12

The United States, the leading coffee-drinking nation of the world, conform[s] in general to the coffee-pattern—non-conservative, self-assertive, dynamic. . . . Coffee has . . . expand[ed] humanity’s working-day from twelve to a potential twenty-four hours. The tempo, the complexity, the tension of modern life, call for something that can perform the miracle of stimulating brain activity, without evil, habit-forming after-effects.

—Margaret Meagher, To Think of Coffee (1942)

On September 1, 1939, Hitler’s blitzkrieg stormed across the Polish border. Europe was at war, and a market for some 10 million bags of coffee—a little less than half the world’s consumption at the time—snapped shut. As in the previous world war, Scandinavian countries initially bought heavily for resale to warring nations, but Germany’s quick march through Europe early in 1940 soon closed off those ports. Besides, German U-boats made crossing the Atlantic—or even steaming from Santos to New York—extremely hazardous.

Suddenly the old Brazilian idea of a coffee agreement didn’t seem so repugnant to other Latin American producers or to the United States government—at least not its foreign policy wing. Colombia, threatened by Brazil’s open-the-floodgates policy and the wartime closing of the European markets, asked the U.S. State Department to help implement an accord. Meanwhile, green coffee prices plummeted.

Goose-stepping in Guatemala

With startling German military successes early in the war, the prospect of nazified neighbors to the south seemed all too real. Many of the 5,000 Germans in Guatemala were open Nazi sympathizers. In the northern province of Cobán, Germans owned 80 percent of all arable land. In addition, Germans controlled the prominent banking-export house of Nottebohm Brothers and many of the country’s coffee export firms.

Still, there were a number of German Guatemalans who had no use for Hitler. Walter Hannstein, for instance, born in Guatemala in 1902, had grown coffee all of his adult life. He cared only for his family plantation, not fascist megalomaniacs halfway around the globe.73 Similarly, Erwin Paul Dieseldorff and his son, Willi, who inherited the huge Guatemalan coffee holdings in 1937, were opposed to the Nazi government.

Local Gestapo members brought increasing pressure to bear on non-Nazi Guatemalan Germans, sometimes threatening them with violence. The Nazis compiled a secret list of forty “unpatriotic” Germans who were to be executed once Germany won the war and took over Guatemala.

Gerhard Hentschke, the commercial attaché to the German embassy in Guatemala City, deluged Guatemalans with Nazi propaganda (in Spanish) through newspapers, radio, and libraries. Distributors of German goods enclosed Nazi literature in cases of merchandise. Otto Reinebeck, the Nazi minister for all Central America, was headquartered in Guatemala. Reinebeck invited groups of German coffee growers to parties, and soon the German Club flew the swastika alongside the flag of the old monarchy. Nazi sympathizers marked the underside of strategic bridges with swastikas to let invading German forces know that these bridges were to be blown up.

Hammering Out a Coffee Agreement

Given this context, it is easy to understand the alacrity with which the U.S. State Department hastened to assure coffee growers that they would support an agreement that would save the coffee industries and economies of Latin America. The United States was now the only market for their coffee. If the United States took advantage of the situation to extort ever-lower prices, it would virtually throw an embittered, impoverished Latin America to the Nazis or Communists.

On June 10, 1940, five days after Hitler invaded France, the Third Pan American Coffee Conference convened in New York City, with delegates from fourteen producing countries. The conference assigned the task of quota divisions to a three-man subcommittee, which thrashed out a compromise. The Inter-American Coffee Agreement, which was to be renegotiated on October 1, 1943, allowed for 15.9 million bags to enter the United States—nearly a million over the estimated actual U.S. consumption at the time, which would ensure U.S. citizens of enough coffee while at least providing a quota ceiling so that prices would not decline to absurd levels. Brazil would get the lion’s share of the quota—not quite 60 percent—with Colombia snaring just over 20 percent. The rest was divided between other Latin American producers, with a token 353,000 bags left for “other countries” that included Asian and African producers.

