46

After the defeat of the workers’ uprising in June 1848, a frightened French bourgeoisie and peasantry elected Louis Napoleon to the presidency, then acquiesced when he overthrew the newly established republic and declared himself head of a Second Empire. As Napoleon III he swiftly established an authoritarian state and then, power secured, commenced the reconstruction of Paris.

In June 1853 the emperor handed a map of the capital to Baron Georges Eugene Haussmann, his newly appointed prefect of the Department of the Seine. On it he had sketched a network of wide, straight boulevards he wanted Haussmann to ram through the old city center. His goals were threefold: to unblock clotted medieval capillaries that were obstructing the circulation of commodities; to shift the city’s primary link to the outside world, from the Seine River to railheads converging on Paris from the countryside; and to forestall future construction of barricades and allow the emperor to mow down his enemies with artillery.

Haussmann duly plowed Napoleonic avenues straight from the new train stations to the commercial center, treating Paris as an engineering obstacle. The process deindustrialized much of the inner city and forced many working people to the periphery. As one class went out, another came in. The bourgeoisie roosted along the new boulevards in grand new apartment houses—modeled on the palais of urban aristocrats—whose heights and facades were reassuringly regulated by the state.

The state also undertook massive infrastructure projects: it built Les Halles and other giant markets, dug an enormous maze of underground galleries with space for sewers, water lines, and gas pipes; and made the Bois de Boulogne—with its curving roads, lakes, and bridle and pedestrian paths (some staked out by the emperor himself)—the new standard for metropolitan parks. Indeed command of the authoritarian state was crucial to every aspect of this urban renewal enterprise, from overbearing small property owners who resisted improvements, to mobilizing a scheme of debt financing, to promoting better housing for working people in an attempt to win their support.

The Parisian model would be copied repeatedly in the ensuing decades, not only by French provincial cities but by Brussels, Stockholm, Barcelona, and Madrid; soon Mexico City would be graced by Parisian boulevards (courtesy of the French-installed Emperor Maximillian). But it would not be copied in New York. There would be no grand design, for there was no grand designer, no political authority able or willing to unilaterally reorganize the flow of people and goods or impose a unified order of architecture. New York’s bourgeoisie, inconvenienced but not as yet significantly threatened from below, retained their republican distaste for centralized authority. When Lajos Kossuth came to town in 1851, the leader of Hungary’s rebellion against Austrian and Russian despotism was given a hero’s welcome at Castle Garden, on a par with those afforded Washington and Lafayette.

New York’s merchants, bankers, and industrialists were content to pursue their interests within the framework of a democratic polity, in part, because they had done so quite successfully, certainly at the national and state levels. Though differing sectors of the city’s propertied classes had different and sometimes opposing interests, and though New Yorkers in Washington had to negotiate with southern slaveholders and western farmers, and in Albany to tussle with upstaters—overall, the results had been satisfactory. Governments provided banking and currency legislation, tariff laws, protection for investments (especially in western land), judicial procedures for enforcing contracts, land for railroads, and subsidies for steamship operators. Much of their port’s expansion in this era was underwritten by the federal government. The U.S. Coastal Survey charted a new channel into the harbor; federal engineers cleared away obstructions in the Hudson and East rivers; federal largesse underwrote lighthouses and provided half a million dollars for work on the harbor’s forts and Navy Yard. Clearly, there seemed to be no inherent contradiction between capitalism and popular suffrage.

To sustain their access to and influence upon national and state governments, bourgeois New Yorkers participated personally in government, often serving as congressmen or state legislators. Chiefly, however, the wealthy worked in and through political parties, though continuing to differ on which was more suited to their interests. In the early 1850s, perhaps 75 to 90 percent of the merchants, industrialists, and bankers active in party politics were Whigs—attracted particularly by that party’s support for infrastructure development. Still, the oft repeated line “The Democratic merchants could have easily been stowed in a large Eighth Avenue railroad car” was seriously overstated, for New Yorkers were powers in the Democratic Party too (beguiled by its antitariff policies, among other things). Democrats, like Whigs, established their national headquarters in New York, for ease of access to campaign contributors and organizational talent: banker August Belmont, head of the Democratic National Committee, was instrumental in running and bankrolling James Buchanan’s presidential campaign.

TAMMANY’S TOWN

In New York City itself, however, the upper classes were far more ambivalent about democratic politics. From their perspective, municipal government had fallen into the wrong hands. Once upon a time wise and enlightened gentlemen like themselves had ruled in the public interest. Now, as they saw it, sleazy self-interested politicians had secured a lock on local affairs.

The mayoralty, to be sure, remained a bulwark of respectability throughout the period, as both parties felt impelled to select leading businessmen as nominees. The problem lay with the Common Council. Between 1838 and 1850, the percentage of merchants serving in this body dropped by half, to 15 percent. The ranks of aldermen and assistant aldermen were dominated by ambitious petty entrepreneurs (slaughterhouse operators, grocers, dealers in coal or hardware) or skilled craft workers (boatbuilders, carpenters, printers, sailmakers, hatters, tailors, saddlers, bakers, and chairmakers). Many councilmen, officeholders, and party activists had their political base in the liquor trade; it was said that one way to break up a meeting of Tammany’s Executive Committee was to open the door and yell, “Your saloon’s on fire!”

Such men rose to power not from boardrooms or drawing rooms but from the intensely maculinist working-class streets. Rising politicians like William Magear Tweed often developed personal followings—as the gentry once had—by displaying their courage and generosity in leading volunteer fire companies. Tweed, born in 1823 to a Protestant, third-generation Scottish-American family, grew up on Cherry Street, studied bookkeeping, worked in the brushmaking business in which his father owned stock, then joined the family chairmaking firm. A brawny young man with clear blue eyes, an amiable smile, and a fabulous memory for names and faces, Tweed was a gregarious chap (and a good dancer to boot). In 1847 he enlisted in the International Order of Odd Fellows; he was later initiated as a Mason and in 1849 joined some friends in organizing a fire company. He seems to have chosen its name—the Americus Engine Company, Number 6 (more popularly known as “Big Six”)—and its symbol as well, a snarling red tiger. In 1850, Big Six’s seventy-five red-shirted, intensely clannish members elected him foreman, and Tweed, dashingly attired in white firecoat, led his loyal men in “running with the machine” to battle blazes. Unfortunately they also battled other companies, and in 1850 chief engineer Alfred Carson, who personally accused Tweed of leading an ax-wielding assault on rivals, managed to get him expelled. Still, his exploits had provided a stepping-stone into politics, by bringing the vigorous and ambitious twenty-six-year-old businessman to the attention of Seventh Ward Democratic politicians. In 1850 they ran him for assistant alderman. It was a Whig year, and Tweed lost, but the following year he ran for alderman and won, embarking on a fateful career.

