime it was probably unavoidable.

If the reordering of alliances and policy by the Franks and their Muslim neighbours in the 1150s characterized the first phase of the process of encirclement described by William of Tyre, the second revolved around the battle for Egypt, which the Franks lost, providing Nur al-Din’s erstwhile Kurdish mercenary commander Saladin with the power base from which to create a new Near Eastern empire. During the 1150s, order within the Fatimid caliphate collapsed, with power and the viziership contested by a succession of provincial governors. Taking advantage of this, Baldwin III, fresh from conquering Ascalon, extracted tribute from one of the warring factions and toyed with an invasion, plans for which he discussed with Manuel I in 1159. In 1163, Egypt descended into anarchy, three viziers succeeding each other in a matter of months, the third of whom, the former chamberlain Dirgham, refusing payment of the Frankish tribute while his ousted predecessor Shawar sought help from Nur al-Din. The new king of Jerusalem, the fleshy but energetic Amalric, intervened to exclude Nur al-Din, gain booty and consolidate his rule at home.

Amalric’s first invasion, in September 1163, was only repulsed when the Egyptians breached the dykes in the Nile Delta near Bilbeis, about halfway upstream from the sea towards Cairo. The following year, Dirgham was killed and Shawar was restored by Nur al-Din’s Kurdish mercenary general Asad al-Din Shirkuh, only for the restored vizier to switch sides and call for Frankish help. Nur al-Din’s change of policy in 1164 from neutrality to reluctant engagement reflected a dependence on his Kurdish generals and their corps of mamluks, professional slave warriors whose loyalties rested with their commanders rather than to any nominal political overlord. Shirkuh regarded an Egyptian invasion as an opportunity to establish independent power of his own, the enterprise becoming a family business as he took with him his nephew as second-in-command, Yusuf Ibn Ayyub, better known as Salah al-Din or Saladin (1137–93). This ambition may have been detected by Shirkuh’s protégé Shawar, prompting his invitation to the Franks. Certainly, during this first invasion, Shirkuh took careful stock of Egyptian resources and the potential for the establishment of an Ayyubid kingdom.

The Frankish campaign in Egypt of August to October 1164, largely taken up with a siege of Bilbeis, ended when both Amalric and Shirkuh agreed to evacuate the country. Amalric’s apparent advantage in Egypt had been undermined by an attack on Antioch by Nur al-Din and his victory at Artah, about twenty miles east of the city, where Bohemund III of Antioch and Raymond III of Tripoli were both captured. However, Shirkuh, lacking reinforcements because of this war in northern Syria, could not maintain his position against a hostile local regime and its Frankish allies. Both protagonists left Egypt in 1164, their appetites for conquest far from satiated. By late 1166, Shirkuh’s plans for conquering Egypt had attracted the support of the caliph in Baghdad and acquiescence of Nur al-Din. This new invasion had been anticipated by Shawar, who once more called in the aid of the Franks, the two armies arriving more or less simultaneously, in January 1167. The fighting penetrated deep into Egypt beyond the Delta and south of Cairo, where, at al-Babayn in Middle Egypt, Amalric suffered a severe defeat at the hands of Shirkuh’s army in March. Despite this and the Franks’ failure to dislodge Saladin from Alexandria, the subsequent stalemate led to another evacuation of Egypt by both Franks and Syrians in August, leaving Shawar in power with a Frankish representative resident with troops in Cairo and an increase in the Jerusalem tribute. The scope and intensity of the war of 1167 suggest that Amalric was determined at least to establish a protectorate over Egypt, if only to prevent it falling into the hands of Nur al-Din or Shirkuh, while the latter’s intentions to annexe the country were now clear.

The crisis of the Egyptian wars came in the winter of 1168–9. Amalric attacked in October 1168, apparently intent on the conquest of Egypt, although he refused to wait for Byzantine naval assistance and lacked the support of the Templars. Amalric may have feared Shirkuh would conquer Egypt first. As it was, the Frankish advance forced the shifty but resilient Shawar into another precarious diplomatic somersault, accepting help from Shirkuh, whom he had double-crossed in 1164. After capturing and brutally sacking Bibleis, Amalric besieged Cairo. However, failing to provoke a decisive battle, the Franks were compelled to withdraw empty-handed in January 1169, leaving the field open for Shirkuh. On 18 January, Shawar, his nimble footwork at last failing, was assassinated by the Kurdish generals ostensibly on the orders of the teenaged Fatimid caliph al-Adid. Shirkuh succeeded to the viziership. However, on 22 March 1169, he succumbed to age, over three decades in the saddle, recent exertion and a longstanding heart condition exacerbated by over-indulgence, a taste for ‘rich meats’ and obesity (in contrast to his porcine rival, King Amalric, whose weight represented a cruel reward for moderation in food and drink).12 Despite the reservations of more senior Turkish commanders in the army, Saladin replaced him.

Initially, Saladin’s tenure appeared insecure, the fifth vizier in six years. His personal military entourage was outnumbered by the Turkish contingents from Syria, many of whom returned north with their disgruntled emirs after his accession. His remaining forces, a few thousand, were dwarfed by the Fatimid armies, especially by the 30,000 black infantry troops, the Sudan. His political position appeared hopelessly anomalous: an orthodox Sunni Kurd, nominally subject to a foreign overlord, sustained by a dwindling Turkish army from Syria, attempting to rule a large, unsubdued and populous country in the name of a Shi’ite caliph. Yet within a year he had destroyed the Black Sudan and repulsed a dangerous assault by land and sea by a combined Frankish-Greek amphibious force at Damietta. With the failure of this, Amalric’s fifth invasion of Egypt in six years, and despite an attack on Alexandria by a Sicilian fleet in 1174 and the planned Byzantine naval assault of 1177, the Franks’ gamble, legitimate in conception, skilfully funded by an unscrupulous monarch but bungled in execution and myopic in long-term strategic assessment, had failed, handing a major advantage to their enemies.

In 1170, Saladin went on to the offensive, capturing Gaza and Aila on the Red Sea from the Franks, harrying the remnants of the Sudan and extending his hold on Arabia and Yemen. Although further policing operations in Egypt and Yemen were necessary, Saladin’s power was secured, not least by his careful creation of his own military corps, or askar, the Salahiyya, and grants of revenues (iqta) to his followers, especially his immediate family. His father, Naim al-Din Ayyub (d. 1173), received huge income from the Delta and its ports. In concert with Nur al-Din’s policy of overt religious orthodoxy, in September 1171, on the death of the Fatimid caliph al-Adid, Saladin had the name of the Sunni Abbasid caliph of Baghdad al-Mustadi (1170–80) inserted into Friday prayers.13After 202 years, the Fatimid caliphate of Cairo was at an end, an achievement of religious unity for which Saladin, the reluctant executor of Nur al-Din’s wishes, subsequently took credit. While the new sultan of Egypt consolidated control of the southern periphery of his empire, Nur al-Din began to prepare against this upstart. Twice, in 1171 and 1173, Saladin had withdrawn from joint expeditions against the Franks in Transjordan. Open war seemed imminent when, ‘in the midst of preparations’ to invade Egypt, Nur al-Din died suddenly of a heart attack in Damascus on 15 May 1174.14 On 11 July King Amalric, after a prolonged fever, died in Jerusalem aged thirty-eight. By the end of October, Saladin had entered Damascus. The third, final stage of William of Tyre’s encirclement was about to begin.

