In 2017, Amazon acquired the grocery store chain Whole Foods for $13.7 billion. How does this acquisition change the way you see both companies?

AP Photo/Gado Images

Key Idea: Historically, the mass media industries have followed a life cycle pattern of development (innovation, penetration, peak, decline, and adaptation stages), but now the most powerful force shaping its current nature is convergence.

· The Evolution Pattern

o Stages of Evolution

§ Innovation Stage

§ Penetration Stage

§ Peak Stage

§ Decline Stage

§ Adaptation Stage

o Comparisons across Mass Media

· Revolution Pattern of Development

o The Analog Media

§ Channel

§ Decision Making

§ Messages

o The Digital Media

§ Channel

§ Decision Making

§ Messages

§ Range of Experiences

o Convergence

· Profile of Mass Media Workforce

· Summary

· Further Reading

· Keeping Up to Date

· Exercises

Heather was determined to do well and earn a high grade in a course titled “Development of the Mass Media.” She had bought the textbook, which included a dozen chapters, each one on a different type of mass medium. She had read each chapter carefully and highlighted the important facts in green. Now, as she prepared to study for a major test, she noticed that almost every word on every page was green. She felt frustrated and thought, “How am I ever going to learn all this material? It’s too much. There are a million tiny facts. There is no way I can memorize all these facts.”

It is likely that many of you have felt like Heather when you were confronted with a subject that is composed of a great number of facts. When you first look at the mass media, there appear to be many components—books, magazines, newspapers, audio recordings, films, radio, broadcast television, cable television, and the proliferation of platforms brought about by computers, the internet, and mobile devices. Each of these components has its own collection of detail—dates, historical occurrences, inventors, entrepreneurs who created businesses, complicated charts of who owns what, and tons of financial data.

When I first started writing about this topic, I too was overwhelmed. But then I started to see patterns. These patterns helped me organize all the detail and make sense of this complex and ever-changing phenomenon of the mass media. In this chapter, I present two of the most useful patterns to help you understand what all these industries have in common and appreciate their uniqueness. The first of these patterns is a set of stages that each medium has followed as it has developed and changed over time. I call this the evolution pattern. The second of these is a revolution pattern that explains the enormous changes that have taken place across all the mass media industries over the last several decades.

In this chapter, I will focus your attention on these patterns. Once you understand these patterns, then you can add detail in order to elaborate your understanding of them. Many of those details about the media industries are provided for you in Appendix A (see Media Literacy, 10th edition on http://sagepub.com, then use the SAGE Edge link), and if you want even more details, then you can continue acquiring facts by looking at the suggestions for Further Reading and Keeping Up to Date at the end of this chapter.

THE EVOLUTION PATTERN

Some of the mass media industries are relatively old and have been around for more than two centuries (e.g., books, newspapers, and magazines) while others are relatively young (e.g., cable television and especially the internet). Although each medium has been shaped by different historical influences, technologies, regulations, and audience needs, all of these media have followed a similar pattern in the way they have evolved over time. This evolution is composed of stages in a life cycle pattern of innovation (or birth), penetration (or growth), peak (maturity), decline, and adaptation. Let’s examine each of these five stages.

Stages of Evolution

Innovation Stage

Each of the mass media industries began as an innovation. The innovation stage of a medium’s development is characterized by a technological innovation that makes a channel for transmitting information possible. For example, there would be no film industry if someone had not invented the motion picture camera and projector. However, technology by itself is not enough to create a mass medium. A mass medium is more than an invention; there have been many technological innovations for the dissemination of information that have failed. So, the innovation stage is also characterized by marketing innovations in addition to technological innovations. This means that someone had to create a business that would use the technology in a way that was successful in attracting audiences and conditioning those audience members for repeated exposures.

A successful marketing innovation begins with an entrepreneur recognizing a need in the population and then using a new technology to satisfy that need in such a way that people begin recognizing the value of the new medium and how it can help them. To do this, the entrepreneur must have a mass-like orientation; that is, they must exploit a technological channel’s potential to attract particular audiences and then continue to use that channel to condition those audiences for repeat exposures. For example, in the early 1900s, after the motion picture camera and projector were invented, some entrepreneurs turned their living rooms into theaters and began charging people to watch the movies they showed in their homes. These entrepreneurs found that there was a market for this kind of entertainment, so they took steps to grow a business by renting out storefronts to accommodate larger audiences, then they rented concert theaters, and then they built their own theaters that were primarily for the showing of films. This growing number of large theaters not only met the demand for movies but also served to increase the demand. This increasing demand stimulated other entrepreneurs to create film production companies to make and distribute more and more films to the growing number of theaters. Without all these entrepreneurs who recognized a public need and marketed their services to grow that need into a habit, the technology of the motion picture camera and projector would never have developed beyond a curious invention.

Compare & Contrast Technological Innovations and Marketing Innovations

Compare: Technological innovations and marketing innovations are the same in the following ways:

· Both involve the creation of new ways of crafting messages and disseminating them to target populations.

· Both are required characteristics of the innovation stage in the development of the mass media industries.

Contrast: Technological innovations and marketing innovations are different in the following ways:

· Technological innovations are engineering-type improvements whereas marketing innovations are business-type improvements that have created new ways to capture, store, and transmit information in print, graphic, photographic, audio, and video formats.

· Technological innovations are typically inventions of media hardware as means of recording and disseminating messages whereas marketing innovations are strategic-type inventions that have created new ways to identify audiences and their needs, attract their attention, and present messages in a way that holds their attention and conditions those audiences for repeated exposures.

Penetration Stage

Once an innovation has created a new media channel, that channel needs to appeal to a very large, heterogeneous population if it is to be effective as a mass medium. This stage is called penetration because it highlights the increasing acceptance of a medium as it grows its audience from a few innovators by attracting early adopters to the majority of a population and finally to everyone. The rate of penetration is determined by how fast the public regards the new medium as being able to satisfy their existing needs better than any alternative.