Like fire companies and saloons, gangs were important recruiting grounds for party activists. Candidates for ward offices were chosen at wide-open, walk-in primaries, held in local saloons and hotels. These meetings also selected the ward’s delegates to nominating conventions, which in turn proposed candidates for state offices, county offices, city departments, city judgeships, the U.S. Congress, and the mayoralty—at a time when nomination was often tantamount to election. Those intent on dominating these gatherings—held during August and September, when respectable folk were out of town—simply packed them. For the requisite muscle, political entrepreneurs turned to “shoulder-hitters,” the same men who for a price would keep opponents from the polls and guard (or stuff) ballot boxes.

Political gangs were, in their own way, open to talent. In the late 1840s John Morrissey, a Troy ironworker, came down to New York, walked into Captain Rynders’s Empire Club, and offered to fight any man in the house. He was immediately beaten to a pulp, but Rynders—Tammany boss of the Sixth Ward—admired his bravado and offered him a spot as a shoulder-hitter and emigrant runner (a task that involved meeting immigrants at the docks, getting them naturalized, and finding them homes and jobs, in return for their votes).

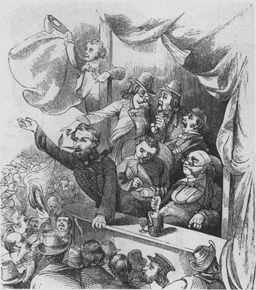

Boss Tweed as foreman of “Bix Six.” Engraved portrait. (© Museum of the City of New York)

The Whig Tribune was correct in claiming that Democrats regularly rigged elections with the aid of “a dozen of beastly ruffians in each ward, hired to do the voting and knock down any one who should presume to interfere with the play.” But Whigs too turned to gang leaders, like “Butcher Bill” Poole, a celebrated brawler and eye gouger who ran his own Ninth Ward gambling and drinking place. A nasty piece of work, whom even his friends considered deceitful and bloodthirsty, Poole periodically set his thugs to contesting Morrissey’s men at the polls, until his assassination in Stanwix Hall in 1855, which some suspected Morrissey of masterminding.

Once successful, an alderman had much more to offer his followers than bonhomie and booze. Tammany councilmen, in particular, were ardent in protecting immigrants and their customs and regularly denounced nativists as “bigots and fanatics in religion.” They also attended diligently to immigrant sensitivities: green flags and much bombast flew from the steps of Tammany Hall on St. Patrick’s Day. The newcomers were not naive about the depth of this commitment, but, as the Irish American noted, though the Democrats had their anti-Irish prejudices, at least “they act as if they loved us.”

In the end, however, patronage was the lubricant that kept the still-rickety political machines in running order. The mayor appointed all policemen but had to choose them from a nominating list submitted by ward aldermen; the need for annual reappointment kept cops attentive to councilmen’s wishes. Supporters could also be rewarded with carting licenses, saloon licenses, and appointments as health wardens, street sweepers, and a myriad of other minor city positions. Councilmen handed out municipal contracts for school, dock, sewer, and street construction to builders, utilities contractors, stonemasons, and carpenters (a good many of them Irish), who returned the favor by mobilizing their grateful employees at election time.

Aldermen, imbued with the era’s entrepreneurial spirit, also asked what government could do for them, and found many answers. They could require contractors to present padded bills and then split the excess among themselves. They could award contracts to firms run by relatives, or in which they were partners, or owned entirely by themselves. The really big money, however, came from the ability of a newly autonomous political elite to force the city’s economic elite to pay for things it had once commandeered more directly. Market-oriented politicians set about selling off public assets to the highest bidder.

There was plenty to sell. The Common Council merrily leased out city piers, sold off profitable riverfront properties, and granted ferry franchises to a favored and responsive few. Corruption was hardly new, of course—“There never was a time when you couldn’t buy the Board of Aldermen,” Tweed once remarked—but it was the arrival of the street railroads, with their attendant scramble for franchises, that brought civic chicanery to new heights (or depths).

Since the Harlem Line had been initiated back in the 1830s, aldermen had generally rejected requests to run horsecars through the city’s streets, usually at the behest of politically influential omnibus operators determined to avoid competition. As the potential profits in accommodating the railroad interests became clear, they changed their minds. First, however, they had to beat back proposals that the city itself lay out a unified rail system, to keep fares low and earn profits for the city. Laissez-faire aldermen indignantly denounced public ownership—it would never be able to impose “a system of responsibility that private enterprise alone can arrange and insist upon”—and then got down to the lucrative business of handing out franchises to clamorous (and rivalrous) entrepreneurs.

The turnaround on railroads largely coincided with the accession to power—in the November 1851 elections—of brushman-chairmaker William Tweed and a host of other petty entrepreneurs including a tobacconist, saloonkeeper, stonecutter, butcher, saddler, timber dealer, fishmonger, fruit vendor, and proprietor of a livery stable: men who had watched their “betters” get rich and were determined to get their cut. Working amid the cloud of lobbyists that swarmed each day about City Hall, the Common Council set about earning its nickname of the “Forty Thieves.”

Among other initiatives during their two-year run for the money (1852-53), the magistrates spurned an offer to pay the city fifty thousand dollars for the exclusive right to collect dead animals from the streets and gave the contract instead to one W. B. Reynolds, paying kirn sixty-three thousand a year (out of which, a grand jury later found, he made disbursements to aldermen and the city inspector). The Common Councilmen leased city-owned piers at giveaway rents to favorites. They sold off Gansevoort Market, among the most valuable pieces of real estate in the city, for much less than it was worth, allegedly pocketing between forty-five and seventy-five thousand dollars for themselves. Witnesses testified before a grand jury that ferry leases were awarded in return for payoffs. In the case of the Wall Street ferry, the aldermen overrode the mayor’s veto and gave the plum to Jacob Sharp, one of their favorites, for much less than other applicants were willing to pay, then lowered his rental costs still farther the following year. Council members also perfected the art of “ringing the bell”—proposing nuisance ordinances that brought the threatened parties running with payoffs.

Most significant, 1852 brought a deluge of railroad projects, and an obliging council liberally handed out charters—which were to be held in perpetuity—on terms unfavorable to the city. One line up Second Avenue went to a group that included Tweed’s father-in-law; another, up Third, was awarded to a combination that included prominent Democratic politicians. Thus did the council establish—without even minimal planning, much less coordination on a Haussmannesque scale—the transportation system that would dominate the city for decades. In addition, its charters created quasimonopolistic agglomerations of corporate power, like the Third Avenue line (capitalized at over a million dollars), whose impact on the city, including the flagrant corruption of civic politics, would long outlast Tweed and his cohort.