The career of al-Malik al-Nasir Salah al-Dunya wa’l-Din Abu’l Muzaffar Yusuf Ibn Ayyub Ibn Shadi al-Kurdi, known to westerners during his lifetime and ever since as Saladin, epitomized the fluidity and the opportunities of Near Eastern politics in the twelfth century.15 Born the son of a displaced Kurdish mercenary in the service of Zengi of Mosul, he died the creator and ruler of an empire that embraced Iraq, Syria, Arabia and Egypt, the effective overlord of the Fertile Crescent, a successful dynast whose arriviste family became the political masters of the Near East for over half a century. His legend, carefully fashioned by members of his entourage after his death, received unlikely promotion by Christian authors in the west. Saladin’s reputation as a noble adversary of honour, chivalry, clemency and justice, invented in the immediate aftermath of the Third Crusade (1188–92), became a staple image of crusading from the vernacular cycles of crusade epics and romances of the thirteenth century into the pulp history of the twenty-first. Such was the admiration he inspired in western commentators that they paid him the ultimate compliment of imagining he had received the belt of knighthood from a Frankish knight, identified by a writer during the Palestine war of 1191–2 as Humphrey II of Toron, constable of Jerusalem (d. 1179).16 Such fictions of Saladin’s chivalry were enshrined in verse and the visual arts across western Europe; in the early 1250s, for example, he appeared jousting with Richard I in wall paintings and tiles decorating new apartments of Richard’s nephew, King Henry III of England.17

What struck western contemporaries most was Saladin’s generosity, a quality admired equally by his contemporaries the German poet Walter von der Vogelweide (c.1170–1230) and the French, possibly Norman versifier of the story of the Third Crusade, Ambroise, who remarked within a few years of Saladin’s death that ‘in the world there was no court where he enjoyed not good report’.18 Ironically, such admiration for the stereotype ‘good pagan’, as Saladin appears in Dante’s Inferno beside Hector, Aeneas and Julius Caesar, was not universally shared by thirteenth-century Arabic writers. Saladin and his family had made too many enemies. The Iraqi Izz al-Din Ibn al-Athir’s extensive history of the Muslim world, while recognizing Saladin’s achievements, questioned the image and propaganda. The famous magnanimity at Jerusalem in 1187, when Saladin allowed the helpless Franks safe conduct out of the city, was tempered by Ibn al-Athir’s claim that the sultan’s initial instinct was to exact full revenge for the Franks’ atrocities of 1099. According to Ibn al-Athir, Nur al-Din detected in Saladin a reluctance to fight the Franks ‘as he should’, his own emirs urging him to engage the Franks in battle at Hattin in 1187: ‘because in the East people are cursing us, saying that we no longer fight the infidels but have begun to fight Muslims instead’.19 Although his fame hardly dimmed in the west, bizarrely finding new life during and after the Enlightenment as a rational and civilized figure in juxtaposition to credulous barbaric crusaders, from the fourteenth to the late nineteenth century Saladin’s repute in Islamic and Near Eastern memory paled beside that of Nur al-Din and the great Mamluk sultan of Egypt Baibars (1260–77).

The reflections of Saladin’s emirs in Ibn al-Athir’s account of the Hattin campaign go to the heart of Saladin’s politics and reputation. Between 1174 and 1186, Saladin completed the encirclement of Outremer observed by William of Tyre, who probably died in 1186. Through a mixture of force and diplomacy, Saladin gradually asserted his control over Syria and the Jazira, beginning with Damascus in 1174. He was not greeted with unalloyed enthusiasm. His control over most of Syria was hard won between 1174 and 1176. Aleppo was annexed only in 1183 and Mosul in 1186. Attacks on the Franks were sporadic and rare; success modest. Defeated in a skirmish in southern Palestine in 1177 (known to the Franks as the battle of Montgisard) and at Forbelet in Galilee in 1182, he captured Jacob’s Ford in northern Galilee in 1179 and the waterless island of Ruad in 1180. In 1182 Beirut withstood a sea-borne attack, and a large prospective invasion following the taking of Aleppo in 1183 stalled when the Jerusalem army refused battle. In practical terms, war with the Franks appeared secondary to securing Nur al-Din’s inheritance. For most of the period 1174–87 truces prevailed, the final assault on Outremer only coming when other opportunities for expansion had been exhausted. Saladin’s power depended on his ability to reward followers and allies with revenues and lucrative offices. Any slackening of this rich stream of patronage threatened his authority over his mamluks, his own family members placed in command of his conquests and those non-Ayyubids, including some reconciled Zengid princes, who expected reward for subservience. Consequently, territorial expansion provided both the object and the sustenance for Saladin’s policies.

Nur al-Din’s legacy also included championing orthodox religion and the jihad. Saladin cultivated these with determination, whether, as his panegyrists insisted, out of private conviction, or from public convenience, or both, is not now possible to judge. As a parvenu Kurd, seeking to rule a largely Turkish aristocratic military elite that had once been his employer, Saladin needed the legitimacy the jihad could bestow. Already before Nur al-Din’s death, he could boast the deposition of the heretic Fatimids and at every stage of his career he presented himself in the image of a Koranic leader. Prepared to crucify Islamic heretics, Saladin’s public orthodoxy attracted the hostile attentions of the Assassins, the suicide killers of their day, until, after surviving two attempts on his life, Saladin arrived at a peaceful accommodation with their leader in the Lebanon, Rashid al-Din Sinan (1169–93), the Franks’ ‘Old Man of the Mountains’.20 Public displays of religious devotion and personal piety featured prominently in Saladin’s style as ruler, conveying important political messages. The ritual cleansing of the Dome of the Rock and its surroundings performed in person with other members of his family during the physical de-Christianizing of Jerusalem in 1187 demonstrated the status of the Ayyubids as the new protectors as well as rulers of Islam.21

Such propagandist posing occupied a central place in the biographical eulogies by Saladin’s secretary Imad al-Din al-Isfahani and his friend and official Baha’ al-Din Ibn Shaddad. It also played a pivotal role in his actual political behaviour. To emphasize his loyalty to the jihad, he placed Nur al-Din’s minbar from Aleppo in the al-Aqsa mosque as his predecessor had intended. Also following Nur al-Din’s example, he paid especial attention to relations with the caliphs of Baghdad, whose formal recognition could lend a veneer of respectability to his conquests. In 1175 he won investiture by Caliph al-Mustadi of Egypt, Yemen, future conquests and Syria except for Aleppo, although opposition from the last great Abbasid caliph, al-Nasir (1180–1225), thwarted his designs on Mosul in 1182. Saladin peppered the court in Baghdad with flattering correspondence implying he acted as the caliph’s servant, not least the newsletter he despatched to al-Nasir a few days after the victory over the Franks at Hattin in July 1187, which dripped formal obeisance to the caliph’s superior authority.22 Religious duty refined political imperative. Ibn Shaddad recorded a conversation with Saladin on the coast road between Ascalon and Acre one stormy day in 1189 during which the sultan declared his eagerness, once all the Franks had finally been expelled from Outremer, ‘to set sail to their islands to pursue them there until there no longer remain on the face of the earth any who deny God’.23 Wrapped in this rhetorical hyperbole lay the imperative of his system of patronage, loyalty and discipline; each conquest had to be followed by another.