Often, the public has a need that is already being satisfied by the existing media, but a new medium comes along that can satisfy those needs better in some way. For example, in the 1940s, people were satisfying their need for entertainment with radio and with films. When broadcast television was introduced, the public shifted its time away from radio and toward television because it offered pictures in addition to sound. Thus, television served the public’s need for entertainment better than radio. Television was also better at satisfying many people’s need for entertainment compared to film because television brought many hours of entertainment into a person’s home each and every day, so there was no need to leave the house, get a babysitter, find a parking place, or buy a ticket. Television was much more convenient.

As each medium grows, it is influenced by factors that shape its growth. These factors include the public’s need and desire for the medium, additional innovations that change the appeal of other competing media, political and regulatory constraints, and the economic demands of the private enterprises that own and operate the mass media.

Peak Stage

The peak stage is reached when the medium commands the most attention from the public and generates the most revenue compared to other media. This usually happens when the medium has achieved maximum penetration; that is, a very high percentage of people have accepted a medium and the medium cannot grow in penetration any more. Of course, it can continue to absorb a greater proportion of an audience member’s time and money. For example, broadcast television reached a peak in the 1960s after taking audiences away from radio and film. Broadcast television also had taken national advertisers away from magazines, newspapers, and radio. Until the 1990s, broadcast television remained at a peak as the most dominant mass medium because people were spending more time with broadcast television every day compared to any other medium. Also, most people regarded broadcast television as their primary (and often only) source of entertainment and news.

When a medium is at its peak, it is usually the dominant medium; that is, it is the most important medium to the greatest number of people. This can be seen in terms of how much money the industry generates and how much time people spend with that medium (see Table 5.1). Notice that radio is in second place with the amount of time that people spend with it per year. Does this mean that radio should be considered the second most dominant medium? The answer is no, for several reasons. First, although people spend a lot of time with their radios on, they are using the medium for background noise; that is, they are not really paying much attention to those messages. When radio was at its peak in the 1920s and 1930s, its programming commanded listeners’ full attention. That programming included a wide range of genres that are now seen on television. People would listen to soap operas, detective shows, game shows, and comedies. But now, most of radio listening is background music. While listening to this music, people are typically exposing themselves to other media (such as reading books, magazines, and newspapers) or they are doing something else (such as talking on the phone, jogging, or working) that requires more attention. Even though the radio is on for so many hours in the lives of so many people, it does not hold people’s full attention for very long.

Table 5.1

Time figures are hours and minutes per person per day on average.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau (2009). The 2009 Statistical Abstract: The National Data Book. Washington DC: Department of Commerce, Table 1089; eMarketer 2017, May 1

Second, radio does not generate as much revenue as other media. Does this mean people do not spend money on these media? Of course not. It means that these media do not get any income directly from the consumer. People must buy receivers, but that money goes to Best Buy, Walmart, or wherever people buy their receivers. Broadcast radio and television get almost all of their revenue from advertising, which comes from consumers but only indirectly. Table 5.1 includes only direct revenues from consumers to the media businesses themselves.

Decline Stage

Eventually, a medium at its peak will be challenged by a newer medium and go into a decline. In the decline stage, the medium is characterized by a loss of audience acceptance and therefore by a loss in revenues. A decline in audience size results not from a decline in the need for a particular kind of message but by those message needs being satisfied better by a competing medium that is growing in penetration and moving toward its own peak. For example, broadcast television experienced a decline in audiences and advertisers throughout the 1990s with the increase in cable channels. People were reducing the amount of time they were watching television shows designed to appeal to everyone, which was how broadcast television shows were designed, and shifted their television viewing time into messages that appealed more strongly to niche audiences, which is how cable television messages were designed. Cable television provided more messages for people interested in news (CNN and FOXNews), sports (ESPN), movies (TCM), comedy (Comedy Central), and music (MTV and VH1). Because cable television offered a wide range of content choices to people in just about every niche of interest, cable grew to a peak by taking audiences and advertisers away from broadcast television. Now in the new millennium, cable has been experiencing declining audiences as people shift to the digital media to provide them with an even wider variety of entertainment and information.

Internet music providers, such as iTunes and Spotify, appeal to the needs of niche audiences by offering user-created playlists and personalized stations based on individual preferences.

iStock.com/Wachiwit

Adaptation Stage

A medium enters the adaptation stage of development when it begins to redefine its position in the media marketplace. Repositioning is achieved by identifying a new set of audience needs that the adapting medium can meet because the old audience needs it used to fulfill are now better met by another medium. For example, after radio lost its audience to television, radio adapted by doing three things. First, it stopped competing directly with television by eliminating its general entertainment programs such as soap operas, situation comedies, and mystery dramas. Instead, radio shifted to music formats in which disk jockeys would play popular songs one after another. Second, radio abandoned its strategy of trying to appeal to a general audience and instead segmented the market according to musical tastes; each station aimed its programming at the people in one of those niches. Each radio market offered a range of music choices with a top 40 station, a rhythm and blues station, a jazz station, an album-oriented rock station, a golden oldies station, a country and western station, a classical music station, and so forth—each appealing to a different niche of listeners. Third, it realized that with the invention of the transistor radio in the 1950s, it could be portable (whereas television could not at the time). So, radio developed playlists that formed a kind of background mood-shaping experience as people drove in their cars, laid out on beaches, and talked on the phone.

For the past several decades, broadcast television has been in decline as it fights off challenges first by cable television and now by the digital media. Broadcast television is trying to adapt, much as radio did in the 1950s by trying to be more mobile and programming to niche audiences.