Although the conference closed on July 6, 1940, it took nearly five months to achieve an agreement that all of the participants would sign. Mexico and Guatemala were major holdouts, demanding a larger share of the pie. On July 9, Guatemalan dictator Jorge Ubico told John Cabot, the American chargé, that his country’s proposed 500,000-bag quota was completely unacceptable. “The mere publication of the plan locally,” the pro-German Ubico informed Cabot, “would result in driving this country commercially into the hands of Germany as soon as commercial relations with Germany can be resumed.”

As the pending quota agreement appeared in jeopardy, coffee prices continued their free fall, eventually reaching 5.75 cents a pound in September 1940, the lowest price in history.74 Eurico Penteado of Brazil and Sumner Welles of the United States, working through the already-established Inter-American Financial and Economic Committee, agreed to tweak the quotas in a compromise that finally brought all of the signatories to the table.

Welles met on November 20, 1940, with representatives of fourteen Latin American coffee-producing countries to sign the agreement in English, Spanish, Portuguese, and French. The New York Times reported that it was “an unprecedented agreement” that would erect “economic bulwarks against totalitarian trade penetration.”

1941: Surviving the First Quota Year

The first year of the agreement, which ran retrospectively from October 1, 1940 (when the new Brazilian harvest began to arrive in the United States), through September 30, 1941, was marked by controversy and uneasy compromise. In the first few months of 1941, coffee prices rose swiftly in response to the newly signed agreement. At first American coffee companies weren’t alarmed. W. F. Williamson, secretary of the National Coffee Association, put it succinctly: “The American consumer does not require, and will not insist on having coffee at prices which mean bankruptcy to Latin American producing countries.” Business Week noted that higher coffee prices would “cushion the impact of the war on the economy of Latin American countries,” while allowing them to purchase more goods from U.S. manufacturers.

By June prices had nearly doubled from their lows of the previous year. At the Coffee Board meetings of the Inter-American Coffee Agreement, the producing countries resisted the suggestion put forward by American representative Paul Daniels to increase the quotas. Both Brazil and Colombia flouted Daniels’s request by increasing the official minimum price at which they would sell their coffees.

Leon Henderson, head of the newly created U.S. Office of Price Administration (OPA), took notice. The New Deal advocate had never approved of the coffee quota agreement. In July, when Brazil announced another minimum-price increase, Henderson blew up. “The unmistakable attitude of the producing countries to date,” Henderson wrote, was: “‘Here is a chance to make a killing.’” He threatened to suspend the quota agreement. Daniels subsequently invoked the right of the United States under the coffee agreement unilaterally to increase the various quotas without the consent of the producers. On August 11 quotas were officially increased by 20 percent. The ploy worked, as prices began to subside.

In spite of numerous problems, the coffee agreement saved the Latin American coffee industry, and relations between the United States and Latin America seldom had been more amicable. During 1941, per-capita coffee consumption in the United States had risen to sixteen and a half pounds—a new record.

In December six Latin American “coffee queens,” funded by their governments, arrived in New York for a triumphant U.S. tour. Eleanor Roosevelt hosted them on her show, Over Our Coffee Cups, which stressed the theme, “Get More Out of Life With Coffee.” The coffee queens were scheduled to appear at the Waldorf Astoria a week later for a grand Coffee Ball—but the Japanese upstaged them.

Coffee Goes to War—Again

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. OPA czar Leon Henderson froze coffee prices at their December 8 levels, explaining that the U.S. war entry “created a situation in which the inflationary tendencies in the price of coffee might again be intensified.”

The army requisitioned 140,000 bags a month, ten times as many beans as they had the previous year, to supply what would become a 32.5 pound annual per-capita military addiction. One governmental dispatch listed coffee as an essential raw material, “highly important to help maintain morale, both in the army and at home.”