The problem for the sultan’s apologists was that before 1187 Saladin’s military energies were primarily directed against fellow Muslims. For all his glamour as a conqueror of Egypt, Syria and Palestine, Saladin proved a cautious, at times nervous, field commander, better at political intrigue, diplomacy and military administration than the tactics of battle or the strategy of campaign. His successes at Damascus (1154), Aleppo (1183) and Mosul (1186) came through the application of political coercion and diplomacy, not brutal assault. Christian armies defeated him at Montgisard in 1177, Forbelet in 1182, Arsuf in 1191 and Jaffa in 1192. Indecision cost him Tyre and Antioch in 1187–8. His failure to snuff out the paltry Christian army in the early stages of the siege of Acre in 1189 remains hard to explain. Diplomacy rather than combat allowed him to withstand the Third Crusade, as it had ensured his alliance with the caliph, neutralized the Seljuks of Asia Minor and sown division in the kingdom of Jerusalem with his treaty with Raymond III of Tripoli in 1185–7. This preference for political arts cannot be ascribed to a lack of military experience or personal squeamishness; the massacres of the Sudan in 1169 and the butchery of the Templars and Hospitallers after Hattin give that the lie. What distinguished Saladin, as William of Tyre sensed, was a highly developed opportunism sustained by an unsentimental appreciation of how to achieve ends through blandishment rather than force, coupled with considerable skill at managing administrative systems and people. Even so, for all his qualities as a politician, Saladin’s triumph over the Franks was eased by debilitating forces within Outremer for which he could claim no responsibility.

THE DECLINE OF THE KINGDOM OF JERUSALEM 1174–87

From the third quarter of the twelfth century, political society in Outremer, in western eyes prosperous, extravagant, self-absorbed, fractious and corrupt, suffered a cumulative crisis only partly the fault of its leaders. In the north, the principality of Antioch had been reduced by Nur al-Din to the coastal strip west of the Orontes. In the kingdom of Jerusalem, as has been seen, political stability was increasingly frayed by the rapid succession as monarchs of a possible bigamist (Amalric), a leper (Baldwin IV), a child (Baldwin V) and a woman (Sybil) with an unpopular arriviste husband (Guy). Protected by a series of truces with Saladin, appearances of wealth and power, noticed by Christian and Muslim travellers in the 1170s and 1180s, concealed and encouraged self-indulgent factional politicking. From 1174 to 1186 constant jockeying for control of the regency, the ill and infant kings or royal patronage diverted attention from the more intractable problems of defence and finance.

Although revenues from commerce, especially from the port of Acre, were buoyant, the incomes of the king and his greater barons seemed increasingly inadequate to meet expenditure, especially on defence. Across the kingdom there was a move towards castles and fiefs within lordships being acquired by wealthy ecclesiastical corporations, such as the Canons of the Holy Sepulchre and, especially, the military orders of the Templars and Hospitallers. These could draw on wide networks of resources from Outremer and estates in western Europe. In the lordship of Caesarea, by 1187, perhaps as much as 55 per cent of landed property was in religious hands, the bulk of it owned by the military orders. In the frontier lordship of Galilee, all the major castles except Tiberias itself seem to have been in the hands of the Templars or Hospitallers by 1168.24 If secular lordships were withering, sustained by money fiefs rather than land, the crown retained considerable powers of patronage and wide sources of revenue, including custom and harbour dues, taxes on Muslims and pilgrims, profits from minting coin as well as from the royal demesne, including the farming-out of proceeds from local industries, such as sugar production. However, with no new lands being conquered, the demands of patronage denied the crown much scope for increasing its ordinary income. The 1167 invasion of Egypt required a special 10 per cent income tax on those who declined to join the expedition, agreed at an assembly at Nablus that apparently included representatives of ‘the people’ as well as the clerical and lay magnates.25 In 1183, a comprehensive survey of landholdings in the kingdom was conducted (a census) to provide a basis for a new assessment of military obligation. According to the well-informed William of Tyre, chancellor of the kingdom at the time, faced with the prospect of greater pressure from Saladin, ‘the king and the barons were reduced to such a desperate state of need that their revenues were entirely insufficient to provide for the necessary outlay’, leading them to agree to a new national war tax on all inhabitants, regardless of language, race, religion or sex. This process of land census followed by fiscal imposition is reminiscent of the Domesday Survey of 1086 in England. The nature of the tax, 2 per cent on income above 100 besants as well as 1 per cent on land worth more than 100 besants, with a graded hearth tax below that, echoed that of 1166 and in part presaged the Saladin Tithe of 1188 and thirteenth-century English parliamentary taxation in the west, not least in the explicit element of consent described by William of Tyre: ‘by the common consent of all the nobles, both secular and ecclesiastical, and by the assent of the people of the kingdom of Jerusalem… for the common good of the realm’.26 This was parliamentary language.

The underlying problems were not just financial. Despite the de facto overlordship of the king of Jerusalem, Outremer’s disjointed authority (Antioch, Tripoli and Jerusalem) militated against coherent strategic planning along the whole of the Christian frontier, although the rise of the military orders may have acted as a compensating balance to this fissiparous tendency. More damaging in the circumstances of the 1170s and 1180s was the heavy political, administrative and military reliance on the person of the ruler. The severely disabled leper King Baldwin IV was forced to preside in person over his administration and meetings of his council and to attend campaigns and battles even if he had to be strapped to his horse or carried in a litter. Whenever he tried to relinquish the increasingly intolerable burden for a partly paralysed, nearly blind invalid, whose physical disintegration caused him to shun company, he found he could not. William of Tyre’s heroic Baldwin was trapped in a political system, fragile in its narrowness, vulnerable to internal faction as to external attack.27

In contrast with the system of consultative assemblies on display in 1167 and 1183, this lack of executive institutional sophistication matched limited military resources. An incomplete list of obligations from c.1180 indicated 675 knights owing to the king, which might represent about 700 in full, with service from churches, monasteries and towns, in the form of sergeants, potentially adding c.5,000 troops, as well as the military orders, perhaps another 700 knights and, crucially, bodies of mercenaries, such as Turcopoles or Bedouin.28 In theory, to these more or less trained troops could be added the levée en masse in times of emergency. Yet, as the campaign of 1187 revealed, raising the full complement of armed forces left vital castles and cities defenceless; the castle of Le Fève in Galilee was emptied of defenders during the preliminaries to Hattin and the city of Jerusalem contained just two knights by the time Saladin began his siege in October 1187.29 Any supplement of mercenaries required funds, which the kings and barons seemed increasingly to lack, in 1187 having to plunder the treasure deposited in Jerusalem by Henry II of England in expiation for his involvement in the murder of Thomas Becket in 1170. Yet it was lack of manpower not cash that posed the greatest threat. Small wonder that the refusal of western rulers to commit troops to Outremer in 1184–5 left Patriarch Heraclius ‘much distressed’.30