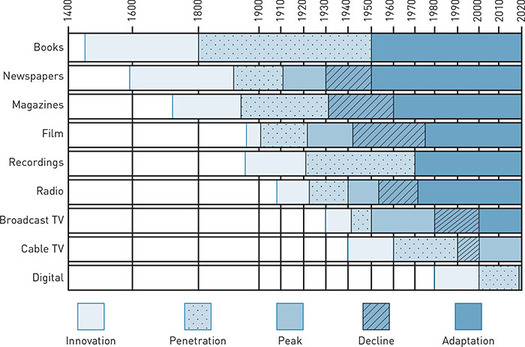

Comparisons across Mass Media

Now let’s look at the big picture across the media industries (see Figure 5.1). The print media of books, newspapers, and magazines are the oldest, with each of them moving out of their innovation stage more than a century ago. Digital, which is the newest mass medium, has quickly moved from innovation to penetration and is entering a peak stage; this fast growth has put all of the other mass media into an adaptation stage in which they are scrambling to find ways to compete with the digital media in order to survive.

Description

Description

Figure 5.1 Life Cycle Patterns

Although the life cycle pattern is a good template for showing patterns, it is not perfect. For example, notice that several of the media (books, magazines, and recordings) never reached a peak. This does not mean that those media are not important or successful; it only means that those media never achieved dominance as the most important mass medium at a given time.

We are currently in a very dynamic and interesting time with the development of the mass media. The newer technologies that can be grouped under the title of “digital” are changing the way audiences access media messages by giving them much more control and variety. Take film, for example. By 2010, Americans were spending almost twice the money on home viewing of movies (on-demand videos, digital downloads, and DVDs) than going to theaters (“Unkind Unwind,” 2011), and by 2014, Americans spent more on movie streaming and downloads (Netflix, Amazon Instant Video, etc.) than they did buying tickets at movie theaters (Rigby, 2014). When people’s film choices are limited to commercial theaters, they have only about a dozen choices at any given time. Also, they must physically be at the theater when the film starts and sit there for the entire running of the film unless they want to miss some of it. However, when people watch a film through their cable provider or especially from a website, they have a virtually unlimited range of choices and they can watch the film whenever they want and interrupt whenever they want.

Accessing news stories is much faster and up to date with websites than when waiting for printed newspapers or magazines to be delivered. Access to books and recordings is faster when downloading them to handheld devices than driving to a brick-and-mortar store. The newer media are growing fast and moving quickly through the penetration stage. They are putting growing pressure on the older media, forcing them to continue adapting.

It appears that digital media are now entering the peak stage. The time spent with digital media has grown dramatically over the last decade (see Table 5.1). Notice that time spent with television, radio, and print has declined a bit while the time spent with the internet has increased by more than three hours per day! Television is credited with increasing the American public’s appetite for entertainment. The amount of time spent viewing television steadily increased since television was first introduced until the early 2000s, when internet use started to grow dramatically, as the internet could provide all the entertainment and news that television could plus satisfy an even broader range of needs. In 2009, people spent an average of 6:08 hours per day viewing live television (broadcast and cable) and an average of 48 additional minutes per day with the internet. By 2017, television viewing had declined to 2:44 hours per day and internet usage had increased to 2:37 hours per day (Dunn, 2017). This pattern illustrates two ideas. First, the internet has been taking time away from television, which indicates that the internet is better satisfying the needs that television viewing used to. Second, the rise of the internet illustrates that it is growing the needs of the population because the time spent with both of these media has now grown to over 13 hours per day in the United States (Dolliver, 2020).

As digital media are peaking, all the traditional media are in decline. In the decade from 2007 to 2017, time spent with the traditional media of television, radio, and print has declined from 7:29 to 5:51, while time spent with digital media increased from 2:18 to 5:50 (see Table 5.1). In 2007, 76% of our exposure time was with traditional media, and that eroded to 50% a decade later—even though our overall time spent with the media increased 19% during that period. This is a significant shift that can be explained by the digital media that allow us to satisfy all the needs that traditional media have been (plus more) and to satisfy these needs quickly and anywhere with our mobile devices. The typical smartphone, which now has more computing power than Apollo 11 had when it landed a man on the moon (Gibbs, 2012), allows users to make phone calls, send texts, play music, read books, take pictures, and record video. With the use of apps, smartphones can access the internet, play games, trade stocks, follow traffic patterns in real time, and even pay for purchases at brick-and-mortar stores. In the United States, 72.2% of all people own a smartphone (O’Dea, 2020) and 46% of all smartphone users say that it is something they could not live without (Raine & Perrin, 2017) and one-quarter of all users say they use their phone to stay online almost constantly (Perrin & Jiang, 2018).

At this point, let’s see if you can use the information you have learned thus far in this chapter about the patterns of development of the mass media industries. Exercise 5.1 gives you a chance to apply your knowledge about how the mass media industries sprang into being through technological and marketing innovations and grew larger and more powerful to a peak stage. Think about what the peak stage really means to a media industry and how the industry at a peak affects all the other media industries. This exercise has no right or wrong answers because it asks you to speculate what will happen with the digital medium five and twenty years into the future. Think outside the box of the present time and have some fun predicting the future!

REVOLUTION PATTERN OF DEVELOPMENT

The newest mass medium goes by many different labels—computer, internet, nontraditional, and newer media to name a few. I will refer to it as digital because its most fundamental characteristic is the way messages are stored and transmitted—by digital code. Up until the digitization of messages, each of the mass media used an analog form of capturing information, storing it, and transmitting it. Therefore, I will refer to this set of the mass media (print [books, magazines, and newspapers], audio recordings, film, radio, broadcast television, and cable television) as analog media.

Although the digital medium is fairly new, it appears to follow the life cycle pattern with its innovation stage, penetration stage, and quick ascendency into a peak stage. This rapid growth appears to be more of a revolution than an evolution. It is a revolution not only because of the speed of its growth; other media—particularly radio and broadcast television—also exhibited rapid growth from innovation to peak. The digital media have created a revolution for two additional reasons. First, the rapid rise of the digital media is attributed not only to the way digital platforms can serve the existing needs of the population better than the analog media can but also because those platforms have greatly expanded the variety of needs that they can serve. The digital media offer a far greater range of information and entertainment than the analog media, and they also offer ways for users to connect with one another and compete with one another that the analog media cannot. A second reason to consider the rise of the digital media as being revolutionary is because the digital medium has exerted so much pressure on all of the analog to adapt that those adaptations are resulting in a convergence of all media; that is, the analog media are changing so much that their emulation of the digital medium is resulting in the analog media losing their distinctiveness.