Although there were plenty of Latin American beans, shipping space was limited, with every available bottom devoted to the war effort. Now that the United States had entered the war, German submarines posed more of a threat. On April 27, 1942, the War Production Board limited roasters to only 75 percent of the previous year’s deliveries. The War Shipping Board took over the entire U.S. Merchant Marine fleet, and in June the Brazilians turned over their boats to the war effort as well, in return for promises that the U.S. Commodity Credit Corporation would buy all of the Brazilian coffee quota, even without available shipping. The War Production Board then took control of all coffee entering the United States, effectively ending a free market.

By September 1942 the supply situation had reached crisis proportions, with the coffee quota to roasters cut to 65 percent. On October 26 Leon Henderson announced that coffee rationing for civilians would begin in a month, allotting one pound every five weeks to anyone over the age of fifteen.

Henderson asserted that his coffee allowance meant 10.4 pounds for each adult—not much less than the per-capita consumption during the Depression. Coffee men pointed out, however, that the official per-capita figures included children. Adjusted for adult consumption only, the figures revealed that rationing cut coffee allotments by half.

Rationing threatened to undo all of the brewing directives the roasters had been trying to teach American consumers. Articles instructing housewives in the fine art of diluting good coffee appeared. Jewel advertised that consumers could “get up to 60 fragrant cups per pound.” President Franklin Roosevelt (who apparently didn’t listen to his wife’s radio program) suggested that coffee grounds be used twice. “The newspapers are full of what to use instead of coffee,” complained a Chicago coffee broker, “so we are getting malt, chick peas, barley, a concoction with molasses and cooked to a brown paste—anything to have a colored liquor.” Postum experienced a renaissance. High-quality blends such as Hills Brothers and Martinson’s also thrived. While Brazilian beans needed long transport, Colombian and Central American coffee had less distance to travel on ships and could also arrive by train across the Mexican border.

On February 2, 1943, the Germans lost at Stalingrad. From that point on, the war clearly turned in favor of the Allies. German submarines no longer posed much of a threat to Atlantic freighters, and coffee flowed more freely from Brazil. On July 28 President Roosevelt announced the end of coffee rationing. While the period of enforced coffee curtailment helped inure Americans to a weak brew, it also reinforced the national craving. During the rationing period, poet Phyllis McGinley penned an eloquent lament in which she spoke of the “riches my life used to boast”:

Two cups of coffee to drink with my toast,

The dear morning coffee,

The soul-stirring coffee,

The plenteous coffee

I took with my toast.

Coffee at the Front

The military supplied defense workers and troops with as much coffee as they could drink. Production went up when factory workers were allowed time off for a cup of coffee. The Quartermaster Corps, the military provision arm, roasted, ground, and vacuum packed coffee at four facilities and subcontracted to nineteen commercial roasters.

After D-Day the military shipped green beans overseas. Army coffee men jury-rigged roasters from gasoline drums when they couldn’t get industrial machines, roasting 12,000 pounds of coffee a day in an old Marseilles factory. Over fifty Mobile Units provided coffee and baked goods. In the Pacific theater of operations, staff sergeant Douglas Nelson, a former Maxwell House employee, erected a plant in Noumea, the capital of New Caledonia, where he roasted locally grown coffee. In Europe three hundred Red Cross “clubmobiles” dispensed coffee and doughnuts to troops along with books, magazines, cigarettes, and phonograph records.

As shown in this 1921 ad, coffee has always provided the pick-me-up that helps workers get through their day—providing a drug instead of rest, according to some critics.

G. Washington, the first major instant coffee, was so popular during World War I that doughboys asked for “a cup of George.”

Motorized vehicles revolutionized coffee delivery in the early twentieth century.

