On 7 February 1469 a giostra, or joust, was held in Florence in honour of the twenty-year-old Lorenzo de’ Medici: his rite of passage into public life and a celebration of his forthcoming marriage to Clarice Orsini (a Roman bride, and at this stage an unpopular choice). He rode through the streets with his troupe of cavaliers, from the Palazzo Medici to the tourney-lists in Piazza Santa Croce. The splendour of his accoutrements goes without saying – the silks and velvets and pearls, the chased armour, the white charger given him by the King of Naples – but let us look for a moment at the banner which flutters above him, specially designed for the occasion: a ‘standard of white taffeta’. The poet Luigi Pulci describes the design on it. It was ‘decorated with a sun above and a rainbow below, and in the middle a lady standing in a meadow, wearing a robe in the antique style [drappo alessandrino] embroidered with gold and silver flowers’. In the background was ‘the trunk of a bay-tree with several withered branches and in the middle a single green branch’.59 The bay-tree (lauro) puns on ‘Lorenzo’. His father was ailing – he would be dead by the end of the year – but Lorenzo was the puissant new growth on the family tree.

Lorenzo’s standard was the work of Andrea del Verrocchio. It has long since disappeared, and was hardly one of his major works, but it speaks volumes about the bottega’s prestige at this moment of semi-princely succession. Lorenzo’s standard, we can be sure, was the best that money could buy. It also reminds us of the artists’ involvement in every visual aspect of Florentine civic life – not just in paintings and sculptures and architecture, but in the sumptuous ephemera of public pageants like the giostra. The Florentine calendar was awash with spectaculars of all sorts. There was carnival in the weeks before Lent, and the holy processions of Easter, and then the celebrations of Calendimaggio or May Day, which carried on intermittently until 24 June, the feast-day of the city’s patron saint, St John the Baptist. There were ‘lion-hunts’ in the Piazza della Signoria, and football matches in Piazza Santa Croce – calcio storico, as the game is now called: twenty-seven a side, and ‘played less with the feet than the fists’ – and there was the annual horse-race, the Palio, intensely contested between the city’s gonfaloni. The race-track crossed the city from the Porta a Prato to the Porta alla Croce; the Vacca tolled three times for the start; the winner’s trophy was the eponymous palio, a talismanic piece of crimson silk trimmed with fur and gold tassels. A famous jockey of the day was Gostanzo Landucci, brother of the diarist Luca.60

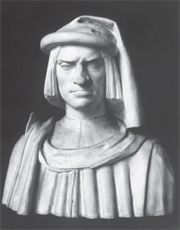

Portrait bust of Lorenzo de’ Medici by Verrocchio.

The Medici understood the therapy of public festivities, and under Lorenzo these spectacles were much encouraged. It might be muttered up on ‘the Hill’ that this was to distract the people while their liberties were being eroded by Medici cronyism and vote-rigging, but if there was a politic element of ‘bread and circuses’, there was also Lorenzo’s genuine relish for festivity. Carnival was becoming an ever more elaborate spectacle. There were torchlit parades of decorated wagons, the ancestors of the modern carnival-float. It was traditional for these to represent the various guilds, and many of the carnival songs were profession-related – ‘The Song of the Tailors’, ‘The Song of the Oil-Makers’ and so on – but now the fashion was for more courtly classical or mythological themes. Increasingly lavish and ingenious, these festive juggernauts became a kind of triumphalist political rhetoric: they were indeed called trionfi (triumphs), recalling the victory pageants of imperial Rome, but now emphasizing the power and glory of the Medici. And, as of old, bawdy songs and catches were sung – only now the smart set was requesting such numbers as the ‘Song of the Sweetmeat-Sellers’ and the ‘Triumph of Ariadne and Bacchus’, both written by Lorenzo himself, and others by his literary friends Agnolo Poliziano and Luigi Pulci. Lorenzo’s herald, Battista del Ottonaio, was a particular expert in this genre.

The supercharged pageantry of Medici jousts and carnivals was the popular theatre of the day, and all the festive hardware that went into it – the standards, banners, costumes, masks, armours, caparisons and triumphal wagons – came out of the workshops of Verrocchio and his ilk. One does not see Leonardo as the kind of jovial extrovert who revels in the mayhem of carnival, but as theatre it transfixes him. We would surely find his face among the crowd at Lorenzo’s giostra – he had perhaps worked on the standard; he was a connoisseur of horses and horsemanship; he would later be involved in giostra entertainments in Milan. I fancy we would also find him among the crowd outside the Duomo on Easter Sunday, watching the famous scioppio del carro, an incendiary rendition of the descent of the Holy Spirit in which a cartload of fireworks, hauled up from the Porta al Prato by a team of white oxen, was set off by an artificial dove propelled along a wire strung between the Duomo and the Baptistery. There is a memory of this, perhaps, in the sketch of a mechanical bird on a wire in the Codex Atlanticus, captioned ‘bird for the comedy’. The early biographers agree that Leonardo created flying-machines of this more illusionist, theatrical sort: ‘Out of a certain material he made birds which can fly.’61

