CHAPTER SIX

WHEN WE VISIT a ruined castle, its former beauty is often difficult to picture. To see the whitewashed walls gleaming and the flags fluttering in the breeze, we have to screw up our eyes and work our imaginations hard. However noble and refined the interior may once have been, chances are it now seems crude and Spartan. We constantly have to remind ourselves that, despite the dripping rainwater, grassy floors and mossy walls, castles were once sophisticated, sumptuous buildings, full of light, warmth and good cheer.

Raglan Castle, however, is an exception. Hidden in the hills of south Wales, this magnificent building is one of the grandest ruins in Britain, where every inch of stonework speaks of past splendour. Heraldic devices and coats of arms still adorn the walls; gargoyles grimace at us over the gate. The stained glass is gone from the windows, but the fine stone tracery remains intact. Everything seeks to persuade us that this was once the most splendid place imaginable.

With a great tower and a moat, two courtyards and gatehouses, and built on the site of an earlier motte and bailey, Raglan is almost overqualified as a castle. Yet for all its bona fide credentials, it feels more like an Oxford college or an Inn of Court, suddenly abandoned after some unforeseen tragedy. The evidence of past luxury only reminds us of its present absence, and suffuses the castle with a terrible sense of loss. How did it happen, the curious visitor will want to ask, that this wonderful place, where the walls still whisper of former glories, became so desperately sad?

Travel back, for a moment, to the year 1640, and meet Raglan’s owner: Henry Somerset, Marquis of Worcester. At sixty-four years old, he is a man in the autumn of his life, and as such he has seen a lot of water flow under the bridge. Looking back to his boyhood, he can still remember the dark days when the Spanish Armada threatened England with invasion. He can also recollect happier times; his teenage years at Oxford, and his early twenties reading law at the Middle Temple. Most of all, he is able to reflect with some satisfaction on a long and successful career as a loyal servant of the Crown. Henry has been a courtier to no less than three successive monarchs: Elizabeth I, James I and Charles I.

Now, however, he has more or less withdrawn from public life, to spend more time with his family. His long marriage to Countess Anne, celebrated forty summers ago, came to an end with her death the previous year. All that remains to him now is the prospect of playing out his final years at Raglan, surrounded by his many children and grandchildren, safe in the knowledge that, in the fullness of time, they will inherit his castle and fortune. To him, these seem modest hopes and ambitions. After all, his ancestors built the castle some two hundred years ago, and his family have enjoyed its custody ever since – he can see no reason why they should not go on enjoying it for another two hundred. England is the most peaceful place in Europe. No one alive can remember having to defend a castle in war.

The marquis does not know it, but war is just around the corner – the bloodiest war ever fought on British soil. Castles everywhere are about to dragged back into military service. From Corfe to Conway, from Pembroke to Pontefract, sieges are about to take place on a scale unseen for centuries. This time, however, castles will not be up against the trebuchets and crossbows of former times, but the latest and deadliest technologies of the age – the cannon and the mortar. And these killing machines will eventually come in record numbers to Raglan, to take part in one of the biggest, longest and hardest-fought sieges of the entire conflict.1

This conflict was the English Civil War, as it is still generally known, despite its Scottish and Irish dimensions and the fact that the fighting also extended into Wales. Raglan Castle owes its present appearance to its experiences during the war, and the decisions taken by Henry Somerset in the summer of 1646.

The castle has an importance independent of its role during the 1640s, for it was one of the last great castles to be built in England (or Wales). Its massive scale and strength reflects the wealth and ambitions of its builders, a father and son team who, in classic late-medieval style, found fame and fortune on the battlefields of France. William ap Thomas (Henry Somerset’s great-great-great-great-great grandfather) was a man very much in the mould of Sir Edward Dallingridge. Despite his fairly humble gentry background, he distinguished himself in the Hundred Years War (fighting alongside Henry V at Agincourt), prospered in the service of a great magnate (in this case, the Duke of York), and married a rich lady called Elizabeth. Because she was a widow, with sons by a previous marriage, William only acquired a life interest in her estate. In 1432, however, he purchased the manor of Raglan from his stepson for £666, and began to build the castle.

In 1445, William ap Thomas died, and his son, also William, picked up the building programme where his father had left off. Also a veteran of the French wars, William junior further increased his family’s fortunes by investing heavily in the wine trade and supporting the Duke of York in his bid for the English throne. In 1468, the duke, now king, rewarded William’s loyalty by making him Earl of Pembroke. The speed of the earl’s rise was outstripped only by the rapidity of his fall. Within a year both he and his career had been abruptly cut short – when the Yorkists lost the battle of Edgecote, he was beheaded.

By this stage, however, Raglan Castle was almost finished, and was more or less the same size and shape that it is today. Most of the castle is the work of the younger William, whose investment was longer and heavier than that of his father. The contribution of William senior, however, was by no means negligible. In particular, he was responsible for Raglan’s most prominent and distinctive feature – its huge, isolated great tower. Even today, though sadly much reduced, this part of the castle dwarfs the other buildings; when it was first built it stood five storeys and over a hundred feet high.

Between them, the two Williams had built a castle in the very latest French fashion. With its hexagonal towers, prominent machicolations (currently only visible over the gatehouse and the closet tower, but probably once crowning the top of the great tower, too) and ‘bascule’ drawbridges, Raglan has close affinities with contemporary castles in Brittany and along the River Loire. As with other late medieval castles, such flamboyant design features raise the question of style over substance. Evidently there was a desire on the part of the builders to create a castle that was pleasing to the eye; if you look carefully at the machicolations on the top of the gatehouse, you will see gargoyles grinning back down at you. Such decorative features are more common on churches and colleges than castles. In addition, some of the military hardware seems either spurious or, at best, ill conceived. For example, the gun-loops in the gatehouse, like those at Bodiam, have been judged ineffective by some modern commentators, since they do not offer a comprehensive field of fire.

But the defensibility of Raglan is not really in doubt. The drawbridges, now replaced by spans of stone, were once fully operational. The portcullises, now also vanished, patently worked. Although the castle is not concerned with protecting itself to the same degree as, say, Caernarfon, it nevertheless has a passive strength that puts it on a par with castles of an earlier age. The great tower, in particular, has walls that are ten feet thick.

The big question that hangs over Raglan Castle is not whether its defences ‘work’ (to the extent that it had them, they worked just fine), but why its owners bothered to build them in the first place. By the time of the younger William’s death in 1469, few people in England were building castles any more. The country had been mostly peaceful for well over a century, largely as a result of sending its warlike young men to fight in France. True, when the Hundred Years War finally clattered to a halt in 1453, there was trouble at home. For the next thirty years, England witnessed a series of domestic conflicts known as the Wars of the Roses. These, however, far from being the bloody nightmare depicted by Shakespeare, were intermittent, small-scale dynastic affairs. While they could have dire consequences for the individual aristocrats involved (William, Earl of Pembroke, was not the only man to lose his head), they had no effect whatsoever on architectural fashions. Nobody felt the need to invest in elaborate defences because of such minor civil disturbances. Equally, with the end of the war in France, no one was making a fortune from soldiery any more either. By the century’s end, the people who were really prospering were not soldiers but courtiers – men who worked in the service of the Crown. When they built new homes, they forsook all the cunning and elaborate forms of defence that their forebears had devised, and lavished their money on courtyard houses. A well-known example is Hampton Court, built in the early part of the sixteenth century by Henry VIII’s one-time first minister, Cardinal Wolsey.

While Henry VIII’s nobility set about building non-defensible residences like Hampton Court, the king himself constructed a chain of tiny coastal forts, stretching from Pendennis in Cornwall to Deal in Kent. Throughout the Middle Ages, the English Crown had been growing steadily stronger, increasingly able to raise large national taxes and fund a bureaucracy on an ever greater scale. By Henry’s day the Crown was also willing to take on the burden of defending its subjects from foreign attack. When they first appeared, Henry’s new defences were christened ‘castles’, and surviving examples (like Camber, Sandwich and Walmer) still go by the name of castle today. Without being too judgmental about what is and what is not a castle, however, I think they are rightly excluded from the castle club. Their function is purely military – they have no residential dimension at all.