Despite containing Muslim pressure, increasing political dysfunction corroded Jerusalem’s unity of policy and purpose. The origins of the problems can be traced to the reign of Amalric. In 1163, the new king was forced at repudiate his wife, Agnes of Courtenay, sister of Joscelin III of Courtenay, heir to the lost county of Edessa. The stated grounds for the divorce were consanguinity, but some have argued that when Amalric and Agnes married in 1157, she was already married to Hugh of Ibelin, to whom she returned as wife after her separation from Amalric.31 Whatever the truth of the royal marriage, its annulment revealed a ruling elite that calculated personal and immediate gain above destabilizing the monarchy on which their own power depended. Behind opposition to Amalric may have lurked the decline in baronial wealth and authority within their own lordships, making royal patronage even more fiercely contested, raising anxieties lest Agnes, as queen, would seek to find lordships and fiefs for her landless brother and other dispossessed Edessans. The legacy of the civil war of 1152, when Amalric sided with his mother Queen Melisende against Baldwin III, may have fuelled suspicion, as well as personal dislike. Amalric’s taciturn dourness, absence of charm and lack of affability was noted even by his friend and protégé William of Tyre. Apparently, the new king was regularly heckled and insulted both in public and private, taunts he affected to ignore. More seriously, he was accused of failing to control his ministers and officials, although this may simply refer to the unpopularity of Amalric’s favourite and, from 1167, seneschal (i.e. head of the civil administration), Miles of Plancy.32 Some may have wished to annul Amalric’s marriage to free him to conclude a diplomatically more advantageous match, much in the fashion of Baldwin I’s marriage to Adelisa of Sicily half a century earlier (which was certainly bigamous). In 1167 Amalric did in fact marry Maria Comnena, great-niece of Manuel I.

Although the politics of Amalric’s reign revolved around the Egyptian war, later battle-lines began to coalesce around Amalric’s intimates and his new wife, Maria and, after 1172, her daughter Isabella, as opposed to his first wife, Agnes, and her children, Baldwin and Sybil. Even though Agnes had little or no contact with her children after her divorce from the king, the reversionary interest that surrounded them pointed to her role as future queen-mother. Agnes also established extensive contacts within Jerusalem first by her marriage (or remarriage) to Hugh of Ibelin, lord of Ramla, linking her to the fastest-rising local seigneurial family, then, after Hugh’s death c.1169, her taking as her fourth husband (her first had died as long ago as 1149) Reynald Grenier, the ugly, intellectual lord of Sidon, noted for his command of Arabic language and literature.33 Such affiliations were lent increased significance by an oddity of Amalric’s reign, the fortuitous absence from the political scene of three leading lords who later dominated Jerusalem politics. Reynald of Châtillon, erstwhile prince of Antioch, had been in captivity in Aleppo since 1161; Joscelin III of Courtenay followed him into Aleppan captivity in 1164, as did Raymond III of Tripoli. The release of all three between 1174 and 1176, and their subsequent elevation to leading positions within the kingdom of Jerusalem, transformed the politics of the reign of Amalric’s leper son.

In monarchies where an element of hereditary succession, especially primogeniture, had become established, minorities were inevitable, paradoxical destabilizing tributes to greater dynastic stability, the rights of the genetic heir overcoming the practical need for leadership. On Amalric’s sudden death in July 1174, after a debate probably focusing on the already worrying signs of the thirteen-year-old heir-presumptive’s illness balanced by the lack of obvious, uncontentious or available alternatives, the High Court agreed to the accession of Prince Baldwin. His elder sister Sybil was an unmarried convent girl; his young half-sister Isabella was only two. A regency would only have to last until Baldwin was fifteen, the Jerusalem age of majority. If the young king’s leprosy had been diagnosed, almost certainly he would not have been chosen.34 Yet doubts either about the prospects for his survival or his ability to have children may have already surfaced. The marriage of his sister Sybil, with its direct implication for the succession, had been discussed a few years earlier. Baldwin’s accession and the rapid realization that he was a leper and would be short-lived and childless, meant that his reign was dominated by reversionary factions defined, at least in part, by the competing claims of the king’s sister and half-sister, each backed by their mothers, Agnes of Courtenay and Maria Comnena.

Partly as a result of the way the highly partisan William of Tyre described events, the feuding in Jerusalem after 1174 has often been characterized as between the old, indigenous baronage, cautious, shrewd, realistic, and a court coterie of grasping Courtenays, Agnes and her brother Joscelin, titular count of Edessa and seneschal of the kingdom, allied to newcomers from the west, rash, ignorant of local conditions and dangers, provocative towards Saladin, selfish and greedy in their pursuit of power and conduct of government. The evidence fails to sustain this interpretation.35 Under Baldwin IV the fiercest factional competition revolved around control of the machinery of government, under the king or, when he was incapacitated, through a regency, and over the succession. Separately, contrasting approaches to strategy in dealing with Saladin emerged. Some, such as Reynald of Châtillon, after his release from captivity in 1176 established as lord of Hebron and Oultrejordain, pursued an aggressive policy to distract Saladin from his conquest of Muslim Syria. Others, such as Raymond of Tripoli, advocated serial truces as a means of containing the sultan. Similarly, the importance given to diplomatic alliances with Byzantium and/or western powers provoked disagreement, not least, perhaps, after Amalric’s possible acknowledgement of Manuel I as his overlord during a visit to Constantinople in 1171.

Much antagonism sprang from personal rivalries nurtured in the hothouse of Outremer’s small, closed aristocracy, the complexities of which, while hard to follow, expose layers of intense suspicion and rivalry. Reynald of Châtillon’s wife, Stephanie of Milly, heiress of Oultrejordain, may have blamed the murder of her previous husband, Miles of Plancy, in 1174 on Raymond of Tripoli. A broken promise of a wealthy Tripolitanian heiress in the 1170s may have lain at the root of the hostility shown in the 1180s towards Count Raymond by Gerard of Ridefort, Master of the Temple (1185–9). William of Tyre’s own perspective may have been coloured by having been appointed archbishop of Tyre and chancellor of the kingdom in 1175 by Raymond of Tripoli during the regency of 1174–6 and being passed over for the patriarchate of Jerusalem in 1180, possibly at the behest of Agnes of Courtenay.36 One notably hostile source towards the opponents of Raymond of Tripoli in the 1180s may reflect the views of the count’s allies, the Ibelins.37They had been allied to Agnes of Courtenay at the start of Baldwin IV’s reign but after the marriage of Balian of Ibelin to Dowager Queen Maria Comnena in 1177 supported the interests of Princess Isabella against her elder half-sister Sybil. In 1186, on the accession to the throne of Sybil and her husband, Guy of Lusignan, Baldwin of Ibelin quit the kingdom in disgust. There were also those whose loyalties rested not with any fixed party but with their own self-interest or with the monarch. Warriors such as Reynald of Châtillon and the constable, Humphrey II of Toron (d. 1179), remained conspicuously loyal to the king whatever their personal feelings towards whichever faction was dominant at court. Criticism of Reynald’s bellicose policy towards Saladin could with as much justice be directed at Baldwin IV, whose periods of rule showed him eager to take the battle to the enemy.