The Analog Media

Since the invention of moveable type and the printing press almost six centuries ago, there has been a series of innovations in preserving messages and transmitting those messages quickly and widely. These channels, which are sometimes called traditional or old media, include print channels (books, newspapers, and magazines), audio recordings, film, broadcast (radio and television), and cable television. While the most recognizable characteristic of analog media is that their messages are channel bound, they also differ in terms of how decisions are made regarding what messages get produced and distributed and the nature of those messages (see Table 5.2).

Table 5.2

Channel

The most primary characteristic of analog media is that their messages are channel bound. This means that each of the analog media uses a different kind of technology to capture information, store it, and transmit it to audiences. For example, the channel of audio recording requires a certain kind of microphone that is sensitive to sound waves and translates them into electrical impulses. Those electrical impulses were first stored on vinyl discs by carving fluctuations into the groove that ran in a circular pattern on the surface of the vinyl disc. A needle was placed into the groove and the disc rotated so the needle could progress along the groove, picking up the fluctuations and translating them back into electrical impulses that traveled to a speaker where those electrical impulses were then translated into sound waves so listeners could hear the recording. In contrast, the channel of broadcast television relies on video cameras to capture moving images and imprint that information on electromagnetic waves that are sent wirelessly. When a television receiver captures these electromagnetic waves, it is able to translate the information on those waves into electrical impulses that were sent to a cathode ray tube that fired a stream of ions to a screen that was painted with pixels that glowed when ions hit it. The pattern of glowing pixels created images that appeared to move on the screen. As you can see from these two examples, each analog medium relies on a very different set of technologies to capture, store, and transmit its messages. Thus, it requires considerable technology to translate a message that was captured in one analog medium into a different analog medium.

Analog coding is the recording, storage, and retrieval of information that relies on the physical properties of a medium. Print information is stored as ink marks on paper. Sound recording information was stored as fluctuations within the grooves in vinyl disks. As a vinyl disk revolved on a turntable, a needle was dragged through the groove and picked up the tiny fluctuations pressed into the walls of that groove and translated those fluctuations into electrical impulses that were sent to an amplifier and then to a speaker where those impulses were translated into movements in the speaker, which sent out waves of compressed air to human ears. In the 1970s, recording companies began shifting from vinyl disks to magnetic tapes but the analog system of coding was still used.

Decision Making

The analog media are also characterized by centralized decision making. That is, they are controlled by hierarchically structured industries in which experts at the top of those hierarchies make decisions about the creation and distribution of messages. This means that the creators of analog media messages must guess what audiences will want, then create their messages by assembling elements they think will appeal to those potential audience members, and then send their messages out, hoping that those messages will attract relatively large numbers of users. Of course, even with analog media, there is feedback but that feedback is seldom immediate; it takes a relatively long time to get this feedback—days or weeks rather than seconds or minutes. For example, feedback in book production is in the form of weekly sales data and reviews of those books published in magazines and newspapers. Feedback on audience sizes for prime-time television shows is provided the next day by Nielsen overnight reports. The feedback is not specific; producers of analog media messages do not get detailed feedback about why people exposed themselves to particular messages or their reactions to the particular elements they liked or disliked in those messages.

Messages

The analog media businesses produce standardized messages that they hope will attract large numbers of people. These message units (e.g., a daily newspaper, a Hollywood movie, an album of 12 song recordings, a television series) are produced by a team of professionals who have the skills to create a product that achieves high production value. These professionals create messages by adding characteristics that they believe will appeal to a wider range of individuals thus increasing the probability that more consumers will expose themselves to their message. For example, a daily newspaper creates a product each day that includes a wide range of news stories (hard news, features, sports, recipes, horoscopes, comics, etc.) that it hopes will attract a large number of readers. While this is a good strategy for media businesses to use to increase the appeal of their messages, it also has a downside, which is that consumers must pay for the full bundle of messages when they may want access to only one message in the bundle. That is, people who want to read stories about local sports teams each day must pay for the entire newspaper although they only read the sports page. Likewise, subscribers to cable television services are presented with several bundles of channels, but they cannot break the bundles apart and subscribe to individual cable channels. The products that the analog media provide to audiences are units that contain a variety of elements that vary in interest to each audience member, but in order for an audience member to get access to that unit, they must pay for the entire bundle.

The Digital Media

Channel

With the digital media, there is great fluidity across technological channels. When information is captured—whether through a microphone, still image camera, video camera, or word processor—the information is translated into binary code that can be used by all digital media. That is, every element in a message is translated into either a 0 or a 1, and the message itself is expressed in a long string of those zeros and ones in order to capture all the elements in a message. This binary code is the standard language of computers and the internet, so any message that has been digitized can easily be transmitted across a very wide range of digital channels and platforms.

Digital recording of information offers several major advantages over analog recording. Perhaps the biggest advantage is that digital code is standard and can be read by any medium while the analog code is different for each medium. This standard code allows for easy making of copies of a message and accessing those copies on many different kinds of platforms. Another big advantage is that the digital code can be compressed so that it is possible to store a huge amount of information in a very small space. For example, you can store thousands of songs, texts, books, and videos on a small handheld device such as your smartphone. Because of these advantages, all of the mass media have been switching over from analog to digital means of recording, storing, transmitting, and retrieving their messages.

All the devices we think about as being digital media rely on computers to receive and present messages (Balbi & Magaudda, 2018).