By the start of the sixteenth century, therefore, castles (according to my definition, at any rate) were already a thing of the past. Everywhere you travelled, the great fortresses of earlier centuries stood empty, their owners having moved out into comfy courtyard houses. Very quickly, these abandoned buildings fell into disrepair. Castles might look tough, but at the end of the day they require a lot of care and affection. You have to clean out their drains and their gutters, and repair holes in the roofs. Surveys of royal castles, which survive from the middle of the thirteenth century, make it perfectly clear that the king and his custodians fought a constant battle against the elements just to keep them in working order. A few years of neglect or one big storm was enough to wreak considerable havoc with the fabric of a building. Travelling writers and official surveyors in the sixteenth century noted that most castles were in a very bad way.

Only a minority of aristocrats stuck it out in castles, either because abandoning the ancestral pile was unconscionable, or because the castle was sufficiently well-appointed to meet their more refined requirements. In the case of Raglan, it was probably a mixture of both reasons. The castle had been in the same family for generations, and as a fifteenth-century building it was also extremely well provided and handsomely fitted out. Nevertheless, the sixteenth-century owners of Raglan, like other die-hard castle owners with less up-to-date models, still felt compelled to upgrade the medieval buildings to bring them into line with the latest architectural fashions. It was essential to keep up with the owners of courtyard houses in terms of luxury and refinement. If you were a castle owner in the sixteenth century, you had to make home improvements.

The man who undertook these improvements at Raglan was the grandfather of the Marquis of Worcester, William Somerset (d. 1589). Most of his alterations were concentrated on the castle’s eastern courtyard, which he enlarged by destroying an earlier range of buildings and constructing a new office wing. He also substantially altered the castle’s hall, rebuilding its eastern wall (again, part of the eastern courtyard) and fitting a handsome new hammer-beam roof of Irish oak. At the same time, Somerset improved the hall’s service arrangements, in particular by extending the size of the buttery. The castle was brought up to speed to cater for the more demanding tastes and larger household of an Elizabethan courtier. The commodity that Somerset really craved in abundance, however, was light. Like other Tudor castle owners, he wanted to make his dingy medieval castle as bright and sunny as a courtyard house. This meant, of course, big new windows.

In the second half of the sixteenth century, the replacement window trade in England was booming, thanks to a minor revolution in the glazing industry. Glazed windows had been the norm for aristocratic dwellings since the thirteenth century, but glass could only be produced in small sheets, and was expensive to manufacture. Curiously, the sudden improvement in the later sixteenth century cannot be linked to any dramatic technological change (that came slightly later, in the early seventeenth century, when glaziers began to use coal-fire furnaces). The advances made in William Somerset’s day were due solely to the arrival of Continental artisans, equipped (it seems) with nothing more than greater savoir-faire than their English counterparts. Coming from Normandy and Lorraine, attracted no doubt by the prospect of untapped markets, these glaziers set up shop in Sussex and Staffordshire and promptly made a fortune. Windows were suddenly cheaper and bigger. For the less well off, this meant that they could enjoy the benefits of a product that had hitherto been restricted to only the very wealthy. For the very wealthy, it meant they could indulge themselves with fantastical amounts of glass. Elizabethan courtiers began to build great ‘prodigy’ houses, with hundreds of giant windows. At Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, such was the scale of the glazing job that locals coined the rhyme ‘more glass than wall at Hardwick Hall’. For castle owners, the new market in glass meant that the small narrow windows of yesteryear could be ripped out and replaced with grand new ones. At Kenilworth Castle, the twelfth-century keep had large windows inserted on the first floor. At Carew, a late thirteenth-century castle in Pembrokeshire, enormous ranges of glass were added to the original buildings. The great thirteenth-century tower at Chepstow (Marten’s tower) was flooded with light in a similar fashion.

Raglan’s fifteenth-century hall, with its sixteenth-century windows.

At Raglan, William Somerset’s principal concern was his rather dingy great hall – one of the oldest parts of the castle. When he rebuilt its eastern wall, he provided the main body of the room with three large windows, while at the far end he treated himself to a grand oriel window (a window which projects from a building), better to illuminate his guests at dinnertime.

Tudor aristocrats were not simply content, however, with replacement windows. The courtyard style that was gaining popularity in the sixteenth century had led to the creation of a new species of room, and the availability of better, cheaper glass only encouraged the fashion. At aristocratic residences all over the country, masons and glaziers set to work to construct long narrow corridors, typically over a hundred feet from end to end. Such rooms were called (appropriately enough) long galleries, and every self-respecting homeowner had to have one.

Castle owners looked on enviously. The architecture of a castle could occasionally extend to indulge the private whims of its noblest inhabitants; some castles, especially later ones, were provided with private chambers, parlours and gardens. On the whole, however, castle architecture was predominantly functional. Halls were for dining and entertaining, kitchens for cooking, bedrooms for sleeping. The invention of long galleries suddenly raised the stakes in terms of frivolous opulence.

There was no fundamental need for a long gallery – it was not a covered walkway to link two other rooms; no one would sleep or dine in one; it did not, like the chapel, bring you closer to God; and it was certainly not provided with toilets. A long gallery, in the words of Roger North, a seventeenth-century authority on the subject, was ‘for no other use but pastime and leisure’. Its point was recreation. In North’s opinion, the idea had originated in Italy, where sophisticated members of society would pass their time in conversation while wandering along outdoor colonnades (columned walkways). Such architecture was fine for the villa-owning elite of southern Europe, but England was far too chilly for such al fresco chats. The obvious solution was to bring an equivalent amount of space indoors, and the long gallery was the result. It provided an interior area where genteel ladies could take a stroll without fear of catching cold. Gentlemen who needed to brush up on their fencing could repair to the gallery if rain stopped play outside. Both groups could convene in the gallery in order to rehearse their dance moves. But one did not need a specific reason; it was simply the nicest possible room for enjoyment and relaxation – a place to sit and while away the time, to make pleasant conversation, and to exhibit the trappings of wealth and taste. By the end of the sixteenth century, such was the popularity of galleries that people had even started to hang pictures in them.

Fitting a gallery inside a castle was no mean feat, but that of course did not stop fashion-conscious castle owners from trying. We have already seen how Danzig Willie’s designer struggled to squeeze one inside Craigievar, in spite of the overriding importance of making the castle tall and slender. The result just about works, but its position high up on the castle’s fifth floor would not have impressed gallery connoisseur Roger North. For him a gallery had to be down low, ideally on the first floor – off the ground, but easy to access. ‘Higher than the next floor it must not be, for such as are in garrets, as I have often seen, are useless, because none will purchase the use of them with paines of mounting.’ When you climb the stairs to the gallery at Craigievar, you can see what he means – the ascent in itself is exercise enough. Willie’s descendants evidently agreed with North’s estimation that it was ‘irksome to think of climbing so high’; the gallery was later converted to servants’ quarters.

William Somerset, faced with the challenge of adding a gallery to Raglan, managed to pull it off with considerably more panache, though the position of his gallery on the second floor would still have irked Roger North. He might, however, have been tempted up the stairs by the sheer scale of Somerset’s gallery. It stretched over the roof of the existing chapel, screens passage and buttery, and a brand new section of castle allowed it to extend further still; from end to end it measured 126 feet. North might also have been placated by the quality, both of the interior fittings and the spectacular views from the far end, where the gallery concluded with a grand set of windows looking out across the hills to the north. This magnificent room, however, did not even survive until North’s day; it is one of the most comprehensively ruined places in the castle. A few broken pieces of the great north window, and one half of a fine Renaissance fireplace, are all that remain of what was once Raglan’s most glorious room. However, some idea of its vanished splendour can be gained from contemporary equivalents. The gallery at Haddon Hall in Derbyshire, for example, if hung with paintings, would look very similar to the one that graced Raglan.