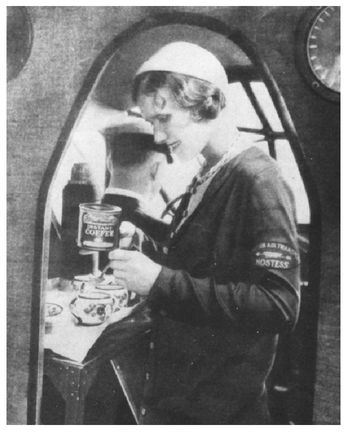

By the 1930s, coffee was taking to the air.

Alice Foote MacDougall clawed her way to success in the man’s coffee world, creating a chain of New York coffeehouses in the 1920s. “Fight, fight, fight until you win,” she wrote. “It is this kind of determination that man has acquired through long generations, and the woman who is to conquer in the business world must acquire it too if she is to succeed.” Still, she thought women should not be allowed to vote.

In the 1920s, Alice Foote MacDougall was inspired by a trip to Italy and replicated Italian decor in her elaborate New York coffeehouses.

In this 1934 cartoon ad (only one panel shown here), Chase & Sanborn provides alarming evidence that wife-battering was apparently acceptable, understandable behavior during the Depression—especially if the husband didn’t like the coffee. The company hoped that terrified wives would purchase Chase & Sanborn in hopes of avoiding such confrontations.

In Depression-era cartoons, “Mr. Coffee Nerves” created havoc, only to be “foiled again” by Postum.

This racist ad helped sell Maxwell House Coffee, just as the characters on the popular radio show did. The sound effects and acting were so convincing that many listeners waited hopefully on wharves for the mythical Show Boat.

Coming out of the Depression, Chase & Sanborn identified itself with the new jitterbug craze at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

In 1937, Mae West appeared on the “Chase & Sanborn Hour,” lewdly calling dummy Charlie McCarthy “all wood and a yard long.” But it was her Adam and Eve skit, in which she praised the serpent as a “palpitatin’ python,” that nearly got the show thrown off the air.

Coffee rediscovered its homeland in Africa during the 1930s, though in Kenya most of the coffee growers were white. Hence this racist ad from 1937.

In 1941, first lady Eleanor Roosevelt reached millions of listeners with her radio show, “Over the Coffee Cups,” sponsored by the Pan American Coffee Bureau.

For exhausted GIs fresh from the front lines of World War II, coffee was essential. It is little wonder that U.S. per capita consumption peaked just after the war.

U.S. soldiers would do almost anything for hot coffee during World War II, including wasting all their matches in the attempt.

During the 1950s, instant coffee provided middle-class Americans a quick, convenient, cheap pick-me-up—without concern for quality.

The “coffee break”—as a phrase and concept—was invented in 1952 by the Pan American Coffee Bureau. It quickly became a part of the language, as evidenced by this cartoon book.

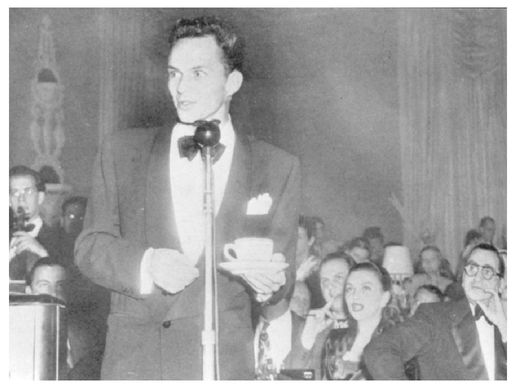

In his early teen heartthrob days, Frank Sinatra sang “The Coffee Song,” which immortalized “an awful lot of coffee in Brazil.”

Chock full o’ Nuts became a best-selling coffee in New York through such ads, once more playing the sexist theme.

During the fifties, coffee became an accepted part of American life, sanctioned by the police as an aid to safety.