The evolution of the factions demonstrated fluid self-interest. After Amalric’s death most of the local baronage, including Agnes of Courtenay and Raymond of Tripoli, opposed the power of the unpopular seneschal Miles of Plancy. Yet after his assassination in October 1174, possibly organized by political rivals exploiting an old baronial feud, and Raymond’s subsequent regency (1174–6), political allegiances shifted. When Raymond surrendered the regency on Baldwin coming of age, 15 July 1176, the king appointed as seneschal and chief minister his recently released uncle, Joscelin of Courtenay, and immediately reversed Raymond’s policy of truce with Saladin, personally conducting two minor campaigns across the frontier in the same year. The arrival of William of Montferrat to marry Princess Sibyl in 1176 further alienated Raymond and his supporters. In 1177, on the sudden death of William of Montferrat in June, Baldwin, who was seriously ill, appointed Reynald of Châtillon as his regent, a snub less to the indigenous nobility or to Raymond personally than to the count’s supine foreign policy. With Reynald Baldwin won the famous victory at Montgisard in southern Palestine on 25 November 1177, when a potentially fatal Muslim invasion was caught off-guard and routed by a much smaller Frankish army. Yet earlier in the year a far greater prize, the prospect of a new amphibious attack on Egypt by the newly arrived Philip of Flanders together with a Byzantine fleet and a Jerusalem army, came to nothing, in part because of Philip’s ambitions laced with over-fastidious diplomacy, but in part because of the failure of the Outremer nobility to speak or act as one.38

For all his courage and determination, the longer Baldwin IV lived, the less able he was to rule. Nobody appreciated this more than the king despite his consistent political and public composure in the face of unimaginable physical and private agony. In 1177 he may have offered to abdicate in favour of his new brother-in-law, William of Montferrat. In 1178, after the birth of her son, another Baldwin, the king began associating Princess Sybil in official documents.39 Her remarriage became a central issue of Jerusalem politics, taking precedence over the threat from Saladin. In 1180, Raymond III of Tripoli, since his marriage to Eschiva of Bures lord of Galilee and thus one of the most powerful magnates in the kingdom, with his cousin Bohemund III of Antioch attempted a military coup d’état to secure a marriage for Sybil more favourable to their interests than the foreigners paraded as candidates over the previous three years. They invaded the kingdom and, it seemed to Baldwin IV, threatened his deposition as well as the removal of the Courtenays from power. The insurgents’ choice for Sybil’s hand appears to have been Baldwin of Ibelin, a former suitor rejected in 1178, brother-in-law to the Queen Dowager Maria. The king’s response was hurriedly to agree to the marriage of his sister to a Poitevin nobleman, Guy of Lusignan, recently arrived in Outremer from the west, brother of a close associate of the Courtenays, some alleged Agnes’s lover, Aimery of Lusignan. As a sign of how tangled the personal and political affiliations had become in Outremer, Aimery, later (1181/2) constable and, later still, king of Jerusalem as well as ruler of Cyprus (1194–1205, king from 1197), had, on arrival in the east in 1174, married Baldwin of Ibelin’s daughter. Sybil’s hasty marriage to Guy spiked the plans of Raymond and Bohemund and provided Baldwin with an active male successor and available regent. As a vassal of Baldwin’s Angevin first cousin Henry II of England, Guy could also claim links to a major western power. However, to supporters of Raymond of Tripoli, opponents of the Courtenays and those blessed with the perception of hindsight, the whole episode reeked of court intrigue. Within two years, Sybil’s party had secured their authority and placed their adherents in key positions. Guy became the premier baron in the land as count of Jaffa and Ascalon, King Amalric’s old county. With Sybil, he began to be associated in royal diplomas as the heir apparent.40 In 1180 the patriarchate of Jerusalem went to another supposed lover of Agnes of Courtenay, Archbishop Heraclius of Caesarea, a resourceful if possibly sybaritic politician and diplomat. However, he had pipped the historians’ historian William of Tyre to the job. The same year, the potentially troublesome Princess Isabella was removed from her mother and betrothed to Humphrey III of Toron, stepson of Reynald of Châtillon, the regime’s chief field commander. By 1182, Aimery of Lusignan had been appointed constable, the same year that the failure of another attempted coup by Raymond of Tripoli forced him to be reconciled with the government.

Guy of Lusignan’s emergence as Baldwin’s probable heir did not prevent resistance to Saladin, who was now stretched between defence of his northern frontier against the Seljuks of Asia Minor, designs on Mosul and Aleppo, ambitions in Outremer and protection of the desert-land routes between Syria and Egypt. A two-year truce, 1180–82, ended with Saladin’s defeat at Le Forbelet in Galilee in July 1182, failure to take Beirut and the consolidation of Frankish control of the eastern bank of the river Yarmuk. To the south, Reynald of Châtillon disrupted not only Saladin’s material power but also the ideology of his political authority with a foray into the Arabian desert in 1181 and by sponsoring a prolonged raid along the Red Sea coast in 1182–3 that disrupted the annualhaj. Saladin acknowledged the outrage by having two Frankish captives from the raiding fleet taken to Mecca itself where, at Mina outside the city, in front of crowds of pilgrims, they had their throats cut. Although of no lasting strategic impact, these raids alarmed the Muslim world, challenging Saladin’s pose as the Champion and Defender of Islam. No Christian fleet had sailed the Red Sea since the seventh century; the unfortunate captives were perhaps the first Christians to have set foot in Mecca since its capture by Muhammed in 629.41

Reynald’s southern campaigns proved the first kingdom of Jerusalem’s final fling. In June 1183 Saladin finally occupied Aleppo. In August he turned his attention southwards to Jerusalem. The kingdom mobilized a large army, according to William of Tyre 1,300 cavalry and 15,000 infantry, numbers swelled by the census earlier in the year and mercenaries paid by the subsequent tax.42 The Christian army gathered at Sephoria in Galilee. The great magnates were attending the king at Nazareth when Baldwin fell seriously ill and was thought to be dying. He summoned the High Court to his sickbed and appointed Guy of Lusignan as regent. The regency was to be permanent, Baldwin retaining only the title of king, ownership of the Holy City itself and an annual pension of 10,000 gold pieces with a promise from Guy not to alienate royal treasure or lands during the king’s lifetime.