MUNICIPAL POLITICS INDICTED

Many businessmen pragmatically accommodated themselves to this de facto partnership with politicos. For those in a position to outbribe their rivals, the situation had the positive advantage of allowing their money to talk loudest. Councilmen were also useful at ensuring that unwanted things did not happen. Whether from principled attachment to laissez-faire dictums or inspired by more tangible inducements, aldermen routinely blocked government actions (housing codes, labor laws, horsecar construction) that might hamper favored entrepreneurs. In 1850, against the backdrop of widespread radical and union agitation, a newly established Gas Consumers Association demanded the Common Council build and operate a municipal gas plant. Hostility to the two old monopolies that divided the business had long been building. The rates of the New York Gas-Light Company (1823), which supplied districts south of Grand Street, and the Manhattan Gas-Light Company (1830), which handled territory north of Grand, were much higher than those charged by counterparts in Philadelphia. Friendly authorities quashed the program for public power, however, and indeed forestalled the chartering of any new competitors—until 1855, when powerful entrepreneurs won establishment of Harlem Gas and Metropolitan Gas. Even then, City Bank’s Moses Taylor, a Manhattan Gas director, proved able to negotiate an amicable agreement with the new outfits, forestalling potentially ruinous competition (and lower gas prices as well).

If particular enterprisers were prepared to treat corruption as a routine cost of doing business, a far broader constituency was enraged by what it considered a more pernicious consequence: higher taxes. The Forty Thieves managed to increase city spending by 70 percent in their two years—including a marked upswing in expenditures for gas and lamps, street cleaning, and the purchase of real estate (up 400 percent)—and taxes had jumped accordingly, up by 54 percent between 1850 and 1853. The Common Council had also raised money by drawing on new techniques of railroad finance to sell revenue anticipation bonds. This practice had been going on since 1843, but where it once covered just 27 percent of the city’s expenditures it now (by 1856) paid for 47 percent of a sharply higher outlay, calling into question the security of investments in city bonds.1

Lost in the outcry of property-owning taxpayers was any awareness that while corruption certainly siphoned off funds, most city money went for street extension and paving, police stations and prisons, and many other items for which the bourgeoisie itself had pushed. Alderman Tweed, responding to critics at the end of his term, noted indignantly that half the appropriations made by the Common Council in 1853 were for mandated items, especially the almshouse and schools. “I ask the people,” Tweed went on, “if a city such as ours, daily receiving an immense population of the idle, degenerate, vicious, and good from all parts of the world, could be governed at less expense?”

Reformers worried about more than taxes, however. They were dismayed by what they saw as the Forty Thieves’ encouragement of lawlessness and disorder. In the summer of 1852, for instance, the aldermen used their judicial powers to discharge over fifteen hundred of the two thousand men arrested for street fighting and disorderly conduct—many of them loyal party activists—at just the moment when an epidemic of “garotting” (mugging) seemed to be sweeping Manhattan. Reformers were also appalled that council-dominated police officers were taking money to leave underground entrepreneurs alone. This was evident from the throngs of thimble-riggers and three-card monte men who worked the streets openly (and particularly thickly near City Hall) and from the gambling joints on Barclay, the Bowery, and Ann Street (between Broadway and Nassau) that were jammed with volunteer firemen, shoulder-hitters from Tammany Hall around the corner, and gangsters from the Bowery and the Points.

Cordial relations with politicians were key to the gamblers’ survival, and indeed the line between the two was often hard to spot. After working for Rynders, John Morrissey went on to a career as a bare-knuckle prizefighter; he took on Yankee Sullivan in an indecisive brawl in 1853, which the umpire gave to Morrissey, and no sooner had he become top dog of the boxing world than he opened his own faro parlor and taproom. Michael Norton, another pugilistic politician, established an entire community of outlaws on the far westerly end of Coney Island (soon known as Norton’s Point), which quickly attracted gamblers, sporting men, and others with a distaste for law and order.

If bourgeois New Yorkers were alarmed at losing control of the police—an increasingly critical government agency, given employers’ strained dealings with labor unions in the mid-1850s—they were equally dismayed by deficiencies in the fire department. Between 1837 and 1848, notwithstanding the introduction of Croton water, New York suffered twenty-five hundred fires, and some of the worst took place in downtown business wards: the great blaze of 1845, which rivaled that of 1835, destroyed one hundred buildings. Disgusted observers blamed brawling (a la Tweed), the companies’ steadfast refusal to introduce steam engines (the first was not adopted until 1857 and was the gift

of a fire insurance company), and, most of all, the councilmen who protected the politically potent firemen.

Environmentalist reformers joined the indictment of municipal politics. They insisted that inefficiencies in sanitation, and thus the soaring mortality rates, stemmed from aldermanic disbursal of cleaning and scavenging contracts to incompetents or crooks. In 1852 John Griscom denounced as well the failure of council-appointed health wardens to enforce such sanitary laws as existed. Merchants in general increasingly feared (as one said in 1854) that “men will go with reluctance to make money in a city where pestilence or violence renders life unsafe.”

The growing power of politicians, moreover, seemed to coincide worrisomely with the growing public presence of immigrants. The St. Patrick’s Day parade had been a small and insignificant affair up until 1849, when it suddenly swelled to a reported fifteen hundred marchers, in part because of a feisty newcomer, the Laborers United Benevolent Association. By 1851 seventeen societies, including other new labor organizations, had formed a Convention of Irish Societies, which reorganized the parade under a grand marshal. By 1853 it had grown big enough to bring city business to a virtual standstill and politically puissant enough so that when St. Patrick’s Day paraders tromped into City Hall Park, they were reviewed by the mayor and city officials.

Such acknowledgment grated on nativist nerves, but it was when the Irish decided that same year to march on July 4 as well—staking a claim to American nationalism—that violence erupted. Anti-Catholics had been wrought up already by the arrival in June 1853 of papal nuncio Monsignor Gaetano Bedini, a notorious reactionary who had helped brutally suppress the 1849 republican revolution in Rome. Nativists were convinced his mission was (as Bishop Hughes had boasted) to subjugate the American republic. Tempers were taut, therefore, when the Ancient Order of Hibernians announced it would hold its own Independence Day parade, which would then link up with the official one.

Early on the Fourth, five hundred marchers clad in green scarves and green badges set out from the Hibernians’ headquarters, arrayed in eight divisions. Proceeding west on 14th Street toward Eighth Avenue they held aloft a twelve-foot-high banner depicting George Washington shaking hands with Daniel O’Connell. At 10:30 A.M., the Hibernians reached Abingdon Square in Greenwich Village, a community still dominated by native-born artisans and professionals. An altercation with a stagecoach driver annoyed at having his way blocked by Catholics exploded into violence. Led by a notorious nativist gang called the Short Boys, a huge crowd of local nativists, including local volunteer firemen summoned by ringing bells, descended on the marchers, screaming, “Kill the Catholic sons of bitches!” and brandishing knives. A mass of enraged men—Hibernians in green scarves, nativists in red shirts—were swirled in battle when the unabashedly nativist Ninth Ward police arrived and waded in against the Hibernians. Scores of Irish were bloodied, their Washington-O’Connell banner was shredded, and thirty of their number were subsequently indicted for riot.