William Somerset’s additions to Raglan were not confined to the infrastructure of the castle. He also began a redevelopment of the grounds and gardens that was continued by his son and grandson, transforming his home from a castle into a pleasure palace. By the time we finally catch up with Henry Somerset, Marquis of Worcester, who inherited his father’s estate in 1628, the castle was, in the words of a contemporary, ‘accounted one of the fairest buildings in England’. The moat about the great tower had been ringed with a walkway, complete with niches containing the busts of Roman emperors. From the water rose a great fountain, its plume leaping to the same height as the castle walls. To the west lay a bowling green, admired for its situation and fine views. Beyond lay gardens and meadows, ‘fair built with summer houses, delightful walks, and ponds’. Into the distance stretched ‘orchards planted with fruit trees, parks thick planted with oaks and richly stocked with deer’.

No one arriving at Raglan in 1640 would have been in any doubt that they were in for a good time. The marquis of Worcester, with an income of £24,000, was accounted one of the richest individuals in the kingdom. His household extended to some five hundred persons; besides him and his large family, there were the steward, the comptroller, and the cook; the master of arms and the master of hounds; the wardrober and the secretary; brewers, bakers, and bailiffs; footmen, grooms, ushers, and doormen; chaplains, foresters and falconers; waiters, parkers and pages.

We also have some sense of what the marquis of Worcester was like at this time, thanks to one of his chaplains, Dr Thomas Bailey. Later in life, Bailey collected a number of his former master’s favourite stories and reminiscences, and published them under the rather misleading title Wittie Apophthegmes. Few are genuinely clever or funny – for the most part they are the self-indulgent tales of an old man, doubtless much improved by constant retelling. Nevertheless, Bailey claimed to have compiled them with ‘exactness and choice’, and they provide us with a portrait of a kindly, good-natured man, with a nice line in self-deprecating humour, and much liked by his family and household.

For over two hundred years, the marquis and his family had lived at Raglan castle, making it bigger and better with each year that passed – more opulent, more brilliant, more lavish. They could afford to do so because England was a peaceful place. The biggest danger to the marquis was gout; according to Dr Bailey, he was more than partial to a drop of claret. (‘Give it to me, in spite of all physicians and their books,’ he once quipped. ‘It never shall be said I forsook my friend to pleasure my enemy.’)

But the days of small talk in long galleries were drawing to a close. For the first time in its history, Raglan was going to experience war. It only remained to be seen whether the marquis and his ancestors, by customizing their castle, had compromised its defences.

The war was the English Civil War, or as some historians more appropriately call it, ‘The Wars of the Three Kingdoms’. To say what sparked the conflagration is difficult. A complicated mixture of causes combined to bring society to its knees in the 1640s. Some were long-term, deep-rooted problems that had existed for many decades; others were catastrophes brought about by particular individuals and specific events at the time.

Certainly one of the major causes was religion. The three kingdoms had been moving in different directions for a hundred years since the Reformation. Ireland, although it had been settled by a powerful minority of Protestants, remained a Catholic country. Scotland, by contrast, had become fiercely Protestant, having adopted an uncompromising form of worship known as Presbyterianism. It was England, however, that had ended up with the strangest arrangement of all. The Anglican Church was a curious blend of contradictory positions: a lot of the doctrine was Protestant, but the Church itself was still governed along traditional Catholic lines. Most of the population in England were regular attendees of Anglican services, some of them zealously so. There remained, however, a small but powerful Catholic minority who were not. They tended to be aristocrats, who had both the chapels in which to practise their religion privately, and the money to pay the fines that the government imposed for non-attendance at Protestant services.

The marquis of Worcester was one such Catholic aristocrat. In his chapel at Raglan (of which very little remains) he would have continued to listen to mass surrounded by gold and silver plate, and the icons and crucifixes that many of his fellow countrymen would have considered idolatrous. But despite being a member of a small religious minority, penalized if not persecuted, the marquis himself does not appear to have been a zealot. He was a godly man, certainly; Dr Bailey recalled that in all the years he spent in the marquis’s household, he ‘never saw a man drunk, nor heard an oath amongst any of the servants… very rare it was to see a better ordered family’.

But the marquis could not see much point in arguing about religion.

‘Men are often carried by the force of their words further asunder than their question was at first,’ he once said. ‘Like two ships going out of the same haven, their journeys’ end is many times whole countries distant.’

This tolerant attitude was no mere pose; the marquis applied his philosophy when recruiting his domestic staff.

‘What was most wonderful,’ Bailey recalled, was ‘half of them being Protestants and half Papists, yet never were at variance in point of religion.’

Under the marquis’s roof at Raglan, Protestant and Catholic worked side by side, with the marquis – genial, tolerant and wise – presiding over all like a good father.

If only as much could have been said for his king. Charles I, son of James I (James VI of Scotland) had come to the throne after his father’s death in 1628. A silly and stubborn man by nature, Charles contrived to make himself even more unpopular by his stance on matters of religion. The king and his court hankered after bells and smells in their church services, despite the fact that many Protestants saw this as Catholicism creeping in by the back door. Charles had also further compounded his error in the opinion of his subjects by choosing to take a Catholic as his queen.

None of this would have mattered quite as much had the king not also had a very inflated sense of his own importance and rectitude. Whereas the Marquis of Worcester appears to have been tolerant and wise, Charles was dogmatic, headstrong and foolish. In 1637, in a misguided attempt to bring unity to his three kingdoms, the king tried to force his Scottish subjects to use the new English Prayer Book. The staunchly Presbyterian Scots, as the more prescient of the Charles’ advisers had forecast, rose in rebellion.

Telling his Scottish subjects what to do would have been a lot easier for Charles had he been listening to his English ones; unfortunately he had not. By the time the king was ready to get to grips with the Scottish crisis in 1640 there had been no Parliament in England for eleven years. Charles had preferred to govern the country as he saw fit, raising money by arbitrary methods of dubious legality. Lack of funds to deal with Scotland, however, left him with no choice but to summon Parliament, and this unleashed a storm of complaints against his rule; MPs refused to co-operate over the Scottish business unless the king first addressed their long-nurtured grievances. Charles refused, jammed his fingers in his ears and tried to sort out the mess himself; but things just got messier.

In October 1641, the king’s Catholic subjects in Ireland rebelled, and many people in England regarded this new rising as a Popish plot engineered by Charles. Events finally came to a head at the end of the year, when MPs in England presented their complaints to the king in a document they called the Grand Remonstrance. Charles, however, was not about to start listening at this late stage. He tried instead to arrest his leading parliamentary critics – but failed dismally. By the time the blundering monarch and his troops arrived in Westminster, the individuals in question were long gone. But the cat was now out of the bag. Charles stood exposed as a king who had no respect for law or Parliament; a tyrant who would use force against his own subjects. As the king hurriedly gathered up his family and left London under cover of darkness, Royalists were already rallying to his aid. Parliament, meanwhile, began to organize itself to fight for its privileges. The slide towards war had begun.

For the next three years, Parliamentarians (or, disparagingly, ‘Roundheads’), slugged it out with Royalists (‘Cavaliers’), but neither side managed to achieve a decisive victory. Broadly, London and the South-East fought for Parliament, while the North and West of England backed the king; but this simple analysis disguises the complexity of the conflict. The reality was a patchwork of allegiances, shaped and distorted by religious beliefs, regional rivalries and, ultimately, whether individuals put loyalty to the Crown above liberty and consent.

Commanders on both sides struggled to transcend these difficulties as well as their own personal antagonisms. At the start of 1645, Parliament responded by creating a new national army – the so-called ‘New Model Army’. The Royalists, in an ebullient mood, misinterpreted their enemies’ decision to reorganize as a sign of weakness. By the middle of the year, each side was confident that it could beat the other in battle. When they met at Naseby (Northamptonshire) on 14 June, it proved to be the most decisive battle of the war – the turning point after three long years of fighting. Outnumbered and outgeneralled by the Roundheads, the Royalist divisions surrendered. As the king and the remnant of his army beat a retreat, they were left reflecting on the loss of four and a half thousand men, eight thousand weapons and all their great guns. From Naseby they headed west, deep into the Royalist heartlands of south Wales. Late in the day on 3 July, King Charles arrived at Raglan Castle.