Apart from initial skirmishes, the Galilee campaign in September and October 1183 saw no military engagement. The Christian army shadowed Saladin’s force as it manoeuvred in southern Galilee, but refused to confront the invaders, despite Muslim raids on Mt Tabor’s monasteries and threats to Nazareth. Unable to bring the Franks to battle and lacking the numerical superiority to launch an assault on their camp, Saladin withdrew to Damascus in early October. Tactically, the Franks had prevailed with the minimum of losses. However, many in the Jerusalem high command thought that strategically they had missed an opportunity to destroy Saladin’s army. Aggression had paid dividends in 1177 at Montgisard and in 1182 at Le Forbelet with far smaller forces at the Franks’ disposal. Moreover, it was the duty of Christian knights to protect holy sites such as Mt Tabor from Muslim desecration. In the eyes of some observers, admittedly hostile to Guy, the management of the campaign, despite its satisfactory if not triumphant outcome, left much to be desired. Some leaders had refused to cooperate with Guy. Tactical inertia, partly the result of this inability to command confidence and unity, had been matched by inadequate provisioning of food. Many saw Guy’s apparently supine performance as proof of his inability to lead. Four years later, memory of this perception proved fatal as the Franks, led once more by Guy, rejected the caution of 1183 only to be annihilated at the Horns of Hattin.

Guy’s perceived shortcomings as a war leader were immediately compounded by his refusal to accede to King Baldwin’s request to exchange Jerusalem for Tyre. Support for the regent ebbed. In November 1183 Saladin began a siege of Kerak in Oultrejordain while the castle was hosting the marriage between Princess Isabella and Humphrey IV of Toron. Facing this fresh crisis, Baldwin engineered a palace revolution. Guy was stripped of the regency and a new succession was arranged excluding him, signalled by the coronation of his stepson, the five-year-old Baldwin, son of Sybil and her first husband William of Monteferrat. To prevent Guy’s return to power, moves were begun to annul his marriage to Sybil. Command of the relief army to Kerak was handed to Raymond of Tripoli accompanied by the now blind and partly paralysed king in a litter. After the siege had been relieved, Guy, joined by his wife Sybil, shut himself in his city of Ascalon, risking civil war by defying Baldwin’s attempts to strip him of his fiefs. The process of annulment also ran into the ground. But Guy’s hopes of rule seemed at an end.43

When the king despatched the Patriarch Heraclius to Europe in the summer of 1184 to try to induce a western ruler, perhaps one of Baldwin’s Angevin cousins, to come east to assume the regency, the political landscape appeared transformed. The regent of the year before was persona non grata; civil war had narrowly been avoided; Guy and Sybil had effectively been excluded from the succession that now hung on the life of an increasingly infirm leper and a weak child. When the king suffered another relapse in the winter of 1184–5, Raymond of Tripoli resumed the regency he had vacated over eight years before, although under restrictive terms, with Joscelin of Courtenay acting as young Baldwin V’s guardian. Acknowledging the fragility of succession arrangements, the High Court agreed that Raymond would retain the regency for ten years unless the young Baldwin died, in which case the competing claims of Princesses Sybil and Isabella would be adjudicated by the pope, the emperor of Germany and the kings of France and England. The earlier scheme of trying to attract a western regent was abandoned. Heraclius had met with no success, not having anything to offer western rulers other than temporary command of a fragile monarchy, a fractious nobility and a menacing enemy. The 1184–5 mission foundered on Jerusalem’s traditional diplomatic conundrum. Outside assistance was sought but with political strings protecting the power of the local royal family and nobility, hardly an attractive proposition. Paradoxically, the new succession arrangements in 1185 merely confirmed Jerusalem’s insularity.

The divisions within the ruling elite remained. Raymond held the regency, but Sybil was still married to Guy with her son, young Baldwin, in the custody of her uncle, Joscelin. Many suspected, possibly correctly, that Raymond still harboured designs on the throne while Princess Isabella’s party openly supported a settlement that denied the rights of Sybil and Guy. This time Baldwin IV did not recover. By 16 May 1185 he was dead.44 The crisis within Outremer deepened precisely at a moment of opportunity. Saladin spent the year from spring 1185 to 1186 occupied with his attempts to subdue Mosul and northern Iraq. In December 1185 he fell gravely ill. Out of action for three months, his life despaired of, Saladin’s empire seemed about to fall apart. However, before leaving for Iraq, the sultan had once more agreed a truce with Raymond of Tripoli. Consequently, the Franks did nothing to intervene, despite the arrival of a few crusaders in the wake of Heraclius’s embassy. The flaw in Raymond’s pacific policy was exposed when, on his recovery in March 1186, Saladin finally annexed Mosul.45 The encirclement described by William of Tyre was complete, and the Franks had done little to prevent it.

The death of the eight-year-old Baldwin V at Acre in the summer of 1186 drove Jerusalem near to civil war. While Raymond assembled a general council of the kingdom’s barons and clergy at Nablus, perhaps hoping to be elected king himself, Sybil’s partisans gathered at the Holy City for the young king’s funeral. With Sybil were Guy, the masters of the military orders, Reynald of Châtillon, the Patriarch Heraclius and Baldwin V’s paternal grandfather, William III of Montferrat, a veteran of the Second Crusade who had retired to the east in 1185. After the obsequies, despite the objections of delegates from Nablus, they proceeded to choose Sybil as queen. There was less enthusiasm about Guy becoming king. Before she was crowned, Sybil promised to divorce Guy on three conditions; their children (all daughters) were to be declared legitimate; Guy was to remain count of Ascalon and Jaffa; and Sybil was to have a free choice of new husband. However, once crowned by the patriarch, Sybil promptly selected Guy. This coup cannot have entirely pleased her supporters, but Sybil had shown that, like her father and brother, she understood her rights, knew the law and was prepared to impose her will.

In any circumstances, Sybil’s election would have proved contentious given the twists in the plans for the royal succession over the previous decade. Her appointment of Guy as king and his consecration by Patriarch Heraclius displayed conjugal devotion but no political tact. Raymond of Tripoli’s assembly at Nablus included the other claimant, Isabella and her husband, Humphrey of Toron, with their supporters, the Ibelins. Barred from the Holy City when Sybil’s supporters barricaded the gates, they learnt of the coup through despatching a spy, a Jerusalem-born sergeant disguised as a Cistercian monk, who lurked in the precincts of the Holy Sepulchre to observe the double coronation. Once news reached Nablus, Raymond desperately proposed the assembled nobles crown Humphrey, but the young man refused to cooperate with a scheme that would have caused immediate civil war. With most of the other nobles at Nablus, Humphrey recognized that, with a king already crowned and consecrated, however hateful, they had little option but to acknowledge the fait accompli. He left for Jerusalem to pay homage to his new lord, thus ending any prospect of concerted resistance to Sybil’s coup. Most of the rest of the Nablus gathering soon followed. Only Baldwin of Ibelin and Raymond of Tripoli remained recalcitrant. At King Guy’s first meeting of the High Court, in a show of almost constitutional propriety, Baldwin refused homage and quit the kingdom for service in the principality of Antioch. By contrast, Raymond’s refusal to accept Guy provoked the king to threaten the count with military reprisal. Fearing an attack by Guy, Raymond showed his low level of statesmanship by concluding a personal deal with Saladin under which he accepted the sultan’s protection and a detachment of Muslim soldiers to strengthen his garrison at Tiberias. Whatever his feelings about Guy, however disappointed he was by having power once again, and probably for ever, dashed from his grasp, Raymond’s behaviour in 1186–7, as most unbiased sources agreed, was more than selfish. It was treason.46