Street skirmishes became commonplace that fall when evangelical Protestant preachers, most of them obscure artisans and laborers, ventured into Irish neighborhoods spewing incendiary views about the “Scarlet Whore of Babylon” and the morals of Irish women. Other preachers held forth at the East River shipyard owned by Mayor Jacob Westervelt, where they were hailed by throngs of cheering Protestants and heckled by crowds of Catholics, in assemblages reaching twenty thousand people.

Kleindeutschland too was on the move, as were its enemies. For their 1851 celebration of Pentecost, commemorated in Germany by festivals in the woods, some ten to twelve thousand assembled at City Hall Park, then crossed to Hoboken. The Short Boys showed up and overthrew tables and insulted females until a disciplined contingent of Turners in sharply pressed white uniforms drove them off. When the revelers headed back to the ferry, however, the Short Boys struck again, reinforced by Jersey nativists armed with pistols, swords, clubs, and spike-covered poles. The Turners launched a counterattack, and a sanguinary two-hour battle ensued; at least one was killed and dozens wounded before the military arrived from Jersey City.

The Turners promptly demonstrated their fearlessness by returning to Hoboken for their own Turnfest, a gymnastics jamboree. It became an annual event, one of the most popular in German New York, and from then on Turners marched at the head and tail of almost all Kleindeutschland parades (except religious processions). In addition, the Germans formed Schiitzenvereine (shooting clubs) and militia companies. By 1853 there were seventeen hundred German militiamen, 28 percent of the city’s total force; added to the twenty-six hundred Irish militiamen and contingents of French, Scotch, Italians, Portuguese, and Jews, this meant that more than two-thirds of New York’s six thousand uniformed militia were foreign born. The immigrants were establishing their rights to city space; their enclaves would not be ghettos.

REFORM

In this atmosphere not only did Napoleon and Haussmann look good, but some New York elites looked with interest at a direct action model pioneered by their counterparts in San Francisco. In 1849 and 1851 the prominent men of that city had organized a Committee of Vigilance, which issued warnings to criminals, then banished some and hung others. Dissolved in 1853, it was reborn in 1856 as the San Francisco Vigilance Committee, still dominated by leading merchants. It not only hung crooks and shut up gambling houses but fought corruption in city government—by which it meant wresting control from the dominant Irish Catholic Democratic machine. This had been set in place back in 1849, when David C. Broderick, an old Tammany hand and Gold Rush migrant, had transplanted Manhattan’s political methodology, especially its ward-based apparatus, to the West Coast. Not only were the bulk of the vigilantes middle- and upper-class Protestants—either Whigs or nativists—but most of their victims were Catholics.

In New York, though some were tempted by vigilante or authoritarian models, most opted for exclusionary devices. In 1849 a group of nativists founded the Order of the Star Spangled Banner, a secret society with clandestine meetings, rituals, signs, distress calls, and handshakes. In 1853 the group was informally christened “Know-Nothings” by E. Z. C. Judson (Astor riot leader) after their habitual response to questions about their underground operations. The Know-Nothings’ aboveground operation, the American Party, aimed to eliminate all foreigners and Catholics from public office, to impose a twenty-one-year residency requirement for naturalization (time enough to reeducate victims of papist and monarchist delusions), to deport foreign paupers and criminals, to require Bible reading in the public schools, to ban the use of foreign languages from schools and public documents, and to break up all military companies “founded on and developing foreign sympathy.”

The nativists won support among respectable New Yorkers too, some of whom had been wondering if the city’s newest residents weren’t perhaps beyond redemption—so inferior to their predecessors, both morally and physically, as to constitute a separate species. Watching an Irish crew dig the cellar for his new home, George Templeton Strong remarked on the “prehensile paws supplied them by nature with evident reference to the handling of the spade and the wielding of the pickaxe.” The occupants of Union Square town houses and Fifth Avenue mansions were in fact nearly obsessed by the “brutish” or “simian” physiognomy of the Irish, vesting it with a range of political and social meanings: that Paddy was born, not made; that his physical and moral defects were hereditary; that like blacks, Indians, and women, he was inherently unsuited for republican citizenship. Yet despite some mutterings about disfranchising the immigrants, the city bourgeoisie still lacked the inclination to abandon republicanism—or the power to do so had it wished. Instead it chose to do combat in the political arena.

In 1852 William Dodge, John Harper, Stephen Whitney, and others determined to recapture the municipal ship from the pirates who had boarded and seized it launched not a vigilante group but a City Reform League. By March 1853 Peter Cooper had signed on as President (he would lead the reform movement for the next twenty years) and a host of dignitaries had agreed to serve as vice-presidents—including shipbuilder William Webb, rentier Peter Stuyvesant, Simeon Baldwin (then president of the Merchants’ Exchange), banker Moses Taylor, Times editor Henry Raymond, and several merchants, like William Aspinwall and Henry Grinnell, whose own methods in winning federal mail subsidies wouldn’t have borne close examination. Blasting the use of muscle and corruption, denouncing municipal extravagance, and warning that high taxes would drive businessmen out of the city, they set about the work of reform.

First they changed the charter. The City Reform League prevailed on the legislature to propose, and the electorate to ratify (in June 1853), a drastic reduction in aldermanic power. The Board of Assistant Aldermen was scrapped altogether and replaced by a sixty-man, annually elected Board of Councilmen—on the theory that so many councilmen could not be “bribed but in battalions.” (The penalties for bribery were strengthened, just in case.) This body was given charge of all legislation regarding expenditures—the aldermen being limited to suggesting amendments—and required to award all contracts in excess of $250 to the lowest bidder at public auctions.

On the law-and-order front, the councilmen were stripped of their right to sit as judges in municipal courts and lost the power to appoint policemen. Control of the force shifted to a Board of Commissioners (mayor, recorder, and city judges). Also in 1853, the police were given permanent tenure during good behavior and ordered into blue uniforms; in 1854, arrests jumped 40 percent.

The new charter also strengthened the mayor somewhat, by giving him a stronger veto that only two-thirds majorities of both legislative chambers could override. But the city’s chief magistrate was no Bonaparte. Since 1849 the nine executive departments had been controlled by independently elected heads, not answerable to the mayor, and they, not he, controlled most patronage, in conjunction with the legislature.