At Raglan, Charles knew he was guaranteed a warm welcome. The Marquis of Worcester might not have been an arch-Catholic, but he was definitely an arch-Royalist. In the three years since the outbreak of hostilities he had poured nearly a million pounds into Charles’ war effort – more money than any other individual. Immediately after his arrival, in his hour of greatest need, the king appealed for more cash, and rather brazenly at that. Dr Bailey relates how the king demanded access to the castle’s great tower, believing that his principal backer was still keeping some gold in reserve in the basement (he wasn’t). It didn’t matter, however, how rude or foolish Charles appeared to be (from Bailey’s reports of the king’s behaviour, the marquis had ample justification for being offended on several scores). For men like Henry Somerset, supporting the king was a matter of principle. Kings were appointed by God, and loyalty to them was absolutely non-negotiable. The marquis therefore bailed the king out again with such money as he had remaining, and permitted Charles and his army to reside at Raglan for three weeks. The only thing the marquis had not done up to this point was fight for the king in person; as a man in his mid-sixties, plagued by gout, he was unlikely to be found charging into battle. His opportunity to prove himself, however, was about to arrive: the battle was now coming to the marquis.

The history of the Civil War is normally recounted as a series of battles: the quiet fields of Edgehill, Marston Moor, and Naseby are all familiar to us because of the bloody mayhem of three and half centuries ago. As in the Middle Ages, however, so too in the seventeenth century: battles were actually the exception. Throughout the Civil War, the most common form of military encounter was the siege. Before the battle of Naseby, and apart from the major engagements mentioned above, the war had been conducted as a series of sieges by small local armies. After Naseby, the fighting once again took this form. The New Model Army split into smaller contingents and set about flushing out Royalist resistance, especially in the west of England.

This was bad news for Royalists who had invested their money in luxurious but undefended mansions. In a sad echo of the Hardwick Hall rhyme, one Irish homeowner expressed the general feeling of aristocrats everywhere. ‘My house I built for peace,’ he wrote, ‘having more windows than walls.’ In such circumstances, castle owners did rather better. At Sherborne in Dorset, the local Royalist garrison put up a spirited defence, but even so the castle surrendered after only two weeks, battered into submission by Parliamentarian cannon.

Successful defence, however, required not just strong walls but strong wills. The castle at Bristol, where the walls once stood seventeen feet thick, was expected to hold out no matter what. In addition to its mighty defences and lofty position, the castle was under the command of Prince Rupert, the king’s nephew. But when the New Model Army attacked Bristol on the night of 10 September, the expensive new defences that ringed the city proved worthless. With the town itself overwhelmed and the castle surrounded, Rupert decided that further resistance was pointless. By the end of the day he had surrendered.

Charles, who was at Raglan organizing troops in order to relieve Bristol, received the news of his nephew’s capitulation with utter disbelief. The town was his last toehold in western England; with it went any hope of landing extra troops from overseas. The odds were becoming impossible, as many of the king’s supporters began to realize. As Charles slipped away from Raglan back to his temporary capital in Oxford, other Royalists started to surrender, sensing that all was lost. In October, the garrisons in the castles of Chepstow and Monmouth (both of which belonged to the Marquis of Worcester) submitted to their enemies.

This was a war, however, where the fighting was motivated not by realpolitik but by real conviction. There were some who, in spite of the odds, would rather fight on than surrender. The Marquis of Worcester was one such man. His other castles may have fallen; the king may have left him to his fate; the chances of success might be minuscule; but the marquis prepared to make his last stand.

The best preserved Civil War earthwork in Britain, Queen’s Sconce near Newark, has diamond-shaped bastions on each corner

This was not just a matter of steeling himself and his family for the inevitable. Preparation for war in Britain at this time had become an arduous and time-consuming affair. Since the outbreak of the Civil War, both Roundheads and Cavaliers had been trying desperately to catch up with the military advances that had been taking place in Europe for the past hundred years. While England had enjoyed domestic peace during the sixteenth century, in Europe religious wars had raged. Across the Continent soldiers and civilians, men and women, young and old had died in their tens of thousands. City authorities and rich individuals in France, Germany, Italy and elsewhere had invested heavily in their own protection, in some cases spending up to half their annual budgets on the upkeep of their defences. These new fortifications were very different to the tall, crenellated walls that had been built in the Middle Ages. The advent of cannon had led to a radical rethink. Walls were no longer built tall, but massively thick and squat. For the most part they were built of earth, and only revetted (reinforced) with stone, which enabled them to absorb cannon shot without cracking. Battlements had become useless (a single shot from even a small bombard could blow them away), and so they disappeared. Instead, defenders protected their walls by building bastions – diamond-shaped platforms of earth designed to carry cannon. They were thrust forward from the walls, in order to give covering fire along the length of the defences, as well as outwards in the direction of an approaching enemy.

Defences like this were unknown in Britain (only the border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed had anything even remotely comparable). At the outbreak of war, the country’s defences were hopelessly outdated. Across all three kingdoms, and especially in England, towns and castles had to be brought up to speed rapidly. The only solace for defenders was that artillery in Britain also lagged behind that of Europe, and nobody was experienced in the arts of siege warfare. Both Royalists and Parliamentarians recruited experts from the Continent to advise on both the conduct of sieges and the construction of defences. Huge new earthworks went up around cities like London, Colchester, Oxford and Exeter.

Having decided to stick it out and fight, the Marquis of Worcester was faced with exactly this task – converting his stately castle at Raglan into a military stronghold. Exact details as to how and when he carried out this process are lacking. We know that he had maintained a Royalist garrison in the castle since the start of the war. One contemporary put the number of infantry at three hundred men; another suggested that the total number of people inside the castle was eight hundred, but indicated that this figure included members of the marquis’s own household. The garrison was certainly large, and the precautions they took were correspondingly extensive. Inside, the castle was knocked around and modified. With nowhere to grind gunpowder for their twenty cannon, the Royalist soldiers converted the basement of the closet tower into a powder mill: the doorway has apparently been widened to enable barrels of gunpowder to be carried in and out. More importantly, the soldiers began to construct a ring of earthen defences around the castle. They may have started at an early date, but the context of certain comments made by Dr Bailey suggests that work was still being carried out at the time of the king’s visit in 1645. One of the bastion towers they built to the south of the castle has survived, though its contours have been much reduced by erosion (its shape can be best appreciated from the top of the great tower). From what survives, the completed defences are reckoned to have been vast, extending outwards from the walls by several hundred feet. Describing the stables and barns constructed for the garrison, an eye-witness thought them ‘built like a small town’.

The marquis, therefore, had taken every possible precaution: the castle had been customized, the earthworks constructed; the cannon had been rolled into place on top of the new bastion towers, the smaller artillery pieces mounted on top of the castle walls. All he and his household could do was sit and wait for the inevitable. An anxious Christmas came and went, with no sign of trouble. In the New Year, however, they sensed the net about them drawing tighter. In February, Cardiff fell to the Roundheads. By the spring, Parliamentary forces were beginning to mass in Monmouthshire. Finally, at the start of the summer, the inevitable arrived in the shape of Parliament’s Colonel Thomas Morgan, who drew up one and a half thousand troops to the east of Raglan. On 3 June he sent a letter to the marquis, written in the typically deferential tone of the times. Slightly abridged and simplified, it read:

Sir, I am commanded… to summon you to surrender unto me… the castle of Raglan, with all the arms, artillery, ammunition and… military provisions therein. You have no reason to hold [it], being out of all hopes of relief – all or most of the king’s garrisons are surrendered, and Raglan is one of the last. If you refuse to surrender it upon these summons, the country will consider you a disturber of the peace of this kingdom, and deprive yourself and those with you from the honourable conditions which you may now receive.