The digitization of just about everything—documents, news, music, photos, video, maps, personal updates, social networks, requests for information and responses to those requests, data from all kinds of sensors, and so on—is one of the most important phenomena of recent years. (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014, p. 66)

This is why the computer has been called the mother of all digital devices: The computer requires the use of a uniform digital code so that information can be shared across all kinds of computers.

While the computer is essential to the digitization of messages, the internet has become essential to the distribution of those digitized messages. The internet is a worldwide network of circuits and packets of digitized data that connect countless billions of computerized devices and, thus, the people who use these devices (Blum, 2013). The internet has been called a network of networks because it makes it possible for an incredibly diverse range of networks to interact easily with one another by using shared protocols that link up different hardware and software (Balbi & Magaudda, 2018).

The digitization of messages and the use of the internet in sharing those digital messages has made it possible for the widespread use of mobile devices. These devices—particularly smartphones, tablets, and laptop computers—enable people to receive any kind of message (printed words, audio sounds, photographs, and video) wherever they can connect to the internet, which is virtually anywhere. This provides users of digital media with a degree of convenience that is far superior to what the analog media provide.

Decision Making

In contrast to the analog media, the digital media are organized horizontally rather than hierarchically. The interactive nature of platforms offered by the digital medium has forced decision makers to rely less on their presumed expertise and to be influenced much more by the emerging needs they perceive through interactions with potential audience members.

The interactive nature of the digital medium also allows every user to largely bypass authorities who used to function as gatekeepers and instead create any kind of content (e.g., creating texts, tweets, blog posts, email, photographs, recordings, and videos) and then distribute those messages widely by uploading content to internet platforms that make those messages instantly available to other people anywhere in the world.

Messages

The interactive nature of the digital medium has made mass customization available. Producers of digital messages—whether they be industry professionals or everyday people—continually interact with potential audience members in order to progressively refine their messages so as to maximize their appeal to particular niche audiences. Even after they have crafted their messages and distributed them, producers monitor audience reactions so that they can continue to produce messages that will satisfy specific audience needs. Producers pay a lot of attention to likes and ratings as well as engage in conversations with those users while they are being exposed to those messages. Thus, the digital media allow for feedback that is more immediate, more widespread, and more detailed than the type of feedback generated by the analog media.

Range of Experiences

Digital media offer an incredibly wide range of messages and experiences to users. Some of these are very popular and draw millions of users every day and some are more specialized and appeal to only a handful of users. A useful way to organize all these experiences is to categorize them by the general type of experience they provide to users—those experiences that are primarily competitive, those experiences that are primarily cooperative, and those experiences in which users are motivated primarily to acquire something they value.

Many interactive media platforms have been designed to attract users who want to compete against themselves, against a computer, or against one or many players. With the technology of computers, internet, and mobile devices, digital games became part of the mass media. These platforms offer users the opportunity to play simple games against a computer or to enter an exotic world where they can play complicated games with hundreds and even thousands of other players simultaneously around the globe. These experiences are examined in depth in Chapter 12.

Interactive media platforms that offer cooperative experiences have grown extremely popular. The most popular of these are what are called social networking sites (SNSs) such as Facebook (begun in 2004) and Twitter (begun in 2006). In 2008, 24% of the U.S. population were regular users of social media sites and this percentage steadily increased to more than 79% by 2019 (Clement, 2019). These experiences are examined in depth in Chapter 13.

People use interactive media platforms to acquire things of value directly from those platforms. These include information and entertainment experiences. People can also use internet platforms to shop and initiate purchases of physical goods. Of course, people can acquire these kinds of things from brick-and-mortar stores, but interactive media platforms are typically easier to use. These digital platforms that provide acquisition experiences are examined in some detail in Chapter 14.

We are now experiencing a significant change as people are shifting their attention and time toward the digital media. The reasons for this shift are that (a) the digital media satisfy many audience needs better than the analog media and (b) the digital media are able to satisfy audience needs that the analog media cannot. Therefore, it is likely that this shift will continue and that the power of the digital medium to exert influences on individuals and institutions will continue to increase.

Now the digital medium is moving into a peak led by a handful of companies that are less than several decades old but have already grown very large and powerful, such as Facebook (see Table 5.3) and YouTube (see Table 5.4).

Table 5.3

Sources: Angwin, 2009; CNN Library, 2018, March 22; Facebook, n.d.; Gramlich, 2018, April 10; Olivarez-Giles, 2011, June 14; The new tech bubble, 2011, May 14

Table 5.4

Sources: Chmielewski, 2011, May 31; Danny, 2018, April 26; Pingdom, 2011; YouTube, n.d.

Convergence

The key to understanding the nature of the mass media industries today is to realize how the influence of convergence has been so powerful over the past decade and will continue to be well into the future. In the most general sense, convergence simply means the moving together over time of things that were previously separated. With the media, convergence means the blending together of previously separate channels of communication so that the characteristics that have divided those channels into distinctly different media have been eroding. In this section, we’ll examine how three types of convergence—technological, marketing, and psychological—have been changing the nature of the mass media.

Technological convergence refers to how innovations about storing and transmitting information have brought about changes to the mass media industries. The key technological innovation that has been driving convergence is not the computer per se but the software code that runs computers. This software code is digital; that is, it is written, stored, and read as discrete, individual numbers that are arranged in sequences to communicate patterns. While computers and digital code have been around for more than half a century, it was not until about two decades ago that the media largely replaced analog coding with digital coding.

The movement from analog to digital—from audio cassettes to MP3s to smartphones, for example—has been key to technological convergence.

iStock.com/mattjeacock

While digitization of messages has been the major technological development leading to convergence, there have also been several other important technological developments that have helped this trend. One of these is the switching from copper wire to fiber optics in the sending of signals to televisions and computers. With the combination of compression of digitized information and fiber optics, both the amount of information and its speed have been increased thousands of times over the past few decades. With the availability of Wi-Fi and Bluetooth technologies, even greater amounts of information can move around at faster speeds. This has led to the availability of two-way communication. Computer users can both upload and download enormous files—such as huge software programs and videos—in a matter of seconds. People can engage in texting, instant messaging, and video conferences without wired connections.