The charter secured, the City Reform League turned to the fall 1853 elections and backed those members of the regular parties (mainly Whigs) who agreed to run as reformers. In the nativist atmosphere, the reformers did well, with victory at the polls stemming in large part from a de facto alliance with the resurgent anti-immigrant movement. The Forty Thieves were swept out of office and into obscurity—except for William Tweed, who in 1852, while still an alderman, had run for Congress and won. The reformers were ecstatic; reclaiming the polity from the politicians seemed eminently feasible.

Holding it proved tougher. The new councilmen didn’t grant questionable franchises, nor did they interfere with the newly reorganized police department, yet neither did they succeed in holding down spending. Paying for those new policemen and the burgeoning school system helped boost taxes 25 percent higher in 1854 and 1855 than in Tweed’s two-year term. The disgusted Reform League repudiated its political progeny.

Worse, their alliance with the nativists, and the temperance forces active at the same time, tarnished their image, giving them a narrow and persecuting taint. Given that by 1855 nearly half of the eighty-nine thousand legal voters in New York City were naturalized immigrants, this boded ill. Their reputation was further sullied by continuing nativist street violence. In June 1854 a sailor named John S. Orr, calling himself the Angel Gabriel, clad himself in a long white gown, flourished a brass trumpet, and led a crowd of a thousand nativists to Brooklyn on Catholic-bashing expeditions. The Irish fought back with clubs and stones, then guns came into play, forcing Brooklyn’s mayor to call in the National Guard. Such disorders helped speed Know-Nothingism to total collapse the following year.

In addition, the reform movement split apart in 1854 when a critical mass of the membership, especially old Democrats like Peter Cooper and William Havemeyer, decided that Tammany had come up with a candidate they could live with: a businessman of considerable wealth and a reformer who promised to clean up New York City with Napoleonic efficiency.

“OUR CIVICHERO”

Fernando Wood had commenced his business career in the 1830s, as the owner of a grocery and grogshop near the waterfront, and his political career in 1840, when his immigrant longshoreman patrons sent him to Congress for a term. Returning to New York, Wood had invested his liquor store profits in three small sailing vessels and, by the late 1840s, established himself as a shipping merchant, leasing ships and engaging in the coastal trade with southern markets. A sharp practitioner, he was accused of fraud in 1839; although not convicted, he would be dogged from then on by a (probably deserved) reputation for duplicity. Nevertheless, Wood did well in the Gold Rush trade and parlayed his profits—and the comfortable inheritance of his second wife, Anna Richardson—into a still greater fortune by adroit land speculation. Beginning in 1848 with a substantial upper west side tract, he bought land and built and sold homes, offices, and stores in nearly every ward. (“I never yet went to get a corner lot,” Tweed said later, “that I didn’t find Wood had got in ahead of me.”) These profits in turn were pyramided into investments in banks, railroads and insurance companies, and by the end of the 1850s he was a millionaire.

In 1850 Wood ran for mayor as a “true friend of the Irish” but was beaten back, partly by allegations of business dishonesty: Wood, Philip Hone wrote, “instead of occupying the mayor’s seat, ought to be on the rolls of the State Prison.” But in 1854 he recaptured the Democratic nomination and won, despite hysterical opposition from nativists to the candidate of Rum and Rowdyism. His strongest support came from the working-class wards (particularly the Irish Sixth, where he harvested four thousand more votes than there were voters). His enemies, however— acombination of prohibitionists, Know-Nothings, and Whigs—secured control of the Common Council and many of the critical patronage-dispensing departments.

Until the very day of his inauguration, January 1, 1855, many considered Wood the incarnation of evil, a Cataline with a long and sorry record. Yet immediately on taking office, Wood became the very model of a reforming mayor. He announced his intention to establish frugal government and maintain public order. He commenced a modest crusade against prostitution in lower Broadway and violators of Sunday closing laws. He went on to call for clean streets, new stone municipal docks, effective building codes, sanitary police, market inspectors, metering of an expanded Croton water system, uptown steam railroads (and uptown development in general), a new City Hall, a full-size Central Park (resisting would-be trimmers), and creation of a great university and a free academy for young women. All in all he championed a thorough reconstitution of the city that would, he said, make New Yorkers proud of their “citizenship in this metropolis” and enable them to “say with Paul of Tarsus, ‘I am a citizen of no mean city.’”

Even beyond this astonishing advocacy of proposals advanced over the years by Griscom, Cooper, and others, Wood announced a determination to govern. Just as Louis Napoleon was beginning his top-down reconstruction of Paris, the new mayor declared he would vigorously make use of the powers provided his office by the new charter to bring efficiency and order to New York, and indeed appealed for still greater authority. “I am satisfied,” he proclaimed, “that no good Government can exist in a city like this, containing so many thousands of the turbulent, the vicious, and the indolent, without a Chief Officer with necessary power to see to the faithful execution of the laws.” In the short term, Wood set out to turn the newly reformed police department into a highly centralized and disciplined civic army, connecting all station houses to the chief’s office by telegraph. The Tribune was thrilled at the department’s new capability “of being quickly concentrated by the magical telegraph wires on any given part of the city” and pronounced it “a terrible warning to. . . the ruffianism which has so long beset our city.”

The reformers rubbed their eyes, convinced they were dreaming. But no, Wood had been transformed. He even looked the part: tall, erect, urbane, with a commanding presence. Strong was amazed that this “man whose former career shews him a scoundrel of special magnitude” had become “our Civic Hero.”

Not everyone was entranced. The more astute reformers noticed that Wood’s antivice crusades were highly selective. His men rounded up streetwalkers but left brothels alone, raided the grubbier gambling dens but not the fashionable establishments, and bypassed Sunday saloonkeepers who voted the right way. Nor did hard core prohibitionists appreciate the deft way he finessed a draconian 1855 temperance law, casting his refusal to enforce it on constitutional rather than proliquor grounds. In addition, his monopolization of patronage, reputed use of strong-arm tactics at the polls, and repeated demands for an increase in his constitutional power (especially greater control over the police) seemed to some to herald a turn to French-style despotism.

Equally disturbing was his continuing popularity with the immigrant laboring classes. Wood established a “Complaint Book” in which citizens could register charges against crooked or exploiting employers, or obnoxious policemen and public officials. He appointed Irishmen to the police in growing numbers (by 1855, they constituted 27 percent of the force and outnumbered native-born members in heavily Irish wards).

Temperance, but no Maine Law, Pi. Fay’s 1884 depiction of the interior of the Gem Saloon, a fashionably rococo establishment that stood on the corner of Broadway and Worth Street. The top-hatted man shaking hands in the center is Mayor Fernando Wood, who opposed adoption of a state prohibition law and subsequently refused to enforce it on constitutional grounds. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures)

Most alarming of all, when the economy buckled, Wood called for aiding the unemployed with public assistance and public jobs.