THE BATTLE OF HATTIN AND THE FALL OF JERUSALEM

The general truce with Saladin was due to expire a week after Easter, 5 April 1187. It would not be renewed. Restored to health and in control of an empire that stretched from the Nile to the Tigris, Saladin could now fulfil his political jihad rhetoric by military action against the Franks. In Jerusalem, Guy and his Poitevin cronies hardly made themselves popular by flaunting their new power and cornering lucrative patronage. In the winter of 1186–7, Reynald of Châtillon, frustrated by the truce from contesting Saladin’s attempts to consolidate his position in the Transjordanian desert, launched a successful raid on a rich Egyptian caravan travelling to Damascus. Guy’s lack of political grip was exposed by his failure to force Reynald to provide compensation or restitution to the sultan. Such diplomatic exchanges between Saladin and the Franks confirm the picture left by a surprised Spanish Muslim visitor to Outremer in the autumn of 1184 who noted how trade flowed freely across the Muslim–Christian frontier despite the war. Although each side took prisoners and slaves, Muslims were not molested in Christian lands and vice versa.47 Such accommodation may have helped persuade Raymond of Tripoli, a veteran of long captivity in Aleppo, that he would find Saladin a benign protector against his Christian king. His miscalculation no less than his ambition proved fatal.

When it became obvious that Saladin would launch an attack after the truce ended, King Guy realized he had to be reconciled with Raymond, whose control of Galilee was strategically vital. If, as it appeared, the count was prepared to allow access to Saladin’s forces, not only Galilee but the west bank of the Jordan and the coastal plain around Acre were exposed. While Saladin began hostilities in late April with an assault on Kerak, a delegation was sent by Guy to negotiate with Raymond at Tiberias. Their journey coincided with a raid into Galilee in 1 May 1187 by Saladin’s son al-Afdal, which was allowed free passage by Raymond in accordance with his treaty with the sultan. As the Muslim force, numbering perhaps 7,000, approached Nazareth, the locals appealed for aid to a contingent of the royal delegation led by Gerard of Ridefort, Master of the Temple, and Roger of Moulins, Master of the Hospital. Nazareth lay outside Raymond’s territories and therefore outside his truce. The Masters managed to assemble a scratch force from nearby castles of about ninety Templar and Hospitaller knights, forty local knights and perhaps 300 mounted sergeants. Although hopelessly outnumbered, this small army, using its only possible tactic, attacked the Muslims at the springs of Cresson. Despite fierce fighting, the Christians were massacred, only Gerard of Ridefort and three other of the knights escaping alive. In the inevitable recriminations that followed, it was alleged that the intemperate haste of Master Gerard, against the advice of his fellow commanders, had precipitated the battle. Given the appeal from Nazareth, it is hard to see what else the Templars and Hospitallers were to do without contradicting their calling. Militarily disastrous, the heroism at Cresson soon earnt the fallen knights the accolade of legend and martyrdom, their feats admiringly retold to inspire the endeavours of troops from the west during the long siege of Acre three years later. More immediately, the victorious Muslims withdrew across the frontier carrying the heads of their slaughtered foes on the ends of their spears.48

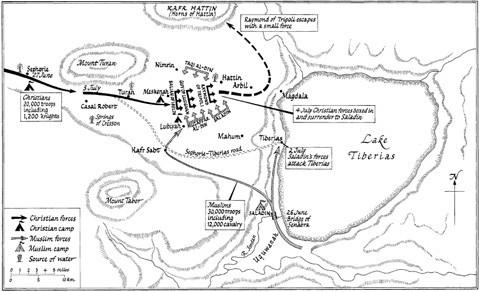

While the disaster at Cresson on 1 May 1187 significantly weakened Jerusalem’s resources, it produced political unity. By allowing al-Afdal’s troops to cross his lands, Count Raymond could not avoid shouldering blame for the massacre. Even his own vassals and the local militia in his territories turned against him. In the days after Cresson a hasty reconciliation was patched together between Raymond and Guy, the count’s truce with Saladin repudiated and the Muslim garrison at Tiberias expelled. Despite the tensions that simmered on the surface of baronial cooperation with the king, in the following weeks Guy was able to muster all the available troops from the kingdom, as well as some from Tripoli and Antioch. The Frankish host, one of the largest ever assembled, numbered up to 20,000, including around 1,200 knights. The force that Saladin led into Frankish territory around the southern end of the Sea of Galilee on 27 June 1187 was probably 30,000 strong. While the Franks, as in 1183, mustered at the springs of Sephoria, Saladin sent scouting and scavenging parties across the hills to provoke the Christians to break camp and to identify suitable battlefields. He then tried to lure the Franks into battle by leading a detachment of his main force against Tiberias on 2 July. The town fell the same day, the garrison under Raymond of Tripoli’s wife, Eschiva of Galilee, withdrawing to the citadel to endure a siege. On hearing of this, the Frankish high command met in the camp at Sephoria on the evening of 2 July to decide how to respond. On their decision hung the future of nine decades of western European settlement in the Near East.49

Later Frankish sources favourable to Count Raymond recorded that, after Raymond had persuaded King Guy to adopt the same tactics as four years earlier and refuse battle, the Master of the Temple late at night managed to change the king’s mind. Some Muslim accounts agree that Raymond urged the abandonment of Tiberias, which, he hoped, would lead to the dispersal of Saladin’s army, eager to return home safely with their booty, only to be contradicted by Reynald of Châtillon, who reminded the king of Raymond’s recent treachery and alliance with the enemy. Saladin’s secretary, Imad al-Din, by contrast, portrayed Raymond as taking the lead in persuading Guy to march out to relieve Tiberias.50 Whatever the immediate arguments and assessment of risks, Guy can hardly have avoided an unpleasant sense of déjà vu. In 1183, in similar circumstances, he had been vilified and hounded from office after failing to engage Saladin’s army even though he had kept the Frankish army intact and largely unscathed. Any advice he now received from political enemies, especially Raymond, must have appeared tainted. Aggression had served the Franks well in the past; Reynald of Châtillon was living proof of that. Sephoria lay just under twenty miles from Tiberias, just possible to reach in a day of forced march across the hilly terrain. If not, the substantial springs at Hattin, just over a dozen miles distant, offered refuge for a bivouac. The Frankish army was formidably large, with experienced leaders and seasoned troops. Despite the subsequent verdicts of events, Guy’s decision during the night of 2–3 July to break camp and march to Tiberias may not then have appeared foolish or doomed. Two years later, when he led a tiny Christian army to begin the siege of Acre, an apparently far rasher decision led to ultimate success. However, in the Galilean hills in July 1187, once committed, Guy had no prospects of reinforcement and few of ordered retreat. His choice of battle consciously provoked a confrontation that would be decisive, whatever the outcome.