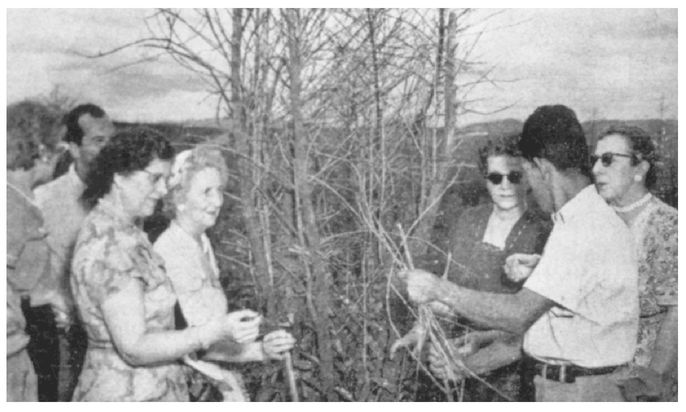

In 1954, when outraged Americans blamed Brazil for artificially boosting coffee prices, the Brazilian government flew U.S. housewives down to Paraná to see the frost damage for themselves.

In a desperate attempt to compete with the bigger corporations, family-owned Hills Brothers stooped to ads in the 1960s claiming that its coffee could be reheated without damage.

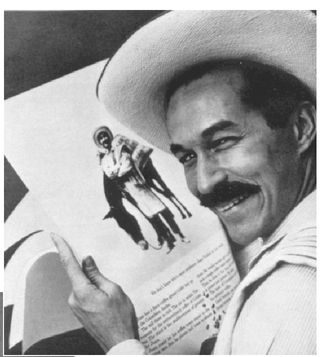

Beginning in 1960, the mythical Juan Valdez sold Colombian coffee in the United States. Today, the actor who plays him owns a silk-screen T-shirt factory along with a coffee farm, where he pays others to grow his crop.

Muppeteer Jim Henson launched his career in 1957 with coffee ads for Wilkins Coffee in which puppet Wontkins, who refused to drink the right coffee, was shot, branded, drowned, clubbed, slashed, frozen, and blown up.

Far from the comforts of home, the GI would do just about anything for a hot cup of coffee in a frigid foxhole, even if it was made from instant powder. The army provided lightweight aluminum foil packets of soluble coffee in K rations. By 1944, in addition to Nescafé and G. Washington, ten other companies, including Maxwell House, were making instant coffee, all of it requisitioned by the military. “Soldiers report that the capsules are easy to handle and the coffee simple to prepare,” wrote Scientific American in 1943. “Where a fire is not available, the powder may be mixed with cold water.” But to the exhausted grunt at the front, warmth meant everything. Bill Mauldin, a war cartoonist and chronicler, described an infantry platoon stuck in the mud, rain, and snow of the northern Italian mountains. “During that entire period the dogfaces didn’t have a hot meal. Sometimes they had little gasoline stoves and were able to heat packets of ‘predigested’ coffee, but most often they did it with matches—hundreds of matches which barely took the chill off the brew.” The American soldier became so closely identified with his coffee that G.I. Joe gave his name to the brew, a “cuppa Joe.”75 The military men also had quite a few other nicknames for coffee—depending on its strength or viscosity—including java, silt, bilge, sludge, mud, or shot-in-the-arm.

The American soldier may have had to settle for cold, instant coffee, but at least he had real coffee. By the summer of 1943, genuine coffee in Nazi-occupied Netherlands cost $31 a pound, when it was available at all. Even had they been able to get coffee beans, many European roasters couldn’t have done much with them. In Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Italy, bombs had reduced roasting plants to rubble.

To add insult to injury, the British sent Royal Air Force squadrons that in mock bombardments dumped small bags of coffee beans over Nazi-occupied territory. The idea, a contemporary journalist wrote, was that “wherever the coffee beans fell, dissatisfaction would blossom.” The coffee bombs failed to end the war.

Denazifying Latin America

Under U.S. coercion, German, Italian, and Japanese settlers in Latin America—many of whom were coffee growers—were increasingly subjected to official blacklists. Their farms and businesses were confiscated, and in many cases they were actually deported and incarcerated in U.S. internment camps.