The marquis responded with a refusal – equally polite but equally uncompromising.

‘We must here,’ he concluded his letter, ‘to the last man, sell our lives as dear as we can; and this not out of obstinacy or any ill affection, but merely to preserve that honour that I desire should attend me with death. And God assist them that are in the right.’

The siege of Raglan had begun. The first task facing Morgan’s troops was to look to their own protection. To this end, they began building earthworks and digging trenches just as their Royalist opponents had done. Like trenches in the First World War, the two lines ended up very close to each other; Morgan described how he had brought his approaches to within pistol shot of the enemy lines. The Colonel had with him a skilled engineer, one Captain John Hooper, who had recently scored a great success in defeating the Royalist castle at Banbury. Hooper set about building platforms on which to mount the Parliamentary cannon; their faint outline can still be seen in the fields to the east of the castle. Soon the Roundhead gunners were in position and ready to begin their bombardment.

The barrage, when it began, was relentless. The Roundheads pounded the castle with up to sixty shot a day. The noise was deafening, the stench from the guns sickening. Once they had found their range, Morgan’s gunners were easily able to destroy the tops of the castle towers, and with them the lighter Royalist guns that had been placed there. The battlements at Raglan were only eight inches thick, and quickly crumbled under the assault. The Parliamentarians began to concentrate their fire on the larger guns around the perimeter, and also on their main objective: blowing a breach in the castle walls.

The walls, however, held out. According to a contemporary witness, ‘the [great] tower itself repulsed bullets of 18 to 20lb weight, hardly receiving the least impression.’ The walls of the rest of the castle proved equally defiant. Along the eastern face of the castle, the damage caused by the Parliamentary artillery is still very evident – the walls are chipped and battered, and a number of cannon balls have been found embedded in them. But the medieval masonry neither cracked nor collapsed under the barrage. To judge from the above comments on the size of the shot, it would seem that Morgan’s guns were simply not big enough. A gun firing shots of eighteen to twenty pounds would have been a culverin. This was a fairly impressive piece of equipment, weighing in at around five thousand pounds and measuring thirteen feet from breach to barrel. It could not, however, smash through stonework. For that, Morgan would have needed larger guns – demi-cannon, or whole-cannon. Capable of firing balls of up to eighty pounds in weight, these were a convincing answer to even the stoutest stone walls. Morgan appears not to have had them – at least, not at the outset. The problem with cannon was getting them where you wanted them in the first place. Whereas a culverin could be shifted by a team of twenty horses, a single cannon would have required two or three times as many beasts to get it moving. Even with such large trains, the biggest siege guns could only be moved a few miles a day. Trundling them along muddy tracks took weeks on end and, as such, was prohibitively expensive. Both sides were reluctant to commit cannon to the fray unless there seemed to be absolutely no alternative.

Morgan did, in fact, have other options open to him, but they were extremely tedious. While his gunners could continue to try and destroy their enemy’s artillery, his troops could hope to pick off individual defenders by using muskets. Muskets had been around for some time (about a hundred years) and had proved effective in battle, where they could be massed together and fired in volleys. In a siege situation, however, they were less useful, not having the accuracy required for long-distance sniping. Although you would be extremely lucky if you survived a shot from a musket, you would have to be exceedingly unlucky to get hit by one in the first place.

On one occasion during the siege of Raglan, the Marquis of Worcester enjoyed just such mixed fortunes. One evening after dinner, he and his dining companions had withdrawn into his private parlour beyond the great hall – a handsome room, ‘noted for its inlaid wainscotting and curious carved figures, as well as for… a large and fair compass window on the south side’. The redoubtable Dr Bailey, who (as ever) was there to witness events, described what happened next. As the marquis was about to entertain the assembled company with one of his pleasant after-dinner discourses, there was a distant crack, a whizz, and a sudden shattering of glass. A musket ball came crashing through the ornamental window, glanced off a little marble pillar, and struck the marquis on the side of the head. As the flattened bullet dropped to the table with a gentle thud, some of the ladies present fainted from the shock. The marquis, however, saw a golden opportunity for the kind of witty apophthegm that later enabled Bailey to dine out for decades.

‘Gentlemen,’ he said, turning the musket ball in his fingers, ‘those who had a mind to flatter me were wont to tell me that I had a good head-piece in my younger days; but if I do not flatter myself, I think I have a good head-piece in my old age – or else it would not have been musket-proof.’

Joking aside, the marquis must have realized he had had a lucky escape. By this stage, moreover, he can have had little else to joke about. The loss of his great ornamental window was just the latest in a long line of disasters to befall his beautiful castle. If he had dared to peek over the parapets, he would have hardly recognized the scene before him. Where there had once been ornamental gardens, orchards and ponds, there was now a war zone – a no-man’s-land where every tree had been torn down and every building destroyed. The Royalist situation was becoming desperate, and five weeks into the siege, on 12 July, the garrison attempted to break out; four hundred infantry and eighty cavalrymen poured over the defences to engage Morgan’s troops. Within half an hour, however, it was all over: the Royalists were beaten back, having sustained heavy losses.

But if the Royalists could not break out, the Roundheads could not break in. Despite the successful defeat of the sortie and the destruction his guns had wreaked on the castle, Colonel Morgan was still no closer to ending the siege. All he could do was keep tightening his grip, and order Captain Hooper to keep driving forward his trenches.

Meanwhile, events elsewhere were shaping Raglan’s fate. In May 1646, even before the siege had begun, Charles I had slipped out of his headquarters at Oxford and travelled in secret to Newark, where he handed himself over to a waiting Scottish Army. It was a desperate move, choosing what he considered to be the lesser of two evils and hoping to divide his enemies. For the Royalist troops who remained in Oxford, however, it was the beginning of the end. Negotiations began almost immediately, and within a few weeks it was all over. Having been besieged and blockaded for years, the exhausted city finally surrendered on 25 June.

The consequences of Oxford’s fell were first felt at Raglan two weeks later, when Parliament’s Major-General Skippon and Colonel Herbert arrived outside the castle with two thousand extra men. They arrived the day after the garrison had attempted to break out of the castle, and their presence put paid to any further thoughts of flight on the part of the Royalists. Joshua Sprigge, a chaplain who had arrived with the new troops, noted the scales were beginning to tip against the defenders.

‘The enemy,’ he wrote, ‘was reduced to more caution, and taught to lie closer.’

It was not Skippon or Herbert, however, who ended the siege, but two new characters who arrived at the start of August. The first was Sir Thomas Fairfax. A man of thirty-four years, Fairfax had cut his teeth fighting in the Netherlands, and made his reputation in the North of England during the early stages of the war. Although by no means a striking figure – he suffered from poor general health, and his physical sufferings had been compounded by two separate musket wounds – Fairfax demonstrated both skill as a military commander and a refreshing lack of egotism. At the start of 1645 he had been the natural choice as leader of the New Model Army. At Oxford, he had managed to persuade the Royalists to submit without a fight, and had avoided having to fire his great guns into the city. The ancient colleges had been saved, and Fairfax had taken the trouble to post a guard around the Bodleian Library in order to stop it being sacked. He now hoped to bring the siege of Raglan to a similarly bloodless conclusion.

By the time Fairfax arrived at Raglan on 7 August, it was all but the last garrison in England still holding out for the king. The fall of Oxford had been the signal for those few remaining Royalist strongholds to surrender. Only the tiny Henrician fort at Pendennis in Cornwall, strengthened by massive Civil War earthworks, was putting up a resistance comparable with Raglan’s. As Joshua Sprigge poetically put it, ‘many other garrisons that attended [Oxford’s] fate fell with it, even like ripe fruit, with an easy touch; but the two garrisons of Raglan and Pendennis, like winter fruit, hung long on.’

The garrison at Raglan, however, knew nothing of distant Pendennis. When Fairfax wrote to the marquis shortly after his arrival, he stretched the truth in order to emphasize the hopelessness of the old man’s situation.