In the winter of 1854-55, the great boom faltered badly. A string of commercial failures and a flurry of frauds and defalcations failed to touch off a full-scale depression but did precipitate a recessionary crisis. Factories, shipyards, and the building trades laid off massive numbers of employees. As a cold wave drove the temperature to minus ten Fahrenheit, charities tried to succor the suffering. Soup kitchens set up by rich merchants fed twelve thousand a day—A. T. Stewart opened one in the basement of his Marble Palace—but most relief givers were quickly overwhelmed. The AICP warned in January it had nearly exhausted its treasury helping some fifty thousand needy, and issued what for the laissez-faire organization was a humiliating plea to the Municipal Almshouse Department to increase public spending on outdoor relief.

Meanwhile, thousands were listening to more radical solutions to their plight. Rallies in City Hall Park and elsewhere around the city hailed speakers who denounced unemployment, high prices and rents, and speculators in land and bread. Mass meetings passed resolutions calling on the city to “secure to us our right to labor” by providing jobs on public works, including an immediate start to construction on the Central Park reservoir “to furnish employment to those who do not covet the degradation of beggary.” Demonstrators called for an urban homestead act, asking the Common Council to distribute common lands to workers and appropriate half a million dollars with which to build “inalienable homes.” They also wanted evictions of the destitute stopped, with landlords to be indemnified out of public funds, and a three-million-dollar loan fund established to transport idled workers west. These were hardly extrava-

Labor demonstration in City Hall Park, demanding relief for the unemployed. From an 1855 nativist tract, The Crisis; or, the Enemies of America Unmasked. (Courtesy of American Social History Project. Graduate School and University Center. City University of New York)

gant demands, one shoemaker noted, at a time when “Louis Napoleon had given four millions and a half to build houses for the workingmen.”

The unemployed rebuffed the wealthy’s offer of charity and insisted on public aid as a citizen’s right. “Need pounds with heavy fists on the door of public attention,” thundered Wilhelm Weitling, “which has offered only beggars-soup in response. Beggars-soup! Beggars-soup!! In America it has already come to that.”

The Herald recoiled from demonstrations by “unwashed and greasy workmen” and attacked their presuppositions. It was a fallacy, the paper argued, that it was the business of the state to care for the unemployed. “This principle, which is of French origin, has been widely disseminated among the operative classes by a set of political imposters.” It was absurd; it flew in the face of modern science: “To render any class or set of men responsible for the existing state of things is obviously to ignore the first principles of political economy.”

Labor spokesman William West countered such laissez-faire objections from the standpoint of a well-thought-out, alternative moral economy. It was obvious that “private capital is insufficient to satisfy the demands of labor,” West said in laying a mass meeting’s proposals before the Common Council. “Unless you, therefore, substitute the public for private capital, in the employment of these thousands of compulsorily idle workmen, it must be apparent that the men cannot live except upon charity (which they will not ask and are very reluctant to receive) or by theft (which is their last alternative).”

Reformer Peter Cooper agreed, and in an open letter urged that the city either provide land or put men to work quarrying marble for the construction of new docks and piers. Even the Times came out cautiously for public works, while denouncing demonstrators as a “miscellaneous crowd of alien chartists, communists and agrarians.” But it was Mayor Wood who spoke most boldly of all, in his January 1855 inaugural during the height of the panic winter. “Do not let us be ungrateful as well as inhuman,” said the mayor, who supported Cooper’s dock-work plan. “Do not let it be said that labor, which produces every thing, gets nothing and dies of hunger in our midst, while capital, which produces nothing, gets every thing, and pampers in luxury and plenty.”

These opposing worldviews, poised for an all-out clash, never arrived at a confrontation. The economy lurched upward again. Unions returned to narrowly focused issues. Some radicals, discouraged, moved elsewhere: Joseph Weydemeyer headed west to agitate in 1856.

Wood pressed ahead with his reform program. When opponents in the state legislature threatened to curtail his power, particularly over the police, Wood was supported by two mass meetings of the wealthy and powerful including William Havemeyer, James Watson Webb, Commodore Vanderbilt, Horace Greeley, and City Reform League president Peter Cooper. Even the Times, more critical than most, remained beguiled by Wood’s energetic course: “Most of the objects of a city administration are far better carried out,” it declared in best Napoleonic style, “by a vigorous and arbitrary police system than by a representative assembly.” As his term ran out, a hundred wealthy bankers and merchants asked Wood to run again in 1856. Which he did, defeating his Know-Nothing opponent with heavy support from the East Side’s German and Irish precincts, helping send that party into steep and rapid decline. Taking no chances, Wood had also released some patrolmen from normal duties to help with his campaign and furloughed others on election day so that friendly hoodlums had a free hand menacing opposition voters. Despite some outcries, these lapses were not enough to alienate the bulk of the respectable classes, most of whom were overjoyed that Wood seemed capable of maintaining an electoral mandate from the poor at so little cost to the rich.

STATE OVER CITY

Balked in New York City, die-hard nativists, temperancites, and good-government men turned to Albany, where they staged not a Napoleonic coup but something almost as effective.

Upstate New York was a much more congenial stamping ground for such reformers. Not only were nativist and temperance forces far stronger in the countryside, but widespread rural animosity toward the burgeoning metropolis had created a host of potential allies. Upstaters denounced what seemed to them an urban trampling of the rights of man. On the one hand there was the expanding power of New York’s monied classes and the “subtle invading power of [its] gigantic corporations,” which actively threatened Christian and republican America. On the other there was the deplorable barbarism of the poor and the power of the political demagogues. Saving the republic required that the metropolis be brought under control of the good people of the state. As one upstate legislator declared in 1853, “the time has come when it is to be settled whether New York City is an empire—a community by itself.”

The vehicle for achieving an upstate-downstate alliance was a new political formation, the Republican Party. A northern phenomenon, it came together in New York State in September 1855 when a mix of Seward Whigs, Free Soil Democrats, and disaffected Know-Nothings joined hands on a variety of national issues, chiefly resistance to the western expansion of southern slavery. In the fall of 1856 state voters elected a Republican governor, John Alsop King (son of Rufus King and brother of banker James Gore King), and a Republican majority in the Assembly. In short order, Republicans in Albany set out to wrest New York City from the Democrats. Some were driven by dreams of harvesting its rich fields of patronage and building up their new organization. Others were reformers determined to implement their program from the State level. All were convinced that as masters of the state they had the legal authority to become masters of the city.

A series of recent decisions by the New York Court of Appeals had put paid to Manhattan’s lingering claims to special status as a municipal corporation, with independent powers derived from colonial-era charters. City property, the judges ruled, was held entirely in trust for the public. The corporation as such had no inherent authority over even the city’s streets, and the state legislature could interfere at will in its affairs. The government of New York City—like that of even the smallest upstate village—existed only to the extent the state granted it governmental authority.