In Brazil, where there were sizable populations of all three nationalities, dictator Getúlio Vargas had been slow to side with the Americans. As German victories piled atop one another in the early part of the war, Vargas gave a protofascist speech in which he praised “nations imposing themselves by organization which is based on a sentiment of the Fatherland, and sustained by the conviction of their own superiority.” Pearl Harbor, however, swung Vargas decisively toward the U.S. side, and as German submarines sank Brazilian ships, public outrage burst forth. In March 1942 Vargas ordered the confiscation of 30 percent of the funds of all 80,000 Axis subjects in Brazil, though only 1,700 or so were Nazi party members. In August Brazil officially declared war against the Axis powers.

In Guatemala, dictator Jorge Ubico abandoned his German coffee friends in the wake of Pearl Harbor. With Ubico suddenly assuming a strong pro-American posture, a blacklist of German coffee concerns—prepared months before under pressure from the U.S. State Department—went into effect on December 12, 1941. “Interventors” took over farms owned by most native Germans and even some Guatemalan-born Germans. The government ran the German-owned export firms. Many Germans, even very old men, were arrested and shipped off to Texas internment camps beginning in January 1942. Germans were grabbed from all over Central America. Many were traded back to Germany (where they may never have lived) in return for American civilians interned behind enemy lines.

A total of 4,058 Latin American Germans were kidnapped, shipped to the United States, and interned largely to “hold them in escrow for bargaining purposes,” as an internal U.S. State Department memo put it.76 Another motivation may have been to eliminate business competition. Nelson Rockefeller, who headed the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs and supervised counterintelligence efforts, emphasized the necessity of preventing German expansion in “America’s backyard.” Berent Friele, the coffee czar, left A & P to become Rockefeller’s Brazilian agent, helping him survey the Amazon for future development.

In an extraordinary twist of logic, the Latin American Germans were dragged into the United States, then imprisoned for illegal entry into the country.77 Walter Hannstein nearly lost La Paz, his coffee finca in western Guatemala, even though he had been born in Guatemala, was married to a U.S. citizen, and had pronounced anti-Nazi views. Hannstein’s farm and freedom were saved when he produced the list of forty Guatemalan Germans earmarked for elimination by the Nazis. Hannstein’s was the thirty-sixth name on the list.

The U.S. Industry Survives the War

The U.S. coffee industry adjusted to war conditions. With most of its male employees at the front, Jewel turned to female wagon route drivers for the first time, discovering that they could sell just as well as men. Women also proved their worth in coffee factories, not only in routine, menial jobs but as roastmasters and supervisors.

In 1942 Maurice Karker joined the War Department (though remaining chairman of the board), leaving the Jewel presidency to Franklin Lunding. Due to Karker’s influence and Jewel’s contract to make 10-in-1 ration packs, with food and coffee for ten people for one day, the company received priority on restricted machinery parts and labor to keep their delivery trucks running. By the war period, 65 percent of Jewel’s sales volume came from its retail stores, but over 60 percent of its profits still derived from the lucrative wagon routes.

Maxwell House made patriotic appeals for its coffee. “Coffee’s in the fight too! With the paratroopers . . . in the bombers . . . on board our Navy ships . . . the crews turn to a steaming cup of hot coffee for a welcome lift.” General Foods urged housewives to put up fruits and vegetables in empty Maxwell House jars, doing “your bit for Uncle Sam.”

The third-generation Folgers both went to war in their own ways. James Folger III was appointed to the War Production Board, while his brother, Peter, joined the marines. The war swelled California’s coffee-drinking population, as many who had migrated to work in the war plants stayed. Veterans who had embarked from San Francisco for the Pacific theater of war returned to settle down. The state’s population nearly doubled in a decade.