‘Raglan only obstructs the kingdom’s universal peace’, he told him, before proceeding to pile on further pressure. He had come into Monmouthshire ‘with such a strength as I may not doubt’, and was now offering the marquis a last chance to surrender on favourable terms. If, however, the marquis delayed or refused, ‘such terms… cannot be hereafter expected’.

But the marquis continued to play the same game as before. In his letter back to Fairfax, he referred to the castle as his ‘house’, and added that (having lost both Chepstow and Monmouth) Raglan was ‘the only house now in my possession to cover my head in’. This was not a mere word game, or the sentimental blubbering of a foolish old man. The marquis was choosing to make a point about personal property and his inalienable rights as a landowner that had been a familiar theme of Royalist propaganda throughout the war. Concluding his letter, he referred to his ‘house’ for a final time, and wondered aloud how, ‘by law or conscience I should be forced out of it’.

Fairfax, exasperated, sent back a testy reply. ‘For that distinction which your lordship is pleased to make [i.e. between castle and house]; it is your house. If it had not been formed into a garrison, I should have not have troubled your lordship with a summons; and were it dis-garrisoned, neither you, nor your house should receive any disquiet from me!’

But Fairfax knew that he did not have to waste time with the marquis debating the legal merits of their respective positions. Even as he had drawn up his forces at Raglan, another character had appeared, and one with a far bloodier reputation than the general. This was a lady, no less, but one whose name struck fear into the hearts of grizzled soldiers. Roaring Meg had come to Raglan.

Roaring Meg.

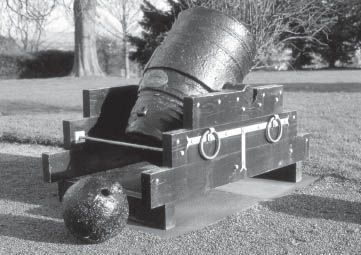

Meg was a mortar piece – a squat metal tub measuring just four feet from end to end, but nonetheless the most terrifying weapon imaginable in the seventeenth century. She was a gun, but not intended, like a conventional cannon, to smash through walls. Mortars like Meg were designed to lob their missiles clean over the defences of a town or castle, right into the heart of the enemy camp. These missiles, furthermore, were not the solid iron balls fired by cannon, but large hollow grenades, twelve inches across and two hundred pounds in weight. Typically made of copper (or a similarly brittle metal), the grenade was packed with gunpowder, and lit by a fuse before being launched towards its target. When the powder ignited, the grenade exploded, sending shrapnel flying in all directions, killing or maiming everything within a wide radius.

The mortar was, in short, an anti-personnel weapon, intended to destroy human life rather than wear down defences. Of course, a well-aimed shot weighing two hundred pounds could rip right through the roof of a building, and the explosive force of a grenade could easily start a fire. But they were not always successful, or even reliable weapons. A grenade was, in essence, a very crude type of shell – one without a detonator. It therefore required great skill on the part of the gunner to judge not only how far to fire it, but also how long to make the fuse. Too short and it would explode in mid-flight; too late and it might give the defenders the chance to render it harmless. There is a famous example of how, during the siege of Gloucester, a quick-thinking woman extinguished the fuse of a mortar grenade by throwing a bucket of water over it.

Above all, however, mortars could be relied upon to produce fear and panic among your opponents. During the siege of Lathom House in Lancashire in 1644, one of the defenders indicated the terror that a falling grenade could provoke.

‘Little ladies had stomach to digest cannon,’ he wrote, ‘but the stoutest soldiers had no heart for this… the mortar piece had frightened ’em from meat and sleep.’

From an attacker’s point of view, mortars were satisfyingly effective. Parliamentarian troops trying to break Banbury castle in 1646 reported screams every time the mortar was fired.

When Roaring Meg arrived at Raglan in August 1646, she was still only a few months old, having been specially cast earlier in the year for the purpose of defeating the Royalist garrison at Goodrich Castle. The young lady came with powerful friends. Escorted by Colonel John Birch, Meg rolled up with five of her sister-pieces, as well as all the conventional cannon that Parliament was able to spare. In terms of the mortars, at least, this was the greatest concentration of firepower so far deployed in the Civil War. Captain Hooper, who was still busy digging his way towards the Royalist lines, now began to construct platforms for the new weapons sixty yards from the castle’s defences.

As the marquis of Worcester watched Roaring Meg and the other mortars being rolled into position, he knew he was caught between a rock and a hard place. The level of danger had suddenly become far, far greater. No longer could he hide behind his ancestral walls; if the mortars were fired, there was a good chance that he or a member of his family would be killed. By the same token, surrender was not a tempting prospect. Who knows what a vindictive Parliament might do to him? As he confessed in a letter to Fairfax, the prospect of surrender ‘doth a little affright me’.

Fairfax, sensing the old man’s desperate dilemma, hammered his advantage home. Come to terms, he urged.

‘If you stand it out to the last extremity,’ he wrote to the marquis, ‘[you risk] your person, those of your family (which I presume are dear to you), and the spoil of the castle.’

Fairfax also chose to invoke the memory of another marquis who had defied Parliament to the bitter end.

‘Your Lordship has no reason to expect any better than the Marquis of Winchester received. He made good Basing House to the last, narrowly escaped with his own life, lost his friends, subjected those that escaped to great frights, and hazarded his house and estate to utter ruin, and himself to the extremity of justice.’

At the same time, Fairfax reassured the marquis that he would receive fair treatment at Parliament’s hands. ‘That what I grant,’ he promised, ‘shall be made good.’

And so, after more than two months besieged in his castle, the marquis decided that it was time to surrender. Over the weekend of 15–16 August, negotiators thrashed out the terms of the cease-fire, and on Monday a deal was struck. In two days’ time, it was agreed, the Royalist troops would march out of Raglan castle, unmolested by their opponents, and disband. Certain individuals, including the marquis himself, were exempted from this pardon; and when, on the eve of the surrender, the marquis presented the terms to his men, they pledged to keep on fighting. Their master’s mind, however, was made up. Like Jonah, he said, he would be cast overboard rather than see them all perish. Accordingly, the next morning, the Royalist garrison marched out of Raglan, with ‘colours flying, drums beating, [and] trumpets sounding’, just as the negotiators had agreed.

Both the marquis and Fairfax had good reason to be happy with the conclusion. For Fairfax, it was the bloodless outcome he had hoped for – once again, he had achieved victory without needless expenditure, either of men or of money. The marquis also had reason to be grateful. His castle and his household had got off lightly, even if he himself now faced an uncertain future. When the two men met that day, the marquis, true to form, was in good spirits. As the general was taking his leave, the old man made what Dr Bailey called ‘a merry petition’ on behalf of a couple of pigeons, which he had been feeding throughout the siege. Would the great general take the two young birds, as it were, under his wing? With so many hungry soldiers about, the marquis was concerned for their safety.

The only individual who was apparently less than pleased by the bloodless conclusion was Colonel Morgan. He was, after all, the one who had started the siege back in June, and since then he had endured the hardship of living under canvas and fighting in trenches for the best part of two months. Now, thanks to Fairfax’s negotiated surrender, his opportunity to heroically storm the breach had vanished. Worse still, he hadn’t even got to fire a mortar – Roaring Meg had on this occasion stayed silent. Writing to the Speaker in the House of Commons on the day the cease-fire was agreed, Morgan began, ‘After long and hard duty performed, it hath pleased God that commissioners on both sides have agreed upon articles for the surrender of the castle and garrison.’

You can hear the disappointment and the petulance in his voice when he finally adds that, ‘truly, had not this happy conclusion been made, our mortar pieces would have played very suddenly, and we were come very near with our approaches.’