The Franks left Sephoria early on 3 July, heading towards the small spring at Turan about a third of the way to Tiberias. Progress was slow and before nightfall stopped altogether. Saladin broke off his siege of Tiberias and organized his army to meet the advancing Franks. Once the springs at Turan had been passed, the Franks found themselves attacked from the right flank and rear. The sheer weight of Muslim numbers slowed the Franks until they reached Maskana on the western edge of the plateau that looked down on the Sea of Galilee. Here the leadership once more seemed at odds, whether to attempt to force their way eastwards down from the plateau to Tiberias that night, or to turn aside northwards to the large wells at the village of Hattin. In the end, they did neither, Guy ordering a halt at Maskana. The decision to camp for the night on the arid plateau with little or no water may have come from confusion and hesitancy. But Guy may have had no option. Enemy numbers harrying the army had slowed progress almost to a standstill, preventing it from reaching the springs at Hattin and threatening to turn a descent to the Sea of Galilee into a massacre or rout. The Franks do not seem to have successfully reconnoitred the enemy’s strength. If they had known how heavily the odds were stacked against them, the decision at Sephoria may have been different.

By the morning of 4 July, the Franks found themselves surrounded. Their only, slim chance of success lay in pressing on towards the fresh water of the Sea of Galilee in the hope of manoeuvring the enemy into a position where a concerted cavalry charge could be mounted. The Frankish vanguard under Raymond of Tripoli made an early attempt to break the stranglehold, but the Muslims merely opened ranks, allowing the count and his followers to escape, an act that confirmed for many Raymond’s treachery. Completely encircled, constantly harassed by scrub fires and hails of arrows, the Franks avoided total disintegration by establishing themselves on the Horns of Hattin, where the remains

9. The Hattin Campaign, July 1187

of an extinct volcano surrounded by the ruins of Iron Age and Bronze Age walls offered some protection. Here both cavalry and infantry made their last stand. As in the similar circumstances when the Antiochene army had been surrounded at the Field of Blood in 1119 and Inab in 1149, the outcome could hardly have been in doubt. Yet, even in extremis, the Christian knights refused to submit. At some point, elements of the rearguard under Reynald of Sidon and Balian of Ibelin, who had borne the brunt of attacks throughout the previous day’s march, managed to break out through the Muslim lines. During the withdrawal to the Horns, a Templar attack failed to disturb the surrounding cordon though lack of support. At the end of the battle, fighting exhaustion and despair, King Guy led at least two charges from his fortified base directed against Saladin’s personal bodyguard, his final throw to reverse the impending defeat. It was later reported that these attacks, even from so desperate a position, alarmed the sultan.51 Only when the remaining Frankish knights, having dismounted to defend the Horns on foot, were overwhelmed by thirst and fatigue as much as by their enemies, did the Muslims penetrate their final defences. Lack of water may have caused the collapse of horses as well as their riders, preventing further resistance. Guy and his knights were found slumped on the ground, unable to prolong the fight. Before these final moments, Frankish morale was destroyed by the capture of the relic of the True Cross and the death of its bearer, the bishop of Acre. This relic, discovered in the days after the capture of Jerusalem in July 1099, had regularly been carried into battle by the Jerusalem Franks as a totem of God’s support and promise of victory. Its loss, even more than the defeat itself, resonated throughout Christendom, raising the military disaster into a spiritual catastrophe.

Perhaps one of the most surprising aspects of the annihilation of the Frankish host was the numbers of survivors from the highest ranks of the nobility amid the carnage of thousands. Among the Frankish lords on their way to captivity Saladin had ushered to his tent after the battle were King Guy, his brother Aimery, Humphrey of Toron, Reynald of Châtillon, Gerard of Ridefort and old William of Montferrat, effectively most of the governing clique. By contrast, 200 captured rank and file Templars and Hospitallers were butchered amateurishly, almost ceremonially by Muslim Sufis, while infantry survivors were herded off to slave markets across the Levant. Alone of the grandest prisoners, Reynald of Châtillon was executed, possibly by Saladin himself, after an elaborate charade in which the sultan expressly denied Reynald formal hospitality in the form of a drink that was offered round the other captives. The gesture was of revenge on an infidel aggressor who had dared to take war to the holy places of Arabia. The ritualistic manner of his killing as remembered by Saladin’s secretary, who was present, suggested this departure from normal practice followed the needs of propaganda rather than anger. Saladin was the most calculating of politicians. He needed a head. Reynald’s was the obvious victim. In western eyes, his death transformed this grizzled veteran of Outremer’s wars into a martyr whose fate was promenaded to encourage recruitment for the armies that hoped to reverse the decision of Hattin.52 Meanwhile, before leaving the battlefield, Saladin ordered a dome to be constructed to celebrate his victory; its foundations survive to this day. Less permanent testimony to the great battle presented itself to the historian Ibn al-Athir, who crossed the battlefield in 1188. Despite the ravages of weather, wild animals and carrion birds, he ‘saw the land all covered with bones, which could be seen even from a distance, lying in heaps or scattered around.’53

The completeness of Saladin’s victory was soon apparent. The army destroyed at Hattin had denuded the rest of the kingdom’s defences. Saladin’s progress was cautious but triumphal. Beginning with the surrender of Tiberias on 5 July and Acre on 10 July, he mopped up most of the ports within weeks, including Sidon (29 July) and Beirut (6 August). Tyre survived, and then only because of the arrival from the west of Conrad of Montferrat, son of the captured William and uncle to the dead Baldwin V, in mid-July. Most of the castles and cities of the interior fell, with the exception of the great fortresses of Montréal, Kerak, Belvoir, Saphet and Belfort. Northern Outremer awaited its turn. On 4 September 1187, Ascalon surrendered after a stiff fight, followed by the remaining strongholds in southern Palestine. After negotiations that had seen the sultan enhance his reputation for magnanimity by allowing the Queen Dowager Maria safe conduct from Jerusalem to Tyre, on 20 September Saladin invested the Holy City.54 The garrison was commanded by Patriarch Heraclius, Balian of Ibelin, recently arrived from Tyre, and only two other knights. After a spirited show of resistance, and dramatic penances by the civilian population, the end came by negotiation. Saladin accepted payment for the release of most

10. Saladin Captures Jerusalem, September–October 1187

of the besieged Christians, a contrast with the events of July 1099 that he was not slow to point out. Jerusalem opened its gates on 2 October. Saladin milked the symbolism of his triumph. The cross the Franks had erected on the Dome of the Rock was cast down; the al-Aqsa mosque was restored and Nur al-Din’s pulpit from Aleppo installed; the precincts of the Haram al Sharif purified, the sultan and his family playing a conspicuous role; prominent Frankish religious buildings, such as the house of the patriarch and the church of St Anne, were converted into Islamic seminaries or schools. On 9 October, Friday prayers were resumed in the al-Aqsa. The Holy Sepulchre was spared, some said out of a pragmatic understanding of the importance of the site not the building for Christian pilgrimage, from which in the future the sultan could profit. However, the Latin clergy were expelled. Saladin had fulfilled his titles not just as victorious king, al-Malik al-Nasir, but as Restorer of the World and Faith, Salah al-Dunya wa’l-Din. It was the pinnacle of his career.