In 1940 Hills Brothers had opened an eight-roaster factory in Edgewater, New Jersey, from which it planned to supply the Midwest and, it hoped, eventually the entire East, though the war interrupted its expansion plans. Owing to a shortage of manpower, Hills Brothers let Elizabeth Zullo and Lois Woodward into the cupping room, formerly a sacred male inner sanctum.

Chase & Sanborn had been struggling to maintain profits even before the war. Its parent company, Standard Brands, had traditionally been able to rely on Fleischmann’s Yeast as its core moneymaker. But the American housewife had stopped baking bread, the repeal of Prohibition ended the yeast market among illicit home brewers, and the patent medicine claims for yeast cures fizzled. The coffee market didn’t offer the same profit margins. As a result, Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy were cut to a half-hour, while Dorothy Lamour vanished from the show. The Chase & Sanborn freshness claim, formerly based on twice-weekly deliveries along with yeast, were rendered moot by other brands’ vacuum packs.

With profit margins dropping below 10 percent, and Chase & Sanborn’s market share falling several percentage points behind that of Maxwell House, the company finally opted for vacuum cans in November 1941. The next month the company brought in James S. Adams from Colgate-Palmolive-Peet as president, just in time for Pearl Harbor. Adams completely reorganized the company, replacing key executives and suspending dividends. He tried to increase coffee sales by adopting a glass jar vacuum pack, but the war environment did not favor shifts in brand preference.

The war essentially put the U.S. coffee industry on hold, with roasters simply maintaining their positions. The major roasters such as Maxwell House dominated an industry that had seen considerable consolidation. In 1915 over 3,500 roasters provided coffee to the U.S. consumer. By 1945 there were only 1,500 roasters. Of those, only 57—less than 4 percent of the total—roasted more than 50,000 bags a year.

Good Neighbors No Longer

As the war neared its end, the price ceiling on coffee entering the United States—held at 13.38 cents a pound since 1941—became increasingly onerous for the producing countries. Although the Office of Price Administration (OPA) had allowed increases for consumer items grown domestically, it stubbornly refused to raise coffee prices. By fall 1944 the situation in Latin America had become critical. In the New York Journal of Commerce, El Salvador’s Roberto Aguilar pleaded for a price rise for destitute growers. “They’re making no profit today; they’re not even holding their own.” Because they couldn’t pay better wages, the growers were losing workers to more remunerative industrial jobs.

On November 20, 1944, Brazil’s Eurico Penteado wrote an open letter to George Thierbach, the president of the National Coffee Association, which the Pan American Coffee Bureau ran as a paid advertisement in over eight hundred U.S. newspapers. Penteado explained that the ceiling price was still 5 percent below the average price of the previous thirty years. “This state of affairs is already resulting in the abandonment of millions and millions of coffee trees throughout Latin America,” he pointed out, the majority of which were Brazilian. São Paulo coffee production had declined to a third of its 1925 level. So had prices. Yet production costs had doubled. The Brazilian coffee-burning program, in which 78 million bags had gone up in smoke since 1931, finally had ended, and there was little surplus left.

The Central American growers were equally hard-pressed. “Workers now pay $14 for shoes that formerly sold for $4.50,” complained an El Salvador coffee grower. “Wages, already twice what they used to be, will have to go higher.” Yet these realities did not appear to concern the American consumer. “The U.S. does nothing but talk about 5-cent-a-cup coffee as being something unalterable.” The mild coffee-growing countries could not afford to ship their best coffee at OPA prices, so they began to send lower grades that had not been properly processed or sorted. Many growers withheld their crops entirely, waiting for better prices.

OPA turned a deaf ear to these anguished arguments—which is surprising, since Chester Bowles now headed the agency. Though he had made his fortune advertising Maxwell House, Bowles was now just another bureaucrat who apparently had lost his ability to write clear copy. “It is the view of this Government,” he intoned, “that its decision not to increase the maximum prices of green coffee is essential to the maintenance of price controls that are adequate to withstand the inflationary pressures with which this country is now faced.”