* * *

With the siege and the war now over, Fairfax was treated to a celebratory dinner at Chepstow in the evening, before returning home to Bath the next day. In the meantime, the Marquis of Worcester was being transported to London, where he would shortly learn whether the general’s promises would be honoured now he was at the mercy of Parliament. In both houses, there was much debate over what should be done with the defeated Royalists and their castles. On the one hand, these were dangerous fortifications that had cost hundreds of thousands of pounds and the lives of many men to capture. Their continued existence was a temptation, an invitation even, for the king’s supporters and sympathizers to attempt to retake them. If, heaven forbid, they succeeded in doing so, then the same battles would have to be fought all over again. Even simply guarding them against attack would entail a huge commitment of manpower at a time when Parliament was trying to demobilize its armed forces. In such circumstances, the best way to prevent future trouble seemed to be to destroy castles completely. Colonel Birch certainly thought this would be the best way to deal with Goodrich Castle when he and Roaring Meg had finished battering it into submission. Writing to Parliament in order to ascertain ‘the pleasure of the house concerning the demolition or keeping of the castle’, he could not resist venturing his own opinion. ‘I humbly conceive [it] is useless, and a great burden to the country.’

On the other hand, Parliament had to consider its own security. After four years of punishing civil war, the country at large was restless, and Parliament, although victorious, was far from being universally popular. Perhaps, some MPs argued, it would be better to hang on to a few castles for safety’s sake, and keep them garrisoned, regardless of the cost. There were also Members of Parliament, especially the great landowners in the House of Lords, who sympathized with the plight of men like the marquis. Castles were, after all, homes, and the right of an individual to enjoy his property without interference from government had been one of the things that they had supposedly been fighting to protect.

In the specific case of the Marquis of Worcester, however, Parliament had already made up its mind long before the old man himself finally arrived in London. Just one week after Raglan’s fall, MPs had voted to demolish the castle and imprison its owner. The marquis was to be sent to the Tower (he was later committed to Black Rod in Covent Garden), and the remains of the castle were to be sold off ‘for the best advantage of the state’.

Destroying a castle, however, especially one as large as Raglan, was easier said than done. When demolition of the castle began in August 1646, it was carried out by teams of men with pickaxes. They began on the top of the great tower and, after a great deal of what one eye-witness called ‘tedious battering’, they managed to remove just one of the five storeys. Sending the old man himself to prison was no problem, but his castle, even in defeat, was proving to be a tough nut to crack.

They could have speeded things up by using explosives, a technique that had been tried earlier in the year at Corfe Castle in Dorset. A mighty twelfth-century keep perched high on a hill, girded by huge circuits of thirteenth-century curtain walls, Corfe had been unsuccessfully besieged several times during the course of the war. When it finally fell to the Roundheads through treachery in February 1646, Parliament wasted no time in ordering its destruction. Sappers set to work undermining some of the walls, and large quantities of gunpowder were used to break the keep and the gatehouses. But as well as being extremely dangerous, this was prohibitively expensive; and for all its advantages of speed, gunpowder left untidy results. The ragged lumps of stone that resulted could not be sold for profit, which was Parliament’s express intention at Raglan.

When, therefore, in the summer of 1647, Parliament finally came to a decision about what to do with castles in general, those who urged moderation and financial prudence won the day. A general cull was resisted, and only those fortifications that had been constructed since the outbreak of hostilities were ordered to be demolished.

By this date, members had an even greater dilemma on their hands. In order to defeat Charles I, his opponents had buried their widely differing opinions on politics and religion. Having beaten the king, these deep-seated divisions now resurfaced. Parliamentary leaders saw the opportunity to foist their religious views on the kingdom. The Army, politicized by years of continuous campaigning and smarting at attempts to disband it, rebelled against Parliament, before turning in on itself. Charles I, who had been purchased from the Scots at the start of the year, looked on with ill-concealed amusement. He was ferried around the country from place to place, a willing pawn in the game his enemies were playing against each other.

In 1648, the dispute between the different factions broke down irrevocably, and a second Civil War broke out. In a series of risings across the country, both discontented New Model Army veterans and die-hard Royalists once again seized castles and garrisoned them against Parliament. The hard-liners, it was now clear, had been right all along: they should have pulled down the castles while they had had the chance. With that chance now gone, and another major struggle ahead, those who advocated more ruthless policies gained the upper hand.

The hard-line attitude, both towards the king and the castles, was ultimately epitomized by one man: Oliver Cromwell. Although Cromwell and the Civil War are frequently referred to in the same breath, it was only at this stage in the conflict that the former East Anglian farmer began to come into his own. Driven by his views on religious liberty, Cromwell had fought in the first war with an uncompromising passion and, through his intuitive military genius, had risen to become one of the leading voices in government by the time the war was over. When trouble erupted in 1648, it was to Cromwell as much as to Fairfax that Parliament now looked for its deliverance. The fighting that year was localized but extremely fierce. Fairfax dealt with revolts in the South-East of England, at Maidstone in Kent and Colchester in Essex. Cromwell, in the meantime, had been sent into south Wales to break the rebels in Pembrokeshire, a job that took him most of the summer. In August, Cromwell marched to engage a Scottish army that had crossed the border into Lancashire, and won a resounding victory at Preston. By the start of September, the only thing that stood between Parliament and total victory was the castle of Pontefract in Yorkshire.

Pontefract was a truly impregnable fortress where, as at Raglan, the medieval defences had been massively strengthened by the addition of new earthworks. During the first Civil War it had been besieged for months on end by Parliamentarian troops who, despite being armed with cannon and mortars, were unable to take the castle by storm. When it finally fell in July 1645, it was starvation rather than bombardment that had persuaded the Royalists inside to surrender.

In May 1648, however, the king’s supporters had recovered Pontefract without a fight. It was taken by an ingenious ruse, described over half a century later by the last surviving participant, Captain Thomas Paulden, in a letter to a friend. Paulden explains how he and his fellow-conspirators first attempted to sneak into the castle under cover of darkness one night in the middle of May. They had persuaded one of the corporals in the Parliamentary garrison of the justness of their cause, and he in turn had arranged to be on guard that night.

The simple plan backfired when the Royalists approached the castle walls. ‘The corporal happened to be drunk at the appointed hour,’ said Paulden, ‘and another sentinel was placed where we intended to set our ladder.’ Inside the castle the alarm was raised, and the Royalists beat a hasty retreat.

When the Parliamentary governor heard the news, he strengthened the garrison with hundreds of extra troops, and it now seemed that taking the castle would be impossible. Then, very shortly afterwards, the Royalists received a piece of news that gave them a brilliant idea. With all the extra soldiers now in the castle, the Parliamentarians had run out of sleeping space, and had therefore sent out orders into the town for extra beds. Paulden and co. therefore decided to pose as bed-delivery men. ‘Dressed like plain countrymen and constables… but armed privately with pocket pistols and daggers’, they escorted the furniture right into the heart of the castle. Once inside, they threw off their disguises, whipped out their pistols, and imprisoned the Roundheads in the castle’s dungeon.

Like Greeks at Troy, the daring band of Royalists had pulled off the most audacious coup. They must have been overjoyed; astounded at their good fortune and delighted with their own cunning. ‘Pontefract was thought the greatest and the strongest castle in England’, said Paulden, and yet he and a handful of friends had snatched it from right under Parliament’s nose.

The Cavaliers, however, were not laughing for very long. In August the news came that their Scottish allies had been beaten. By September, the castle was surrounded by five thousand Parliamentarian troops. Finally, in November, Cromwell himself arrived at Pontefract, determined to take the castle at any cost.

Before his arrival, the siege had been under the direction, loosely speaking, of the splendidly named Sir Henry Cholmondley, a Blimpish figure who for months had been furnishing his superiors in London with rosy reports of his progress. In actual fact, Cholmondley had been so busy quarrelling with other Parliamentarian officers on how best to prosecute the siege that he had not even managed to mount an effective blockade; supplles were still finding their way to the Royalists inside the castle.

Cromwell, when he arrived at the start of November, therefore found he faced a near-impossible task. Regarding the castle itself, he echoed Paulden’s estimation of its defensive advantages.