In ruling thus, the judges completed a legal revolution, begun back in the 1780s, that distinguished between public and private corporations. The two had long been considered kin in both having rights—rooted in charters—which in varying degree insulated them from central authorities. Now only private corporations (as fictive persons) were deemed to have rights against the state and immunities from legislative intervention. Municipal “corporations,” their name to the contrary notwithstanding, were declared mere agencies of the state, with no legal autonomy whatever. In 1857 the legislature underscored its awareness of the new legal situation by declaring itself free to intervene at will in the affairs of the municipality—and promptly proceeding to do so.

The legislature changed the city charter yet again—although this time, unlike earlier revisions, it was not submitted to the people of New York for their approval. Again, the Common Council was stripped of power, this time over finances, with authority to administer the city’s real estate, audit its accounts, oversee its disbursements, and collect its taxes being transferred to the comptroller. Again, ostensibly, the mayoralty was strengthened, this time by being given the power to appoint and remove most heads of departments, with consent of the aldermen. But in fact the legislature took dead aim at the office and its current occupant. Mayor Wood was required to stand for reelection in December 1857—his term slashed in half while the comptroller, a Republican, was allowed to finish out his second year. Then the legislature erected a series of state agencies to administer city affairs that were utterly free from control by municipal representatives (and the immigrant masses to whom they owed allegiance). When added to the already existing state boards that oversaw the almshouse, the asylums, and the Croton Aqueduct, these new institutions gave Albany control over three-fourths of New York City’s budget.

The new agencies spanned a wide spectrum of public affairs. The New York Harbor Commission was given control of the port, including authority to block further encroachments into the rivers by defining a permanent bulkhead line. Command of the building of the city’s new park, together with its enormous patronage opportunities, was handed over to a Board of Commissioners of the Central Park, a self-perpetuating entity appointed by the state legislature. Another body was given the right to administer construction of a proposed new City Hall.

At the urging of environmentalists, the legislators expanded the purview of the Croton Aqueduct Department beyond its existing responsibility for water supply and sewerage to include street pavements, pumps, and privy vaults, but in leaving intact the Common Council’s cojurisdiction over public works, they thwarted the department’s ability to impose systemic reforms. In Brooklyn, however, they created a Board of Sewer Commissioners and empowered it “to devise and carry into effect a plan of drainage and sewerage for the whole city, upon a regular system,” which it did. In addition, a local Board of Water Commissioners oversaw establishment during 1856-58 of a system that tapped streams and ponds on the southern shore of Long Island (leased or purchased by the City of Brooklyn), ran the water through a brick conduit (along today’s Conduit Avenue), and pumped it up the glacial moraine (at today’s Force Tube Avenue) into Ridgewood Reservoir (in today’s Highland Park) from which it flowed down to the city in iron mains. A secondary distributing reservoir atop the higher Prospect Hill (within today’s Mount Prospect Park near Flatbush Avenue and Eastern Parkway) supplied those parts of Brooklyn above the level of Ridgewood.

State Republicans were able to make as much headway as they did because state Democrats were divided into contending factions, and those who feared Wood’s growing power—he was being talked of as the next Democratic candidate for governor—were prepared to back Republican wing-clippers. In the city itself, many Tammanyites, fearing that Wood’s ascension would help immigrants expand their base in the machine, considered him a greater threat than the Republicans, who were weak in the metropolis itself.

Among Wood’s Democratic opponents was William Tweed, who had returned from two unhappy and undistinguished years in the House of Representatives, a largely forgotten man. Determined to bid for power by striking at the existing leader, Tweed was given his chance by the Republicans, who in their eagerness to curb metropolitan power unwittingly provided him with a base of operations. In yet another reform, legislators enhanced the power of the New York County Board of Supervisors, created as a check on city government, by giving it authority to audit county expenditures, supervise public works, oversee taxation and the various city departments, and appoint the inspectors of elections. In an effort to underline the purity of their intentions, they incautiously made the twelve-person board (six elected, six appointed by the mayor) bipartisan. Among those who climbed on board in 1857 was William Tweed. Within a year he had formed a “ring,” a combination with other equally unscrupulous supervisors, which began levying a systematic 15 percent tribute on all vendors who furnished the county with supplies. Tweed also used his new status to dramatically enhance his standing among ward leaders and to promote friends to office, including, by 1858, George Barnard (recorder), Peter Sweeny (district attorney), and Richard Connolly (county clerk).

In the meantime, Republican reformers, unaware of what they had spawned, decided to press on with their campaign against the miscreant metropolis. Utterly heedless of the possible impact on even sympathetic Democrats, they proceeded to pass two acts, on April 15 and 16, 1857, that drew a moral line and provided the muscle to make the city toe it.

Their new Liquor Excise Law was an attempt to circumvent judicial decisions that had stymied their 1855 effort at straight-out prohibition of alcohol. The act required saloonkeepers to obtain a license. Applicants had to submit, to a Board of Excise Commissioners, vouchers attesting to their good moral character signed by thirty resident freeholders (those with absolute ownership of an estate), post a bond, and provide boarding facilities and stables. The Herald surmised such requirements would force out of business thirteen of every fourteen saloons in the city, and probably ninety-nine of every hundred in the lower wards where few freeholders lived. The law also banned the sale of liquor on Sunday or election days, further foreclosing working-class access to spirits, and—in a quasi-feminist intervention into hitherto sacrosanct family life—provided that on a wife’s complaint, a husband could be put on a list of known drunkards to be distributed to all liquor dealers.

Republicans, perfectly aware that if enforcement was left to New York’s current municipal leadership (i.e., Mayor Wood) it would swiftly become a dead letter, passed a complementary piece of legislation, the Metropolitan Police Act, which shifted effective control of the force from the (Democratic) mayor to a Metropolitan Police Commission controlled by (chiefly Republican) state appointees. The new law also dropped the requirement that officers serve in the ward where they resided, seeking (as had London) to sever the connections between cops and communities. The new commissioners—whose domain included Kings, Richmond, and Westchester counties as well as Manhattan—were given tremendous powers. Not only had they authority to enforce the Sunday closing laws, but they had complete control over the election machinery of New York and Brooklyn.

This legislative one-two punch produced instant furor. In May 1857 a Democratic mass meeting in City Hall Park attacked the Republican “principle of governing by boards” as despotic. Just the right word, thought the Irish News, which denounced the Republican laws as “specimens of despotic legislation which Louis Napoleon, with his legion of spies, a garroted press and an army of mercenary bayonets at his back, would hardly attempt in Paris.”