Bowles’s heartless words reflected in part an overall shift in the government’s attitude. Sumner Welles, the chief architect and promoter of the Good Neighbor Policy, had been forced from the State Department in 1943, and sympathetic Paul Daniels left the Coffee Board of the Inter-American Agreement shortly thereafter, replaced by Edward G. Cale, a functionary who worked against the coffee-growing countries even while serving on their board. As a former State Department man later recalled, “After the fall of France and during the dark days following Pearl Harbor, the United States had ardently courted Latin America.” Now, however, “we had next to no time for [its] problems.”

Even when the war ended in 1945, the price ceilings remained in place. With the Brazilian economy in crisis, longtime dictator Getúlio Vargas was forced to resign by a dissatisfied military on October 29, 1945.78 Though coffee prices were not directly responsible for the dictator’s ouster, they added to the public’s general discontent. During this crisis period, Brazil abolished its National Coffee Department and reduced its commitment to coffee advertising. Other members of the Pan American Coffee Bureau followed suit.

On October 17, 1946, OPA finally released its stranglehold and eliminated the price ceiling. “Liberated,” the single-word headline in the Tea & Coffee Trade Journal announced. The first free contract for Santos sold at 25 cents a pound. In following years the price would rise steadily along with inflation.

The Legacy of World War II

More than $4 billion in coffee beans were imported into the United States during World War II, accounting for nearly 10 percent of all imports. In 1946 U.S. annual per-capita consumption climbed to an astonishing 19.8 pounds, twice the figure in 1900. “Way down among Brazilians, coffee beans grow by the billions,” crooned Frank Sinatra, the new teen idol, “so they’ve got to find those extra cups to fill. They’ve got an awful lot of coffee in Brazil.” Moreover, according to the lyrics, in Brazil you couldn’t find “cherry soda” because “they’ve got to fill their quota” of coffee.

During the war the U.S. civilian population had limited access to soft drinks because sugar rationing curtailed the major ingredient in Coke and Pepsi. But the ever-resourceful carbonated giants still found ways to promote their drinks. Pepsi opened Servicemen’s Centers where soldiers could find free Pepsi, nickel hamburgers, and a shave, shower, and free pants pressing. But it was the Coca-Cola Company, through lobbying and insider contacts, that pulled off the major wartime coup: getting its drink recognized as an essential morale-booster for the troops. As such, Coke for military consumption was exempted from sugar rationing. Not only that, some Coca-Cola men were designated “technical observers” (T.O.s), outfitted in army uniforms, and sent overseas at government expense to set up bottling plants behind the lines. When a soldier got a bottled Coca-Cola in the trenches, it provided a compelling reminder of home, even more than a generic cup of coffee. “They clutch their Coke to their chest, run to their tent, and just look at it,” one soldier wrote from Italy. “No one has drunk theirs yet, for after you drink it, it’s gone.”

“The existing carbonated beverage industry is counting on an immediate 20 percent increase in volume just as soon as the war is over,” said coffee man Jacob Rosenthal in 1944, observing that teenagers overwhelmingly preferred Coke to coffee. “Today to some 30 million school age youngsters a drink means milk, cocoa, soda or coke. We suffer from . . . anti-coffee propaganda with the youngster market despite the fact that cola drinks, cocoa and chocolate have about as much caffeine as coffee when served with cream and sugar.” He urged coffee men to mount a campaign to match the soft drink appeal. “The fact is that as a group these adolescents like to think and act grown-up—and coffee is what the grown-ups drink.” So why not capitalize on that yearning for adult status?

Few coffee men were listening, and the baby boom generation, just then being born, would be devoted to Coke and Pepsi, while coffee itself would become increasingly poor in quality as companies used cheaper beans. A sad chapter in the coffee saga was about to begin.