‘The place is very well known to be one of the strongest inland garrisons in the kingdom,’ he wrote to Parliament, ‘well-watered, situated upon a rock in every part, and therefore difficult to mine. The walls are very thick and high, with strong towers, and… very difficult to access, by reason of the steepness of the graft.’

Disabusing MPs of the notion that victory was close to hand, he wrote, ‘My Lords, the castle has been victualled with 240 cattle within these three weeks, and they also gotten in salt enough for them, so that I apprehend they are victualled for a twelvemonth. The men inside are resolved to endure to the utmost extremity, expecting no mercy – as indeed they deserve none.’

Having made his assessment and stated his case, Cromwell proceeded to list the tools necessary for the job. To break Pontefract would require at least three regiments of foot, two regiments of horse, five hundred barrels of gunpowder, six good battering guns and eighteen hundred cannonballs. A couple of mortars would also be nice, he added, if Parliament could spare them.

As at Raglan, it was going to be weeks before any of these items arrived at Pontefract. In the meantime, Cromwell wrote to the Royalists and demanded their surrender. In response, their captain sent only a teasing letter – was Cromwell quite sure that he had full authority in this matter? Perhaps he ought to check with Sir Henry Cholmondley, and see what he thought? When they had sorted it out between them, could they get back in touch? Cromwell’s answer, written or otherwise, is sadly not recorded. But after two more weeks of waiting, he turned from Pontefract, and headed towards London. He had not, however, given up on his Royalist enemies: on the contrary, he was about to play his trump card.

Cromwell arrived in London on 6 December, and that evening sent Colonel Pride to purge the House of Commons of his political opponents. Now that the fighting was all but over, the Army had grown tired of Parliament’s dithering about what to do with the king. As far as Cromwell and his comrades were concerned, Charles I was a tyrant and a traitor, a king who had made war on his own people, ‘a man of blood’. Like the criminal that he clearly was, Charles was going to be tried, convicted and punished. For a man guilty of such crimes, there was only one possible punishment. On 30 January 1649, the king was led to the scaffold in Whitehall, and publicly beheaded.

By this shocking, unprecedented act, the siege of Pontefract was brought to an end. For the Royalist garrison, who by now were being pounded by cannon and mortars, the king’s death was a crushing blow to their cause. After they heard the news, they made a show of pledging their support to Charles’s son, but a few weeks later their resistance crumbled. At the start of March, negotiations for a surrender began, and by 22 March the Royalists had capitulated. Pontefract was retaken, and the second Civil War was over.

Having killed the king, Cromwell and his supporters now set out to kill the castle. No way was there going to be the kind of general reprieve that had followed the last war. Pontefract, recently the biggest thorn in the government’s side, was one of the first candidates for the chop. This was far from being an unpopular decision. As early as 24 March – just two days after the siege had ended – the cry had gone up for the castle to come down.

‘The chief news now,’ wrote one local correspondent, ‘is that the grand jury of York, the judge… and almost all this county are petitioning to get this castle pulled down.’

Parliament concurred in this opinion – with the Commons shorn of its more hesitant members in December, and the House of Lords recently abolished as ‘useless’, power was in the hands of uncompromising men. When the order was given that Pontefract ‘be forthwith totally demolished and levelled to the ground’, this time they meant it. When you visit the castle site today, you can see how literally the commissioners and the people of south Yorkshire took the decision: hardly one stone was left standing on top of another. Pontefract, one of the mightiest royal castles in England, was reduced to a pile of rubble.

Similar severe punishments were dealt out to other castles in the wake of the king’s execution. At Belvoir, Montgomery and Nottingham, destruction took place on a scale comparable to Pontefract. Significantly, both Belvoir and Montgomery had escaped destruction in 1647, when only the new works that had been added to them were destroyed.

Parliament soon found, however, that the cost of such wholesale demolition was unbearable. At Pontefract, even though the sale of the lead, stone and timber from the demolished castle had raised £1,779, the townspeople still found that the job saddled them with a debt of £145. At Belvoir and Montgomery, the government hit upon the idea of paying the owners to pull down their own castles. Since both were the property of former Royalists, who were heavily fined for supporting the king, ‘payment’ was simply a matter of reducing their fines rather than actually shelling out hard cash.

But where demolition was not self-financing, it became much harder to enforce. Local government was soon complaining about the cost of carrying out orders for total destruction, and in many places those orders were not carried out for lack of money. In other instances, a lack of expertise also created problems on the ground. There were laughable scenes at Belvoir when the Earl of Rutland had finished pulling down his castle. Parliament naturally wanted the work inspected to make sure that the job had been done properly. Unfortunately, however, the men they appointed to view the work were local gents rather than military engineers, who were forced to confess they did not know whether the castle was now indefensible or not. Faced with such difficulties, central and local government arrived at a compromise. castles in future would not be demolished but ‘slighted’. Rather than outright demolition, the authorities would be content with limited destruction that made castles untenable – left standing in places, but incapable of being defended in battle.

Slighting was the solution that was finally adopted at Raglan, and the castle as it stands today bears testimony to the terrible effectiveness of the procedure. Having tried and failed to bring down the great tower stone by stone with pickaxes, engineers opted instead for the quick fix of undermining its walls: the same technique that King John had used to devastating effect at Rochester four centuries beforehand. ‘The weight of [the tower was] propped with timber,’ said an eye-witness, ‘while two of the sides were cut through; the timber being burned, it fell down in a lump.’ There was more to slighting, however, than simply making a castle indefensible. By throwing down the walls of the homes of the nobility, walls that for centuries had symbolized the power of an aristocratic elite, the revolutionary government was making a striking visual point about its own power. No longer, it said, would individuals be allowed to defy the state (the Commonwealth, as it would soon be called) in the name of privilege. The broken towers at Kenilworth and Scarborough, Helmsley and Corfe, were witness to their owners’ impotence in the face of Parliament’s might. At Raglan, the deliberate and systematic spoliation of what had been one of the greatest, fairest and noblest buildings in the country was carried through with savage thoroughness. Every window was smashed, every fireplace ripped out, every valuable removed. The banks of the ponds and the moat, both still teeming with carp, were broken. The chapel, filled as it was with images of Popish idolatry, was singled out for special attention. Most callously, and in direct contrast to the way in which the Bodleian in Oxford had been spared, the huge library of rare books and manuscripts at Raglan, reckoned one of the most important collections in Europe, was deliberately put to the torch. What took place at Raglan was not just an act of essential demolition – it was an act of vengeance.

While the heart was being ripped out of his castle at Raglan, Henry Somerset, the Marquis of Worcester, lay dying in London. His ancestral home, he now knew, would not be passing to his heirs, as he had always imagined it must. The assurances of fair treatment made by General Fairfax had, in the end, counted for nothing. Having fought what he considered an honourable fight in defence of his faith and his king, the marquis had good cause to reflect on his shabby treatment at Parliament’s hands. By his bedside stood Dr Bailey, his chaplain, remembering the old man’s last words even as he administered the last rites.

‘Ah, Doctor,’ said the marquis, ‘I forsook life, liberty and estate… and threw myself upon their mercy; [but] if to seize all my goods, to pull down my house, and sell my estate… be merciful, what are they whose mercies are so cruel?’

Nevertheless, in spite of his appalling experience that summer, the plethoric constitution that had preserved him for seventy years still refused to desert him. Even as he stared into the abyss, the Marquis of Worcester managed one last witticism. He asked where he was to be buried, and was told that his final resting place would be the great chapel at Windsor Castle.

‘Why then,’ he quipped, ‘I shall have a better castle when I am dead than the one they took from me when alive.’

1. Both Henry Somerset and Raglan have complicated identities. Somerset was Earl of Worcester down to 2 March 1643, at which point he was promoted to the rank of marquis. For simplicity’s sake I have called him ‘the marquis’ throughout. Monmouthshire was considered part of Wales when Raglan was built in the fifteenth century, but its status became ambiguous after 1536, and it was often treated as an English county. The ambiguity persisted until 1974, when the county was absorbed into the Welsh administrative region of Gwent.