Another form of public theatre was the sacra rappresentazione, or sacred show, the Florentine equivalent of the medieval English miracle plays. These shows were performed on holy days in churches and cloisters by young boys belonging to religious foundations. They were big productions, conspicuously financed by the Medici and others. There were special effects – huge revolving discs to change the scenery; wires and pulleys to make actors fly through the air. According to Vasari, Brunelleschi invented many of the cunning devices or ingegni that made such special effects possible. At San Felice there was a performance of the Annunciation every 25 March (the Feast of the Annunciation, or Lady Day). Heaven was up among the roof-trusses, and Mary’s house was on a stage in the nave; the angel Gabriel was perilously winched down on a wooden cloud to make his announcement. Another popular rappresentazione was performed on Ascension Day at the Carmine monastery. These shows enacted the same religious scenes that the painter depicted; their groupings and gestures and tableaux vivants fed into the more subtle narrative conventions of the paintings. A visiting bishop made this connection, commenting after a performance of the Annunciation that ‘the angel Gabriel was a beautiful youth, dressed in a gown as white as snow decorated with gold, exactly as one sees heavenly angels in paintings.’ As Leonardo prepared to paint his own version of the Annunciation, these witnessed scenes were part of what he had to work with.62

Leonardo’s love of theatre takes wing later in Milan, but is grounded here in the jousts and processions and sacre rappresentazioni of Medici Florence. He is the handsome, slightly quizzical young man standing at the edge of the crowd – rapt but alert, observing and calculating, working out how it’s done.

In 1471 Verrocchio and his assistants were involved in preparations for another kind of spectacular: the state visit of the Duke of Milan. Verrocchio was commissioned by Lorenzo de’ Medici to make a helmet and suit of armour ‘in the Roman style’ as a gift for the Duke, and the studio was also called on to redecorate the guest apartments of the Palazzo Medici. This marks the first definite presence of Leonardo in the Medici ambit – as an interior decorator, no more – as well as his first contact with the Milanese court, which would become his habitat in years to come.

The visit was controversial. The old duke, Francesco Sforza, had been one of the Medici’s principal allies, but his son Galeazzo Maria Sforza, who succeeded him in 1466 in his early twenties, was a sinister and profligate young man with a reputation for appalling cruelty. According to the Milanese chronicler Bernardino Corio, ‘he did things too shameful to write down.’ Some things which did get written down (though this does not guarantee their truth) were that he ‘violated virgins and seized the wives of other men’, that he cut the hands off a man whose wife he fancied, and that he ordered a poacher to be executed by forcing him to swallow a whole hare, fur and all.63 The Medici’s enemies argued that this undesirable young duke should be ditched, and that Florence should return to its old alliance with Venice, but Lorenzo maintained that good relations with Milan were essential to Florentine prosperity. The fact that Galeazzo’s wife, Bona of Savoy, was a daughter of the King of France added a further diplomatic dimension.

The Duke’s magnificent cavalcade entered Florence on 15 March 1471. A document in the Milanese court archives entitled ‘Le liste dell’andata in Fiorenza’ gives us an idea of its size – about 800 horses in all, carrying a retinue of courtiers, chaplains, butlers, barbers, cooks, trumpeters, pipers, dog-handlers, falconers, ushers, pages, wardrobe-mistresses and footmen (among the latter one called Johanne Grande, or Big John).64 A portrait of Galeazzo by Piero del Pollaiuolo, probably painted during this visit, shows a hooked nose, a sardonic curve of the eyebrow, a small mouth, a glove held in a fastidious hand. Among the troupe was Galeazzo’s younger brother Ludovico, known for his swarthy looks as Il Moro – ‘the Moor’. Still a teenager, and still on the periphery of Milanese power-politics, he was a young man to watch. Ten years after this first glimpse of him, Leonardo would be heading north to seek his patronage.

In view of this later allegiance, the Florentine reaction to the Duke’s visit is interesting, for it suggests something that, perhaps unconsciously at this stage, attracted the young Leonardo. Machiavelli criticized the hedonism – as we would say, the ‘consumer culture’ – of young Florentines at this time, and particularly associated it with the pernicious influence of this Milanese visit:

There now appeared disorders commonly witnessed in times of peace. The young people of the city, being more independent, spent excessive sums on clothing, feasting and debauchery. Living in idleness, they wasted their time and money on gaming and women; their only interest was trying to outshine others by luxury in costume, fine speaking and wit… These unfortunate habits became even worse with the arrival of the courtiers of the Duke of Milan… If the Duke found the city already corrupted by effeminate manners worthy of courts and quite contrary to those of a republic, he left it in an even more deplorable state of corruption.65

We do not know the precise motives of Leonardo’s move to Milan in the early 1480s, but it may be that some of these ‘courtly’ qualities given such a negative spin by Machiavelli – snazzy clothes, witty banter, effeminate manners – were more congenial to him than the robustly bourgeois ethos of republican Florence.

There were sacre rappresentazioni put on in the Duke’s honour, among them a Descent of the Holy Ghost to the Apostles, performed at San Spirito, the Brunelleschi church on the Oltr’Arno. On the night of 21 March a fire broke out during the show, causing panic and considerable damage. For the preachers of Florence it was divine retribution for the decadence and opulence of the Milanese, and their feasting during Lent, but a spark of that fire glows on in Leonardo’s memory.