Marketing convergence is a powerful influence that has changed the way media programmers regard audiences and how they develop their messages. In the past, media companies used to define themselves by channels—that is, newspapers saw themselves as a print medium only. However, technological changes have forced media businesses to move away from distinctions by channels of distribution and focus much more on the messages and the audiences. In the past, movie studios produced only films for theaters, magazine companies produced only print magazines, and recording companies produced only records. The channel limited their distribution and kept them in a box in which they competed only with other like companies. But now, media companies think outside the box (previously limited by their channel of transmission) and have broadened their marketing by thinking about all the ways they can distribute their messages across as many channels as possible.

With technological convergence, channels are much less important than audience needs and messages. Now mass media companies think first about the needs of different niche audiences, then develop messages to satisfy those audience needs. They translate that message into as many forms as possible to attract and hold that niche audience—film, television, websites, notebooks, cell phones, and so on. This procedure has two major advantages. One advantage is that a single message can generate many streams of revenue, so once the media company pays to have the message produced, it can collect revenues several times. The second advantage is that when the message appears in one channel, it stimulates audience members to expose themselves to the message in other channels. For example, people who read the Harry Potter books are stimulated to see the Harry Potter movies. They want to read about the actors in those movies in magazines, newspapers, and fan websites.

Director Sam Taylor-Johnson (far left) and author E. L. James (far right) accompany actors Jamie Dornan and Dakota Johnson, who helped bring the popular book series Fifty Shades of Grey to life on the big screen.

Dave J Hogan/Getty Images

This trend toward convergence also has changed the way media companies view audiences. In the past, the big media companies would try to attract the largest audiences possible. In order to do this, they would design their messages so they appealed to everyone without offending anyone with language or with certain themes that a part of the general audience might find distasteful. Thus, they adopted the programming principle of lowest common denominator (LCD). Programming has now shifted to what is called long tail marketing. To understand what a long tail is, think of a bell curve, which is referred to as a normal distribution by statisticians and college professors who grade on the curve. On any characteristic—height, weight, IQ, scores on tests, and so on—people are arranged in a distribution that ranges from lowest to highest, and most people cluster in the middle of the distribution. Let’s take height, for instance. Adult males can range from under four feet tall to over seven feet tall, which is a range of about 40 inches. Within this overall range, about two-thirds of adult males are clustered in the middle five inches (between 5 foot 7 inches and 6 feet), which forms the fat part of the curve. On either side of this fat part are fewer people who are either shorter or taller than the majority; these small areas on either side of the fat part are the tails. The tails are rather short on both sides of the fat part of the height distribution—there are almost no adult males who are taller than seven feet or shorter than four feet. However, when it comes to personal interests such as preferences for music or entertainment, the fat part of the distribution is not so fat; that is, there are fewer people who share the same preferences. For example, in order for a television series to be ranked in the top 10, it needs to attract only 3% of all U. S. viewers (Gillespie, 2020). Does this mean that people are watching less television? No, to the contrary: People are spending more time watching television, but they are spread out over hundreds of viewing options, each with a small audience. They are spread out over a very long tail of different preferences satisfied by many different viewing options. Long tail marketing refers to finding out what the special needs are for each of the many small niche audiences that form the long tail and developing content to attract that niche audience.

Long tail marketing is now a viable marketing strategy, given the trends discussed above. Huge media conglomerates have deep pockets and can afford to pay for the research necessary to discover these new niche interests and accept the risk of developing new messages. The internet allows for more experimentation and creativity. To illustrate, old-time brick-and-mortar bookstores had limited shelf space, so they had to be selective in choosing which books to stock. But Amazon.com is web-based, so it can market all books and thus has something to offer to every niche market—no matter how tiny—throughout the entire long tail of interests. This means that Amazon does not need to focus only on bestselling books (books ranked in the top 10 of sales). Amazon offers over 300,000 book titles for sale, but half of these titles sell less than 250 copies a year (Ranson, 2017). Therefore, it is more typical for Amazon.com to generate sales of one million copies by selling 250 copies each of 4,000 different books than by trying to sell one million copies of a single book. That is long tail marketing.

Convergence is not only a technological or marketing force; it also has profoundly changed the psychology of the audience (Jenkins, 2006). Psychological convergence refers to changes in people’s perceptions about barriers that previously existed that are now breaking down or totally eliminated due to recent changes in the media. These changes have served to help people see things in a different way and have provided them with tools to act on those changes in perception. One of these changes in perception concerns geography; that is, geographical barriers are no longer important. With email, instant messaging, social networking websites, and mobile phones, people can stay in close contact psychologically with friends and colleagues even when those people are not physically present. There has also been the breaking down of sociological barriers. With newer media platforms, a person can cross all those barriers to make contact with anyone, regardless of social class, occupation, ethnicity, or age. With the removal of these geographical and sociological barriers, people have redefined their social spheres.

Convergence has changed the way people think about the media and use them. That is, digitization has allowed people to access messages from various platforms and merge those into their own messages. The interactive features of many platforms have allowed users to bring together all kinds of previously unacquainted people into a single network of friends or professional colleagues. Thus, there is a convergence of people’s individual needs with the availability of ways to satisfy those needs. People are more active now and do not have to wait for media companies to recognize their needs; instead, they can assemble their own messages as their needs arise. People do not think of themselves only as consumers of the media but also as essential contributors.

PROFILE OF MASS MEDIA WORKFORCE

While the number of media businesses has remained relatively stable over the past decade, there have been significant changes across sectors within the overall media industry. Table 5.5 shows that the print sector has lost almost one-quarter of its businesses and that the broadcasting sector has also lost a large percentage of its businesses. During that same period of time, the number of businesses in the internet sector has more than doubled. This shift in businesses across media sectors illustrates the strong influence of the rise of the digital medium over the last decade.