Democrats were not alone in their outrage. Harper’s said the laws resembled those imposed “on revolted districts or conquered places.” The Herald evoked city-versuscountry sentiments when it branded the upstate legislators as “archaeological curiosities” who “daren’t trust themselves alone with a loaded pistol, or a gin bottle, or a pretty girl. . . without a good stout law to protect them and keep them in bounds.”

But it was Mayor Wood who emerged as municipal champion. Blasting the excise law as “another of the encroachments upon individual rights for which the dominant party are so much distinguished,” he called for resistance to an insolent state centralism that would make of New York a “subjugated city” and plunge its citizens into a “feeble state of vassalage.” Claiming the laws violated home rule rights guaranteed by the Dongan and Montgomerie charters, Wood ordered all policemen to reject die authority of the new metropolitan commissioners, at least while he instituted legal proceedings to get the law declared unconstitutional. Those who defied him he fired.

To bolster his position, Wood got the Common Council to establish a separate Municipal Police force, composed of all pre-1857 officers, under direct mayoral control. There were now two official departments, and between late May and mid June 1857 policemen of the various wards were forced to choose up sides. In the end about eight hundred cops and fifteen captains stayed with Wood’s Municipals and three hundred cops and seven captains opted for the Metropolitans (splitting more or less on ethnic lines). Each of the rival forces then proceeded to fill up its vacancies (again ethnically, the Mets tending to appoint Anglo-Americans, the Munis leaning toward the foreign born).

Chaos ensued. Criminals had a high old time. Arrested by one force, they were rescued by the other. Rival cops tussled over possession of station houses. The opera bouffe climax came in mid-June when Metropolitan police captain George W. Walling attempted to deliver a warrant for the mayor’s arrest, only to be tossed out by a group of Municipals. Armed with a second warrant, a much larger force of Metropolitans marched against City Hall. Awaiting them were a massed body of Municipals, supplemented by a large crowd (characterized by George Templeton Strong as a “miscellaneous assortment of suckers, soaplocks, Irishmen, and plug uglies officiating in a guerrilla capacity”). Together, the mayor’s supporters began clubbing and punching the outnumbered Metropolitans away from the seat of government. “The scene was a terrible one,” a Times reporter wrote; “blows upon naked heads fell thick and fast, and men rolled helpless down the steps, to be leaped upon and beaten till life seemed extinct.” The Metropolitans gained the day after the Seventh Regiment came to its rescue, and the warrant was served on Wood. This setback for the mayor was followed by another: on July 2 the Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the state law. Wood knuckled under and disbanded the Municipals late in the afternoon of July 3, leaving the Metropolitans in possession of the field.

The ultrareformers had triumphed over Wood, but it proved to be a shaky victory. Exactly how shaky became clear the very next day.

July 4, 1857, promised, like most Independence Days, to be given over to massive parades, democratic rhetoric, hard drinking, and street brawls. The unenviable task of maintaining a minimal degree of order and decorum was now to be shouldered entirely by the Metropolitans. Their ranks were notably untested. The victorious department refused to hire those who had backed the losing side, choosing instead to swear in a host of special officers, with little or no experience, to flesh out their ranks. All in all, no more than a hundred had had even a month’s experience.

When a small party of Mets patrolling the Chatham Square area in the predawn hours suddenly found themselves under attack by a crowd of young men and boys, they broke and ran. One sought shelter in the saloon headquarters, at 40 Bowery, of the Bowery Boys, a nativist gang, who succeeded in repelling the assailants. At this point, the Dead Rabbits—the Irish Sixth Ward gang whose members were known as ardent Wood supporters—opened up another front on Bayard Street, between Mulberry and Elizabeth; together with the neighborhood’s Irish inhabitants, they attacked a group of thirty Metropolitans. Once again, the on-the-job trainees had to be rescued by a phalanx of two hundred Bowery Boys. While the policemen straggled away from the scene, the gangs and their supporters escalated their encounter. Barricades went up, assembled out of carts, barrels, lumber; brickbats flew (women, it was said, gathered and broke up stones and carried them to their menfolk on the front lines or atop the tenement roofs); then the guns came out. The battle raged for hours, drawing thousands to the scene, and was ended only by the exhaustion of the participants. Twelve died outright or soon thereafter, and thirty-seven were injured. It was the worst riot since Astor Place back in 1849.

The next day, Sunday, violence flared again, but this time it was put down by the

The Dead Rabbits barricade on Bayard Street, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 18, 1857. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

National Guard (with Metropolitans placed at the head of the regiments). The streets were swept clean. The Sunday closing laws were enforced.

On Thursday, July 9, fifteen hundred turned out for a meeting at Hamilton Square that had been called to consider “effecting a division of the state, by organizing a new one from the five southern counties.” The mayor showed up but told the crowd it must obey the legislature’s laws. (As a potential gubernatorial candidate, secession of city from state was not, at this point, in his interest.) Passions lowered to a simmer.

They boiled over again the following Sunday, July 12, this time in the heart of Kleindeutschland, at Avenue A and 4th Street. Several thousand Germans taunted the Metropolitans and met their efforts to close saloons and clear streets with clubs and brickbats. Reinforcements—three regiments and most of the police force, massed five abreast—drove them back; a blacksmith was killed in the process. The next day a funeral procession, ten thousand strong, marched up Broadway under a banner reading OFFER DER METROPOLITAN-POUZEI (victim of the Metropolitan Police), accompanied by a dirge-playing band. A mass meeting denounced the tyrannical laws.

Order was restored. But no one, least of all the police, imagined that popular hatred of the new laws, and their defenders, had been other than driven underground for the moment. The superintendent of the Metropolitans recommended that ten officers in each ward be armed with revolvers—“for the suppression of riots.” Ominously, the state decided to build a new armory at 35th Street and Seventh Avenue, more than a mile closer to City Hall (and the Sixth Ward) than the existing one.

It seemed as if long-accumulating tensions were coming to a head, as if a cultural crossroads had been reached. On one side was the growing immigrant working class, with its own culture, its own politics. On the other side was a wealthy and anxious bourgeoisie, trying not very successfully to impose its vision of domestic and civic relations on those below.

For a time, it had looked as if Mayor Wood might be able to mediate this clash, but the upstate victory of the ultrareformers had put him in an impossible position. Either he enforced the liquor and police laws and lost his immigrant constituency, or he rejected reform and lost the fragile support of the rich and powerful. Faced with that choice he opted to secure his political base. In this he succeeded; in October, Wood, an idol to Democratic voters, gained Tammany’s renomination for the mayoral race. But the summer’s events had cost him dearly. Many reformers now turned away from him. Still, Wood might have been able to salvage the situation; he retained important upper-class support. But at just this point, the city was rocked by an economic earthquake that made glaringly apparent just how deep the fissures in civic life had become, just how wide a gap now yawned between the contending cultures, and just how unbridgeable they were by even the most heroic of political efforts.