Table 5.5

Source: Statistica (2018, May 27)

When we move beyond counting the number of businesses in the media sectors and try to count the number of people by media occupations, the counting gets challenging because traditional job titles have been losing their value as a way to identify what people do in occupations. For example, Table 5.6 shows that in 2011, there were 275,200 people categorized as working at advertising jobs, which has typically referred to people who work full time in either an advertising agency or an advertising department within a company doing traditional tasks of message design and placement in traditional media. While these types of jobs still exist, there are many other jobs that could be considered advertising but maybe not. For example, let’s say you own a local restaurant and hire several people to engage in text messaging with customers who have posted ratings of your restaurant on Yelp and other sites where customers rate businesses. While these employees spend their time designing and sending messages to your target audience in order to influence them to develop a more positive attitude about your restaurant and to eat there more often, should these employees be considered to be working in the advertising sector? Or should they be considered as being an author/writer or actor (if they are posing as fellow customers of your restaurant)? As another illustration of this problem with job classification, let’s say you start your own blog and each day upload the words you wrote, the pictures you shot, and the video you edited of you singing songs. Are you a producer, an editor, a sound engineer, an author, a photographer or a singer? Although you work at all of these jobs, should you be counted as being employed in each of these job categories? If so, should we also count all the millions of people who upload videos to YouTube as videographers, the tens of millions of people who post pictures on the web as photographers, and the hundreds of millions of people who email every day as writers? If we do count all these people as media workers, then most people would get counted multiple times, which would inflate the employment totals way beyond the total work force, and this would render the categorization of people into occupations as meaningless.

Table 5.6

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2011)

The most important thing to understand about employment in the media industries is that there are about two million people working full time in some traditional job of designing and distributing media messages (news, entertainment, and advertising) for an established media company. But almost everyone else in the total population is also continually designing and distributing their own messages through the media using the same skills (albeit at a much wider range of performance) as the full-time professionals. So, while these occupational numbers are useful in giving you some sense of the relative sizes of workforces, they need to be regarded with skepticism.

When looking at the total labor force in the United States, we can see a trend toward more and more women becoming employed outside the home. A report by the Boston Globe found that among the 151,436,000 people 16 years of age and older working in the United States, 46.9% were women (Rocheleau, 2017). When this total figure is broken down into occupational sectors, we can see a wide range of percentages of women across those sectors (see Table 5.7).

Table 5.7

Source: Adapted from Rocheleau (2017, March 7)

A popular profession within the media industries is journalism. In this journalistic community, there are about 67,000 reporters and correspondents, 23,000 writers and editors, and 67,000 radio and television announcers and newscasters. Most are male. The Women’s Media Center continually monitors the visibility of women in the media. In their 2017 report, they found that only about one-quarter of all broadcast news was being reported by women, 38.1% of print news was being reported by women, and 64.1% of online news was being reported by women (Women’s Media Center, 2017).

The figures presented in this section are general figures to give you a broad idea about the media workforce. These patterns might not hold in any one particular media industry or business. To check this out for yourself, complete Exercise 5.2.

SUMMARY

The development of the media industries generally moves from the innovation stage to penetration, peak, decline, and then adaptation. Remembering this pattern will help you understand how the media industries start, how they grow, and where they are today.

Historically, the mass media industries have been defined by the technological channels they have used to distribute their messages—book, newspaper, magazine, film, recording, radio, broadcast television, cable television, and computer. But over the past few decades, the mass media industries have undergone profound changes due to the forces of convergence—technological, marketing, and psychological. These forces of convergence have eroded the old channel distinctions and have shifted the focus away from the characteristics of distribution and onto the needs for media messages in distinct niches of audiences.

Further Reading

Drapes, M. (2009). Vault guide to the top media & entertainment employers. New York: Vault Inc. (137 pages, including appendices)

This is a guidebook that gives practical advice about getting hired in the media industries, particularly film, magazines, and book publishing. There is also a section that describes in detail what industry people do in their day-to-day jobs, whether it be on the business or creative side of the industries.

Drapes, M. R., & Lichtenberg, N. R. (2008). Vault guide to the top media & entertainment employers. New York: Vault Inc. (326 pages total)

This book provides profiles of 41 large companies, covering all facets of the mass media. While there is practical information about how to go about getting a job in these companies, the profiles provide much more detail about the companies themselves—how they are organized and how they developed over time.

Fellow, A. R. (2012). American media history (3rd ed.). Boston: Wadsworth/Cengage. (438 pages, including endnotes and index)

If you are interested in learning more about how the mass media developed in America, this book is a good source. Each of its 14 chapters focuses on the development of the various media from the colonial years to the present. It presents brief biographies of important media figures as it tells the story of the men and women whose inventions, ideas, and struggles helped shape the nation and its media system.

Neuman, W. R. (Ed.). (2010). Media, technology, and society: Theories of media evolution. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. (231 pages, including index)

This edited volume consists of 10 chapters written by various scholars. Seven chapters trace the development of a different mass medium—newspaper, telephone, film, radio, television, cable, and the internet. The remaining three chapters focus on theories of media evolution; privacy and security policies and the future of ownership.

Seguin, J., & Culver, S. H. (2012). Media career guide: Preparing for jobs in the 21st century (6th ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s. (122 pages, including index)

This is a practical guide to help college students prepare for a career in any facet of the mass media industries. Its seven chapters offer a lot of practical advice about how to develop a job search strategy; how to get an internship and maximize that experience; and how to write cover letters, resumes, and thank you notes.

Keeping Up to Date

· U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (https://www.bls.gov/ooh/management/advertising-promotions-and-marketing-managers.htm)

This is a website run by an agency of the federal government that reports information on all kinds of occupations in the United States, including salaries, duties, and required educational training. The above URL is for the Occupational Outlook Handbook page for advertising, promotions, and marketing managers.

· Statistical Abstract of the United States (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/icts.html)

The Department of Commerce releases a new statistical abstract every year. For updates on the material in this chapter, go to the section on information and communication.

· Vault.com (http://www.vault.com/wps/portal/usa)

This website provides useful information about various industries; particularly relevant to media literacy are the industries of publishing, newspapers, internet and new media, music, broadcast and cable, advertising, and public relations.

· Zap 2 It (http://www.zap2it.com/)

This website provides ratings of television shows and figures about the popularity of various Hollywood movies.

EXERCISE 5.1

SPECULATE ABOUT THE FUTURE OF THE COMPUTER/INTERNET INDUSTRY

This exercise gives you a chance to use what you have learned so far about how the media industries develop over time and what the current state is now.

FIVE-YEAR VISION

Try to imagine the mass media five years from now. What vision do you have of the media environment? Think about the following questions as you clarify your vision of the future.

1. What will be the dominant mass medium?

2. How will the existing media change to adapt to the rise of the digital media?

1. How will they redefine themselves?

2. Will they be able to identify new needs in the population that they can satisfy and thus allow them to survive?

3. Will any of the existing mass media disappear in five years?

1. If so, why will they have disappeared?

TWENTY-YEAR VISION

Try to imagine the mass media two decades from now. What vision do you have of the media environment? Think about the following questions as you clarify your vision of the future.

1. What will be the dominant mass medium?

1. Will it be a medium that exists now or will there be a new medium?

2. Which of the existing media will still be around?

1. What did these media do to survive?

3. Which of the existing media will have disappeared?

1. Why will they have disappeared?

EXERCISE 5.2

EXAMINING INDIVIDUAL MEDIA BUSINESSES FOR WORKFORCE PATTERNS

SELECT A MEDIA COMPANY TO ANALYZE

If you are thinking about pursuing a career in the media, select a company that you might like to work for and go to that company’s website. Search the website to find answers to the following questions.

1. How many people work at this company?

2. How are the employees organized?

1. By different levels (management, mid-level employees, low-level clerks)

2. By departments (for different functions: production, sales, etc.)

3. How many of the employees are women and how many are men?

4. Are there gender differences across levels or departments?

5. Can you find any recruiting information (profiles of the kinds of employees who work there, listings for actual jobs for which they are soliciting applications)?

SELECT A SECOND MEDIA COMPANY TO ANALYZE

Find a second company in the same industry and the same location, if possible. If you selected a radio station in the above part, then try to find a second radio station in the same market to analyze in this part. Answer the same five questions as above.

SELECT A THIRD MEDIA COMPANY TO ANALYZE

Find a third company in a different industry. If you selected radio stations in the above parts, then try to find a television station, newspaper, magazine, recording studio, or computer/internet company to analyze in this part. Answer the same five questions as above.

LOOK FOR PATTERNS

1. Compare and contrast the first two companies you analyzed.

1. How were the two companies the same as far as workforce patterns?

2. How were the two companies different as far as workforce patterns?

3. Did the patterns you found match the general patterns presented in the text?

4. Based on your analysis, which company would you prefer to work for and why?

2. Compare and contrast the companies across the two industries you analyzed.

1. How were the two industries the same as far as workforce patterns?

2. How were the two industries different as far as workforce patterns?

3. Did the patterns you found match the general patterns presented in the text?

4. Based on your analysis, which industry would you prefer to work for and why?

A company’s website might not present all the information you need to answer the complete set of questions in this exercise. Be creative in looking for other sources of information. Do a search of business periodicals (such as Wall Street Journal, Money Magazine, Fortune, etc.). Look for blogs. Search for books; most large media companies have at least one book written about them.

Descriptions of Images and Figures

Back to Figure

This graph plots the years on the x axis and the kinds of mass media on the y axis. These are: books, newspapers, magazines, film, recordings, radio, broadcast TV, cable TV, and digital.

Each of the horizontal stacked bar seen for each kind of the above forms of media is divided into the following stages through the years on the x axis from 1400 to 2020:

Innovation

Penetration

Peak

Decline

Adaptation

For books, these are the approximate years for each of the stages listed above:

Innovation: 1450 – 1800

Penetration: 1800 – 1950

Adaptation: 1950 – 2020

For newspapers, these are the approximate years for each of the stages listed above:

Innovation: 1598 – 1860

Penetration: 1860 – 1911

Peak: 1911 – 1930

Decline: 1930 – 1950

Adaptation: 1950 – 2020

For magazines, these are the approximate years for each of the stages listed above:

Innovation: 1720 – 1870

Penetration: 1870 – 1931

Decline: 1931 – 1950

Adaptation: 1950 – 2020

For film, these are the approximate years for each of the stages listed above:

Innovation: 1890 – 1901

Penetration: 1901 – 1921

Peak: 1921 – 1942

Decline: 1942 – 1975

Adaptation: 1975 – 2020

For recordings, these are the approximate years for each of the stages listed above:

Innovation: 1889 – 1921

Penetration: 1921 – 1970

Adaptation: 1970 – 2020

For radio, these are the approximate years for each of the stages listed above:

Innovation: 1909 – 1922

Penetration: 1922 – 1940

Peak: 1940 – 1954

Decline: 1954 – 1971

Adaptation: 1971 – 2020

For broadcast TV, these are the approximate years for each of the stages listed above:

Innovation: 1930 – 1941

Penetration: 1941 – 1950

Peak: 1950 – 1980

Decline: 1980 – 2000

Adaptation: 2000 – 2020

For cable TV, these are the approximate years for each of the stages listed above:

Innovation: 1940 – 1960

Penetration: 1960 – 1990

Decline: 1990 – 2000

Peak: 2000 – 2020

For digital, these are the approximate years for each of the stages listed above:

Innovation: 1980 – 2000

Penetration: 2000 - 2018

Peak: 2018 – 2020